The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

When someone applies for a mortgage, they trust a home loan lender or mortgage broker with some of the most sensitive information they have: information about their credit, their home, and the personal details of their lives.

Unbeknownst to those prospective homeowners, they may also be sharing that information with Facebook.

The Markup tested more than 700 websites that offer loans for people looking to purchase or refinance a home, from major online brokers to lesser-known regional lenders, and found that more than 200 of them share some amount of user data with Facebook. On their sites, these companies embedded the Meta Pixel, a small piece of tracking software that shares visitors’ information with Facebook. As users filled out mortgage applications or requested quotes for mortgage rates, the pixel tracked information about their credit, veteran status, occupation, the specific homes they wanted, and more. Experts told The Markup that it might be against the law for mortgage lenders to feed this kind of information to Facebook.

The Fairway Independent Mortgage Corporation, for example, offers mortgage options across the U.S. and says it funds more than $70 billion in transactions per year, making it among the largest lenders in the country. The Markup found the company’s website using the Meta Pixel to track detailed information about visitors, including every button they clicked on a preapproval page, and the type of home that visitors were interested in. The site even tracked responses to a question about visitors’ estimated credit, asking visitors to select a numbered band from “Poor,” or less than 580, to “Excellent,” or more than 740. Clicking “I Decline” to the site’s cookie notice didn’t stop the pixel from tracking.

The pixel also sent Facebook a scrambled version of a visitor’s name and email address. Meta says these “hashed” email addresses “help protect user privacy.” But it’s simple to determine the pre-obfuscated version of the data—and Meta explicitly uses the hashed information to link other pixel data to Facebook and Instagram profiles.

See our data here

Kirby Bradley, the chief content officer for Fairway Mortgage, said in an emailed response to questions from The Markup that the company has stopped using the pixel. She said the credit estimates shared with Facebook were not scores but rather “categories made up completely by the respondent based on nothing but their feeling at the time.”

Bradley told The Markup that Fairway did not collect or transmit personally identifiable information during the time the pixel was in use but declined to detail how the company defines such information.

LendingTree lets users compare loan offers from different companies. Its website sent data to Facebook through the Meta Pixel when we filled out its mortgage search form. The data included a unique ID, as well as information on co-borrowers, bankruptcy, homeownership, and military history.

Pixel Hunt

Members of Congress Call for IRS to Investigate Tax Companies Sharing Data with Facebook

The Markup revealed the companies’ practices last year

Veterans United Home Loans, which offers loans backed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, used the Meta Pixel for its online loan calculator, telling Facebook whether visitors are homeowners and even what branch of the military they served in. The company’s site also tracked personal information, including full name and phone number, but those fields show up blank when the data goes to Facebook. It is not clear whether this is intentional, and the company did not respond to a request for comment from The Markup.

Doorway Home Loans, a Texas-based lender that offers services across the country, tracked button clicks throughout its online application process, which includes questions about citizenship and whether applicants own a home. Facebook did not receive explicit application responses, but it did receive information about which buttons applicants pressed, making it easy to infer their selections.

ZeroDown is not itself a lender but a startup that offers to buy a home on customers’ behalf through its rent-to-own program. The site sent the exact address of homes that users viewed to Facebook, attached to a unique URL, and told the social platform how far down they scrolled through individual pages. It also sent financial information including offers or what mortgage payments the potential customer could afford. If someone used the site’s chatbot for information or sent a message about a listing, the full text of their conversation was even sent to Facebook.

Local mortgage lenders used the pixel, too. Indiana-based Ruoff Mortgage logged hashed email addresses and names in an application, sending them along to Facebook. The company’s site also tracked users’ responses to questions about their veteran status and dependents and logged the value of property that visitors currently own. The Arkansas Federal Credit Union’s website sent Facebook the emails and phone numbers of visitors through the pixel, along with the fact that visitors were interested in a loan.

A spokesperson for Meta, Emil Vazquez, said in an emailed statement that the company’s system uses automated tools to filter out “potentially sensitive data it is able to detect.”

“Advertisers should not send sensitive information about people through our Business Tools. Doing so is against our policies and we educate advertisers on properly setting up Business Tools to prevent this from occurring,” the spokesperson said.

LendingTree, Veterans United, Doorway, and ZeroDown did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did Ruoff Mortgage nor the Arkansas Federal Credit Union.

Many large lenders didn’t transfer especially sensitive data through the pixel. Rocket Mortgage, the largest mortgage lender in the U.S., for example, used the tool to track where people navigated on an application but did not share any personal information they entered on forms.

Possible FTC Penalties

The online mortgage industry is valued at tens of billions of dollars globally, and it’s on track to keep taking up a greater share of the market for home loans. Digital mortgage companies offer a simple way to apply for a loan, enticing potential borrowers with simple forms and faster processing times for applications. But those businesses are also beholden to strict rules under the law about handling consumers’ financial information and could be penalized by the Federal Trade Commission for violating those rules.

Pixel Hunt

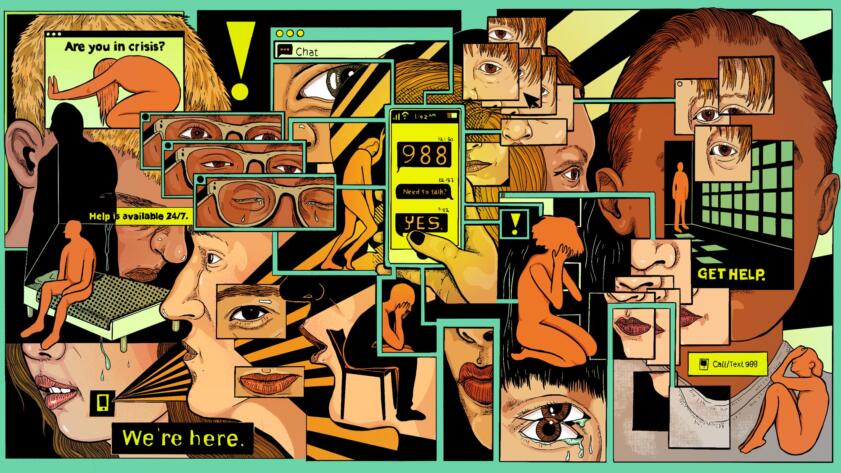

Suicide Hotlines Promise Anonymity. Dozens of Their Websites Send Sensitive Data to Facebook

The Markup found many sites tied to the national mental health crisis hotline transmitted information on visitors through the Meta Pixel

The FTC and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have the power to police financial data under the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act. The legislation is meant to secure users’ private financial information; while it applies to businesses like banks, it also covers several “non-banking financial institutions” that handle consumers’ financial data. Among the types of businesses that the FTC says are covered by the law are payday lenders, car dealerships—and mortgage brokers.

Those types of businesses are required to take specific steps to keep unauthorized users from accessing financial data. If a breach does happen, those businesses must inform the FTC promptly, or face potential fines. The businesses must also clearly inform customers about how their information is shared, and give them a chance to opt out, or risk a crackdown from regulators.

Representatives for the FTC and the CFPB declined to comment.

Natalie Loebner, a consultant and former Justice Department trial attorney who has litigated financial cases, told The Markup in an interview that mortgage companies using the pixel to share sensitive information with Facebook could violate the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act or other regulations. Loebner said it could also lead to scrutiny from regulators if the mortgage brokers failed to properly disclose how they used customer information. In its testing of sites, The Markup did not agree to data-sharing terms beyond generic cookie disclosures.

While this type of disclosure could be allowed in certain limited circumstances, Loebner said that The Markup’s reporting on the Meta Pixel suggested that regulators might want to examine how mortgage companies are also using the tool.

“I think that there’s a level of sloppiness that you’ve identified in some of the other [Markup] reporting that may give rise to concern by the FTC that it’s something they should explore more closely,” she said.

Hunting the Meta Pixel

To investigate how mortgage companies use the pixel, The Markup relied on two organizations, Home Lending Pal and the Mortgage Research Center, that maintain lists of home lenders, banks, and mortgage brokers that are registered in the national database of mortgage lenders. We also added a few other well-known online lenders, like Rocket Mortgage, to the list.

Using an automated script on Google to find each mortgage company’s associated websites, we developed a list of more than 700 domains to check. Then we ran those websites through Blacklight, a tool developed by The Markup that scans sites for tracking technology, to see which ones used the Meta Pixel. We then found the associated website for each of those domains, ending up with a list of more than 200 that were using the pixel.

The Meta Pixel is a small piece of code that quietly underpins the business of advertising on the internet. As web users click, search, browse, and shop, they’ll almost undoubtedly run into one of the millions of pages across the internet that use the code to track customers.

The idea behind the code, which Meta makes freely available, is that businesses can better target future customers by gathering information on them. If a person visits a website looking for a bathing suit, for example, the pixel can track that interaction. The owner of the website can then go to Facebook and pay to advertise on the platform to everyone who viewed that bathing suit. Maybe the business will try to show them other bathing suits on Facebook or entice them into considering a matching pair of sunglasses.

The majority of the mortgage company sites we examined didn’t track users in an especially troubling way. Many used the pixel only on their homepages, for example, and sent users to a separate page without pixels to apply for a loan. Dozens of other sites we examined had informed Facebook that a visitor had viewed a certain page but they didn’t log any information the person entered on applications. This was the case for some companies, like the widely used Credit Karma.

Several other sites we examined, like LendingTree and ZeroDown, used the pixel in slightly more invasive ways. Only a handful of sites tracked detailed personal and financial information.

Alicia Solow-Niederman, an associate professor of law at George Washington University, said that the data sharing found by The Markup is “at a minimum” legally dubious. “It certainly does not comport with what I think are reasonable consumer expectations when I tell a site my sensitive financial information,” she said.

Businesses pay Meta for the advertisements that follow users across the internet, giving companies a chance to reach more customers. Meta also reserves the right in its business tools terms of service to use the data it collects to power its advertising algorithms, which rely on massive amounts of information to build profiles on people. Facebook can then use that information to more effectively target its ads. Facebook may gather this information whether or not a person has an account on the platform.

Pixel Hunt

Facebook Watches Teens Online As They Prep for College

An investigation by The Markup found Meta’s pixel tracking students from kindergarten to college

It’s not entirely clear where this information winds up—one leak from company engineers suggested even Facebook itself can’t say for certain where the data it collects goes. The engineers wrote in a document obtained by Vice’s Motherboard in 2022 that they “do not have an adequate level of control and explainability over how our systems use data.” Sensitive data like this may be powering Facebook’s systems without humans being aware of it at all. (A spokesperson told Motherboard that the document did not accurately describe how the company handles and protects personal data.)

To better understand how pervasive the pixel is, The Markup launched the Pixel Hunt in 2022, a series of investigations dedicated to uncovering the surprising and concerning information harvested by pixels.

Since launch, the series has uncovered several instances of pixels gathering sensitive data. Among other places, we uncovered pixels on sites for federal student aid, hospitals, and suicide prevention organizations. The revelations have led to private litigation and calls from lawmakers for action.

In November 2022, we found that major tax preparation services, including H&R Block and TaxAct, told Facebook about users who were filling out their taxes. The companies sent the tech giant information on filers’ income and dependents, among other data.

The tax prep companies have faced lawsuits and regulatory scrutiny in response, and the FTC warned the businesses directly that they might be penalized if they kept doing it. In letters to the companies The Markup investigated, the FTC said it considered it “an unfair or deceptive act or practice to use tracking technologies such as pixels” in some contexts without informed user consent. The warnings said businesses could face penalties of more than $50,000 for violations.

Despite the repeated incidents, Meta has said that it doesn’t want companies that use the pixel to send sensitive financial information, like income and credit scores. The tech company has pointed out that businesses using its tools must agree through its terms of service not to send such information. Facebook also says it uses automated tools to attempt to block sensitive information from being sent, but it’s not clear in any case whether that’s happened.

In practice, despite the terms of use, businesses send this sort of data again and again. Solow-Niederman told The Markup that one problem is that regulators are overwhelmed and can’t fully enforce penalties for companies caught violating privacy regulations.

“I actually think there are people at agencies like the FTC and the CFPB who are trying their best to adapt their laws,” she said, “but they have the tools that they have and they’re so resource-constrained and deprived of the funding and staff that they need.”