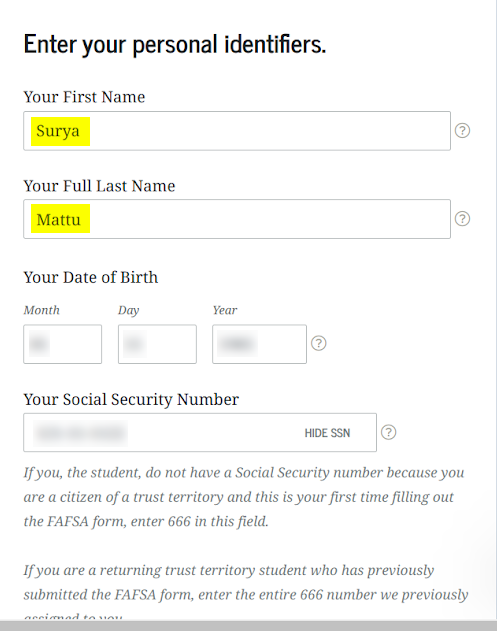

For millions of prospective college students, applying online for federal financial aid has also meant sharing personal data with Facebook, unbeknownst to them or their parents, The Markup has learned. This information has included first and last names, email addresses, and zip codes.

After The Markup questioned the U.S. Department of Education about the tracking practice, the feature that enables sharing those details with Facebook was turned off. But personal data from an unknown number of students remains in Facebook’s hands, to be used for its own purposes. According to the company’s privacy policy, it may retain this type of data for years. And the tracker remains on the website and continues to share some information about visitors with Facebook.

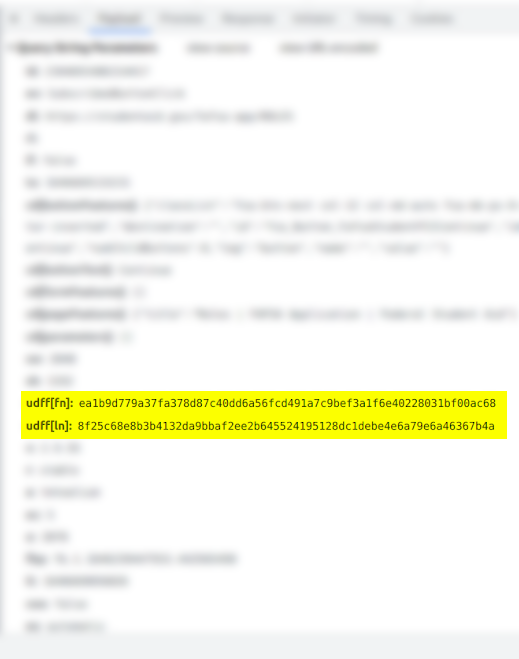

The Markup found that code embedded in the website where students fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, was automatically sending the data to Facebook. The data was being collected even if the visitor to the site did not have a Facebook account and began even before the user logged in to studentaid.gov, the site that hosts the form.

See our data here.

A spokesperson for the Department of Education initially denied that the tracking had occurred in an email to The Markup. After publication, Federal Student Aid chief operating officer Richard Cordray sent a statement to The Markup saying that, as “part of a March 22 advertising campaign,” the agency changed its tracking settings. “This inadvertently caused some StudentAid.gov user information that falls outside of FSA’s normal collection efforts, such as a user’s first and last name, to be tracked.”

But The Markup’s data shows information like a user’s first name, last name, country, phone number, and email address being sent to Facebook from the site as early as January 2022, months before the mentioned advertising campaign began.

The data sent to Facebook “was automatically anonymized and neither FSA nor Facebook used any of it for any purpose,” Cordray said in the emailed statement. “The pixel functionality in question was deactivated soon after the campaign ended as part of FSA’s typical campaign maintenance.”

The department declined to respond to follow-up questions about when the tracking was turned on or how the department could ensure the data did not make its way into Facebook’s algorithms.

Facebook has repeatedly said it blocks the collection of especially sensitive personal information. “We are in touch with [studentaid.gov] to ensure proper implementation of our tools,” Alisha Swinteck, a spokesperson for Facebook parent company Meta, said in an emailed statement. “It’s also worth noting that Meta continues to proactively educate advertisers in sensitive verticals on how to properly set-up our business tools.”

Show Your WorkPixel Hunt

How We Built a Meta Pixel Inspector

The first large-scale, crowdsourced study that monitors how Meta tracks people across the internet

The Meta Pixel—the code in question—is present on many websites, marketed to businesses and organizations as a way to track online visitors. When a website uses the code, data on the visitor is sent back to Facebook and can be used by the business or organization to find an audience for its ads. Facebook also retains that data and can use it for its own advertising purposes—although it’s not always clear what those purposes are.

The pixel is extraordinarily pervasive on the web—one prime example of the sort of tracking technology that leads a pair of shoes you looked at to haunt you across the internet, or in this case, on Facebook and Instagram.

Girard Kelly, director of privacy at Common Sense Media, said this sort of code is so widely available that even website operators themselves may not know how they’re tracking their visitors. “They just grab the code from Facebook, copy and paste, and they’re done,” Kelly said. “They don’t necessarily think about the implications.”

Blacklight, a Markup project launched in 2020, found that 30 percent of the 100,000 most popular websites use the Meta Pixel, and Facebook has said millions of pixels are on websites across the internet.

[Website operators] just grab the code from Facebook, copy and paste, and they’re done. They don’t necessarily think about the implications.

Girard Kelly, Common Sense Media

To further understand how the pixel works—and exactly what sorts of data it transmits—The Markup, in partnership with Mozilla, started the Facebook Pixel Hunt project. The project is a crowd-sourced undertaking in which anyone can install Mozilla’s Rally browser add-on in order to send The Markup data on Meta’s pixel as it appears on sites that they visit.

When a user comes across the pixel on the web, the pixel sends information to Facebook about the page they visit. At the very least it tells Facebook who is visiting what pages, but it is capable of sending a lot more. It may tell Facebook which buttons the user clicked and if that person made a purchase or donation, and it sometimes sends personal information such as a person’s name or the email address they entered in a form field. Participants in the Pixel Hunt project share with The Markup what data the pixel is collecting on a given website.

The Rally browser add-on detects the presence of the Meta Pixel as participants browse the web. Mozilla then collects all the data that is shared with Meta through network requests the pixel makes to Meta’s servers. For a more detailed explanation of exactly what the add-on collects and how we analyze the data, please refer to the How We Analyze the Pixel Data section of our methodology.

While the pixel is widely implemented around the web, some privacy advocates say its use on a government form that includes personal information about teenagers is questionable.

Federal student aid forms require a student to enter such information as their, and often their parents’ or guardians’, financial details. While The Markup does not have evidence that everything a student typed in was being collected, the pixel was configured to collect identifying information such as the student’s name, email address, phone number, and zip code, data that could be used for targeting ads on Facebook.

The U.S. government offers more than $100 billion to help students fund their postsecondary education. For many students, the financial assistance is their only means of going beyond high school—and FAFSA is the primary way to apply for federal student aid, which means that, until the Department of Education turned off tracking following The Markup’s questions, only the savviest web users could avoid sending an online application to the government without also providing potentially sensitive information to Facebook.

Leonie Haimson, co-chair of the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, described the data collection as “horrifying,” saying the Department of Education was “asleep at the wheel” on data privacy.

“They are sloppy and they are not focused on doing their job in general on the issue of privacy,” Haimson said.

Tracking Aid Applicants

Facebook’s pixel gathers personal information to fuel its Advanced Matching feature. By capturing information like names and addresses on third-party website visitors, Facebook can check to see whether a visitor has a Facebook account, then place advertisements based on the sites they visited. This feature allows Facebook to track its users even if they block their cookies.

There are understandable reasons a government agency might want to include tracking on its pages, said Jason Kelley, associate director of digital strategy at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. The agency might, for example, want to place a Facebook ad that reminds families about an upcoming deadline to apply for aid. Using data gleaned from the pixel, the government could, theoretically at least, reach out to people who have visited the site and use Facebook. “But the fact that to do that they have to compromise the privacy of their users is a real problem,” Kelley said.

For applicants who went to apply for aid before the recent change, the pixel started tracking them even before they started to fill out the FAFSA form.

From the very beginning, when a visitor entered their email address on the sign-in page, that address was being sent to Facebook, The Markup found.

As families filled out more of the form, the tracking continued—not just on pages requesting parents’ information but also on pages specifically meant to receive students’ personal information.

A page for demographic information on the student applying for aid, for example, was sending names, email addresses, and zip codes to Facebook. Similar data was tracked on pages for student financials and even on pages asking for information on the student’s high school. Facebook generally “hashes” the data, a process that scrambles sensitive data. While it is moderately more secure than sending the data via plaintext, hashing isn’t a guarantee of security.

Hashing does not prevent Facebook from using this data to match people who visit studentaid.gov to their Facebook profiles.

The spokesperson for the Department of Education wrote in the emailed statement that “Federal Student Aid (FSA) does not track the names, emails, phone numbers, or street addresses of visitors to the StudentAid.gov website” but that it does use pixels “to track domains, devices, and URLs, as disclosed in the site’s privacy policy.”

Ad-blocking software can shut down pixel tracking, but for most visitors, tracking like this happens without their knowledge. The tool doesn’t rely on a visitor being signed in to Facebook, or even on having a Facebook account, to work. Only visitors willing to monitor the network traffic would see the data being sent to Facebook.

Facebook has rules around both gathering potentially sensitive financial information and targeting ads to users under 18 years old. The company says it doesn’t want businesses sending data like the amount of a loan or a student’s debt status to Facebook, although the list of banned practices Facebook provides “is not exhaustive,” according to the company. Facebook also limits some types of ad targeting for users under 18 years old.

Swinteck, the Meta spokesperson, declined to specify directly about whether the tool’s use on a government financial aid page violated any rules but said Meta works with organizations proactively to ensure compliance with its rules.

Swinteck said the company also uses AI tools to detect potentially sensitive personal information. “When businesses do this, our filtering mechanism removes any potentially sensitive data it detects before that data can be stored in our ads systems,” Swinteck said. The company didn’t directly respond to a question about whether the data on students entered on studentaid.gov would be considered sensitive.

Where Does the Data Go?

When a company’s website uses the pixel, the company might be trying to understand visitor behavior, like what purchases users make or what pages they visit. That information can be helpful if a business wants to later reach customers who bought a certain product, for example.

While there’s a potential benefit to websites placing the pixel on their pages, it’s not clear exactly how visitors’ data gathered outside of Facebook is later used by Meta.

An internal Facebook document written by engineers at the company and published this week by Vice suggested even Facebook itself often can’t say where the data it collects ultimately goes. “We do not have an adequate level of control and explainability over how our systems use data, and thus we can’t confidently make controlled policy changes or external commitments such as ‘we will not use X data for Y purpose,’ ” the document said.

An unnamed Facebook spokesperson told Vice in an email that the document “does not describe our extensive processes and controls to comply with privacy regulations.… New privacy regulations across the globe introduce different requirements and this document reflects the technical solutions we are building to scale the current measures we have in place to manage data and meet our obligations.”

The ways Facebook tracks users off-Facebook have sparked concern from legislators in the past. When CEO Mark Zuckerberg was brought to testify in front of Congress in 2018, for example, one congressman questioned the founder on how much and what kind of data the company holds on non-Facebook users, including whether the service maintains so-called “shadow profiles”—dossiers of information on nonusers of Facebook.

Zuckerberg responded that the company holds data on nonusers for “security purposes,” like preventing third-party collection of data, and later avoided directly answering a similar question from the European Parliament, saying nonusers could clear their information. Zuckerberg did not specify exactly what information the company collects on them. (Facebook users can view their account settings to see which advertisers target them, but the information doesn’t detail how those advertisers first got hold of users’ information or what information Facebook has on users that made advertisers target them.)

Swinteck declined to answer questions about how data collected through the pixel is used to inform other parts of Facebook’s ad-targeting algorithms. Meta’s terms of service, meanwhile, say the company bundles data collected from tools like the pixel with other data points to improve the effectiveness of ad delivery models and to determine the relevance of ads to people.

But practically any web user browsing the internet runs the risk of getting caught up in Facebook’s advertising machinery, experts say—including while doing something as apparently private as applying for student aid.

“All sorts of companies that you don’t have any affiliation with, whether because you don’t have an account with them or because you’re not signed in, might be collecting information about you,” Kelley said. “Because the ecosystem allows that sort of data-sharing, and rewards it.”

This story was copublished with Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news organization covering public education. Sign up for its newsletters here.

Updates

This article has been updated to reflect a statement sent to The Markup by the U.S. Department of Education after publication.

An earlier version of this article mistakenly referred the the Department of Education as the DOE.