The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

AI seems to be everywhere these days—and more and more, that includes the classroom. Teachers are racing to reckon with the kinds of AI tools, like ChatGPT, that let students breeze through assignments. But beyond discussions of what counts as “cheating,” what happens when teachers use AI?

Frequently overworked and underpaid, teachers are less often talked about as users of time-saving AI tools. This raises many questions: Can such tools be trusted to create curriculum? What happens to the student data that gets fed into any of the myriad new AI startups? Will human teachers one day be replaced?

In this article, seven teachers across the world share their insights on AI tools for educators. You will hear a host of varied opinions and perspectives on everything from whether AI could hasten the decline of learning foreign languages to whether AI-generated lesson plans are an infringement on teachers’ rights. A common theme emerged from those we spoke with: just as the internet changed education, AI tools are here to stay, and it is prudent for teachers to adapt.

Vincent Scotto

K-12 STEAM Coordinator at Pittsburgh Public Schools (Pittsburgh, Pa.)

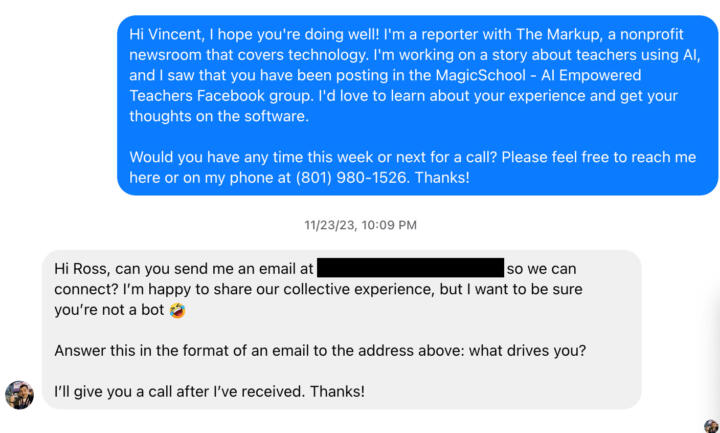

When I first approached Vincent Scotto, a STEAM coordinator at Pittsburgh Public Schools, he tested me. Before honoring my request to interview him about how his district uses AI, he asked me to prove I was a human. Prior to this, I had never considered myself a robot, but here’s what I wrote in my initial message to Scotto:

As I read it over, it was humbling to realize how effortlessly an AI language model could have spit out my message. I braced myself for a conversation with someone I assumed would be a steadfast AI skeptic.

After I passed his challenge, however, I soon learned that he was not such a Luddite at all. Scotto’s views echo the views of many teachers I talked to: with the right safeguards, AI tools can save teachers enormous amounts of time while giving students new, creative ways to explore and practice material.

Scotto has worked in education for over 15 years, starting as an elementary school teacher focused mainly on math and science and working up to his current position as a STEAM coordinator. When he realized that his district did not have a plan for computer science education, he worked to help make one, turning it into a “big focal point” of his district. With the aid of a Pennsylvania state grant, Scotto has worked to make Pittsburgh Public Schools “more 21st century ready,” including readying the district for the coming wave of generative AI.

Hello World

What Happens When Your Art Is Used to Train AI

A conversation with web cartoonist Dorothy Gambrell on the curdled internet, labor, and how we became just numbers

“Most of my role is expanding teachers’ ability to serve students in the way that they always intended when they became a teacher,” he said. But the reality of being a teacher is often very different from how budding teachers imagine it to be. “I’m meeting with a teacher and I’ll ask them how things are going, and usually it’s ‘I’m swamped,’ you know. ‘I don’t have time to talk right now, I still haven’t submitted my lesson plans’ or something to that effect.”

Scotto said he is always looking for new tools to save teachers time, and generative AI is one of his favorite new recommendations—especially tools that are geared toward teachers who are less familiar with technology. MagicSchool AI, a suite of educational AI tools, is one of the most user-friendly tools that Scotto has found, and he frequently demonstrates it to busy teachers.

“I’ll ask them, ‘What’s the topic that you’re going to do for next week?’” he said. Then he plugs the topic into MagicSchool AI, along with his estimation of how much class time that teacher has to teach the particular subject, and lets the AI generate a set of lesson plans. “When a teacher sees how fast [the AI works], they immediately sign up.”

One of Scotto’s greatest fears is privacy, and he recommends that teachers not put any personally identifying information about students—even anonymous demographic information—into AI tools, unless the tool has been specifically approved by the district’s board of education. “For example, ‘My class has 7 Black students, 3 White students’… don’t even put information like that because eventually it becomes a collective of information that you’ve input and… they could make a profile on your students.” He said he worries that the data could be shared or sold to third parties which may use that data for different purposes, putting students at risk now or “50 years from now.”

“We cannot rely on ‘the goodness’ of an organization that intentionally collects data,” Scotto said.

He also stressed the importance of AI policy in protecting students: “People on the ground level, without guidance, may make decisions that [break] policy or law unintentionally. Without AI policy at the federal, state, and local level, these accidents can happen and likely are happening in isolation,” he said.

Hello World

Meet Nightshade—A Tool Empowering Artists to Fight Back Against AI

A newly released research paper outlines a tool artists can use to make their work act like “poison” if it is ingested by an AI image generator

On the issue of copyright, his views were mixed: “Any teacher will tell you that they have borrowed and stolen every idea they’ve had for their classroom. Not a single teacher I know believes they have an original lesson plan.”

He referred me to Teachers Pay Teachers, an Etsy-like online marketplace for teaching materials. “Kids just deserve the best education they can get, and if that means borrowing lesson plans from a bot, I’ll take it. If we’re just teaching lessons, it doesn’t really matter where we got it from. And if the large corporations such as, you know, Pearson, want to sue an individual teacher for copying their stuff with AI, good luck. We’re all in trouble. It is a battle they will lose in the end, because we’ll just stop purchasing their material all together. So it’s a double-edged sword in that way.”

His concerns from AI and copyright come not from the classroom, but on a personal level. “I’m into music and art, and there’s a big worry that artists will lose their jobs, their life blood, because we’re having AI create renditions of Andy Warhol, like, peaches, you know. So I personally don’t use those just because I have personal connections with people that it upsets.”

However, Scotto said that he did not have a “moral qualm” for a couple reasons: “People who really care about art are not buying things that were created by, you know, pixels. They’re looking for a human-created thing with brush strokes and all these things.”

Second, Scotto frequently searches online for Creative Commons images to use in his presentations, and sees no harm in asking an AI to step in. “Could I use a graphics AI to come up with something really quickly, and it would serve my purpose? I sure could. In that instance, it would be innocuous.” Trying to sell AI art or pass it off as your own, however, is “where… it gets into a conundrum.”

Ultimately, just as the calculator revolutionized how students approach math, Scotto thinks AI will change education and teachers should start to adapt. “You’ve got to get in front of [AI] even if you don’t have the kids use it. You’ve got to know what this is, what it’s capable of.”

Sean Fennessy

Teacher at Olney High School, Philadelphia

Sean Fennessy, a geometry teacher, has been in and out of education for around 15 years, dabbling in IT, web design, and activism. His diverse teaching experience has led him to embrace an “unschooling” approach driven by exploration. He uses ChatGPT heavily in the classroom to teach students a lot more than just how to solve math problems.

“So what I do with AI for example, in my classroom, is I have each class have a government, or each class is a country. And I vested them with resources.” Fennessy uses ChatGPT to create a fictional universe, “Fennlandia,” in which students hold elections, stage uprisings, and even purchase snacks in the classroom. He uses the paid version of ChatGPT, allowing him to create a custom chatbot that is confined to this fantasy world.

What does this have to do with geometry?

“The most important part [of geometry] is the application of logic, right? I mean, no one’s going on doing trigonometric functions in the real world… And honestly all of the ones who do, they’re gonna [use] a calculator, right?”

Instead, Fennessy teaches students how to use ChatGPT to code their own small applications to solve problems by using clear, logical language: “AI is going to be really literal about what you’re putting in,” he said, so students must learn to be precise with their instructions. When he demonstrated this approach to his principal in an impromptu classroom observation, his principal was enthusiastic.

His motivations aren’t hidden: “I understand geometry is the end of the line for a lot of my kids. And so, what am I going to give them that’s gonna be useful when they leave here?”

Beyond Fennlandia, he’s used it for other tasks, like generating letters of recommendation for students. He likens ChatGPT to his own children and has watched its skills evolve at roughly the same pace. “It really felt like I was talking to an incredibly bright and amazingly knowledgeable version of my five-year-old for a little while. And then it kind of moved on and I’m like, oh this is like talking to my nine-year-old.” Today, he says, “It’s a college [level] or beyond.”

Machine Learning

Plagiarism Detection Tools Offer a False Sense of Accuracy

The tools that likely brought down Harvard president Claudine Gay are improperly used on students all the time

Of course, not all of Fennessy’s uses for ChatGPT are fantasy. One thing he’s working on for the next semester is creating longer projects that students can complete concurrently with each unit of the geometry course. “One of the problems with projects, especially in math, is always like hey, here’s this project that’s supposed to be a capstone… but you haven’t learned half of [the material] yet.” Fennessy hopes to use ChatGPT to fix this problem by creating projects that unfold over time, to see the bigger picture of how to apply their skills.

Fennessy isn’t frustrated when students cheat with or without AI, but it “doesn’t look like a really good use of [students’] time,” he said. If he catches a student cheating, he asks them to solve new problems on the board to test their understanding.

As far as worrying about whether technology will ever replace him, Fennessy says he firmly believes the “emotional support of a teacher cannot be replaced.” If AI helps his ability to be a cheerleader for his students and spend more one-on-one time with them, then he said he is all for it.

Kim Maybin

Tech Integration Specialist at Ozark City Schools (Ozark, AL)

Kim Maybin taught seventh-grade language arts for the majority of her career. When the opportunity to become a technology integration specialist opened up, she jumped on it. Now she oversees around 200 teachers in her district, training them on using emerging technology to be more effective and efficient with what she calls a “work smarter, not harder mentality… because you’re literally exhausted in that classroom,” she said.

When recommending tools for teachers, cost is one of her main factors: “I’m always looking for something free because we don’t have a lot of money to spend on tools.”

Maybin frequently mentors teachers on how to create custom material for different students using AI tools. As a middle school teacher, she often found herself creating additional structure or “sentence starters” to help struggling students complete their assignments and generating multiple versions of tests that target different depths of knowledge, depending on individual student needs. “Why not let [AI] make the two tests for me? Because now I have more time to focus on the bigger needs in my classroom.”

Maybin thinks it is imperative that teachers get familiar with AI and teach students how to use it appropriately. “If you don’t teach the students how to use it, they are gonna abuse it,” she said. Many of the teachers Maybin works with are initially afraid of the potential for students to cheat with AI, and so they try to stay away from AI in all forms. But if a teacher never mentions AI, she said, students might think they are getting the upper hand on an unaware teacher. “When the students are using it, [teachers are] like ‘They’re using AI!’ and, well, you didn’t mention it!”

The BreakdownMachine Learning

How to Buy Ed Tech That Isn’t Evil

Four critical questions parents and educators should be asking

Instead, she feels teachers need to get more creative by creating “AI-proof” assignments. It’s less difficult than it may sound. Tools like ChatGPT are terrible, she said, at tasks like solving an AP English exam because they don’t have emotions or personal experiences that AP graders are looking for. Requiring students to thoughtfully decide which aspects of their own lives are relevant to the topic of an essay engages them in the subject in a uniquely human way.

Maybin’s district may be a barrier to the adoption of AI by students and teachers alike. Due to privacy concerns, her district initially banned all AI tools. It took convincing from Maybin for her district to begin opening access to AI for teachers, but even then, each application has to be explicitly approved. The tools are still off limits for students, who use locked-down Chromebooks that permit only a small number of education-related programs—both for privacy reasons and concerns about plagiarism.

For teachers who are excited about AI tools, Maybin said they should be aware of being overly trusting of the tools’ accuracy. Maybin recalled that her colleague recommended teachers query ChatGPT about how comfortable it was with a certain topic on a scale from one to 10. “And if ChatGPT gives you nine or 10… it’s really comfortable. [If] it gives you three or four… you need to check it,” although she recommends verifying ChatGPT’s responses no matter the level of its claimed expertise.

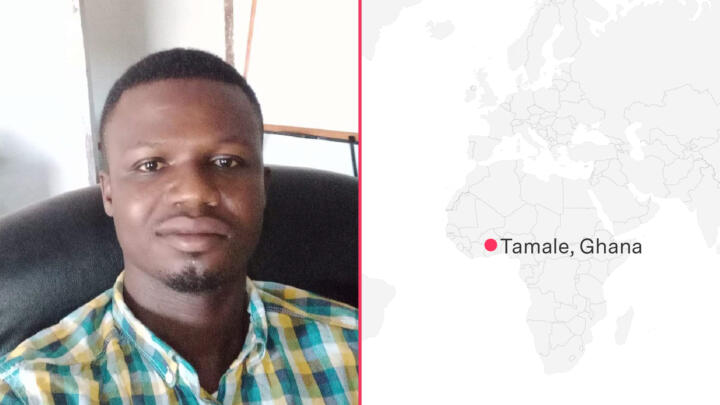

Peter Amoabil

Executive Director, Rural Literacy Solutions (Tamale, Ghana)

Tamale, Ghana is one of the fastest growing cities in West Africa. It is also the capital of Northern Ghana, the region of Ghana with the lowest literacy rates across all ages. Peter Amoabil has been fighting to change that. A teacher for over 14 years, Amoabil balances his duties as a full-time teacher with directing Rural Literacy Solutions, a nonprofit he founded in 2019 to close the literacy gap by offering after-school English literacy programs in partnership with local primary schools.

Recently, Amoabil has been sharing new AI tools to help his teachers. I told him that when I tested an AI tool to generate an explanation of a random topic at a second-grade reading level, the text included words that a second-grade student would not be expected to know. As it turned out, Amoabil found the same thing. “The secret about AI is picking the right tool you need at the moment,” he said.

Hello World

How to Use Sound and AI to Protect the Environment

A conversation with Bourhan Yassin

Another challenge he sees with AI tools is their understanding of local languages. English is the national language of Ghana, so students are expected to read and write English, but the most widely spoken language in northern Ghana is Dagbani. Amoabil has used translation tools several times to translate textbooks into Dagbani, and he often needs to manually edit the translation afterwards to correct inaccuracies.

Despite the challenges, he’s a big fan of many of the tools, including Storybook AI, which generates stories based on a prompt. Amoabil’s teachers have found it to be a great way to create additional reading materials for students to practice reading, while also keeping students engaged by letting them generate stories on any topic they are interested in. He said his students are fascinated by AI and often ask how it works.

Amoabil’s teachers range in age from 26 to 59 years old—60 is the retirement age in Ghana—and most of them are excited about using AI tools. The benefits of Amoabil’s after-school programs are clear: he’s seen English literacy rise substantially for enrolled fourth graders. Amoabil credited AI for some of the improvement, saying that it has helped teachers with a large portion of their workload.

Aaron Shi

Training Coordinator in the Foreign Language Teaching and Resources Center, National Taiwan University

Aaron Shi taught English for over nine years before becoming a teacher training coordinator at the Foreign Language Teaching and Resources Center at National Taiwan University (NTU) in 2022. He mostly works with experienced professors and teachers who’ve been teaching English and other foreign languages, including many who have been teaching college for 10 to 20 years.

Among the teachers that Shi trains, he said he has found older teachers to be generally more interested in learning about AI tools than younger ones. Shi said that many young teachers were too busy fighting for tenure to consider new teaching methods or that they simply felt more comfortable experimenting with AI tools on their own.

One of the most powerful uses of AI, according to Shi, is to create free teaching materials. He envisions a world in which AI can provide personalized learning materials for each student without the prohibitive cost barrier of standardized textbooks.

About 60 to 70 percent of courses at NTU are taught in English, and that number is likely to increase as the Taiwanese government pushes for English to become a required language by 2030. Some of the greatest opposition to this policy has been from teachers: The National Federation of Teachers Unions (NFTU) has argued that teachers are not prepared to teach subjects in English when they are not fluent in English themselves, and students may suffer for the same reason.

Machine Learning

AI Detection Tools Falsely Accuse International Students of Cheating

Stanford study found AI detectors are biased against non-native English speakers

Shi said AI tools can help facilitate cross-cultural communication in ways that support and even go beyond the government’s goals for bilingual education. He said that even if a student does not learn English well, AI tools can help students interact with the English-speaking world. This is especially true for students who choose to stay in Taiwan after graduation and who may not use English frequently in the future compared to those who move abroad.

However, tools that remove language barriers also pose a threat to languages themselves, Shi said. Shi said that the rapid adoption of AI tools may accelerate the decline of Taiwanese languages. According to Shi, Taiwanese people don’t want to speak the same Mandarin language that people in China speak for political reasons, and mainstream AI language models don’t incorporate enough Taiwanese Mandarin sources for results to sound natural.

Along with the rapid adoption of TikTok by young Taiwanese—which he said features predominantly content from China—Shi sees a continuing decline in the standard for Taiwanese Mandarin, as people become less able to differentiate between “authentic” or “good” Taiwanese Mandarin and Standard Chinese.

The same is true for other Taiwanese languages, like Taiwanese Hokkien and the indigenous Formosan languages. “It is hard for AI to be proficient in these languages due to the very limited amount of data,” he wrote in a Facebook message after our interview. “I think the Hokkien dialect (or the Taiwanese language) can also be difficult for AIs to learn, but the number of active users of this dialect/language is, at least, much more than those of the Formosan languages.”

Shi said AI won’t support indigenous languages because it’s not commercially viable to use them. He also said some of these issues are baked into the education system. According to Shi, many parents think it’s O.K. for primary schools to teach indigenous languages in those areas, but in secondary school, students start competing to gain access to better colleges, so they need to learn Chinese and English in order to stay competitive.

Shi said that teachers remain essential to the classroom for the foreseeable future. Even if it is possible to generate teaching materials for an entire course with AI, two teachers might create entirely different versions of the same course simply because of how they prompt the AI. He said this highlighted the importance of educators: knowing how to plan and organize a course requires human insight.

Karle Delo

Curriculum Director and EdTech Influencer, Michigan

Karle Delo, a science teacher and curriculum director in Michigan—and edtech influencer as “CoachKarle” on TikTok—shares reviews of AI tools with teachers worldwide. She has personally tried and reviewed hundreds of AI tools for teachers, and she walked me through how a teacher might apply them in practice.

Delo had me imagine a teacher trying to find an exciting way to teach a lesson on volcanoes and earthquakes. There are five ways she describes AI tools as being handy for this lesson:

- They can be a brainstorming buddy for creative ideas. "Maybe AI could help me think of a 'Would you rather?' question or a real-world scenario."

- AI tools can parse a video about volcanoes that the teacher might play for students, and generate a bullet point summary for students to refer to.

- An AI could differentiate learning and reproduce an article about a real-world earthquake at different reading levels for different students.

- The AI can take real-world earthquake data and write an easily readable analysis. "Normally I'd have to purchase a really, really good curriculum, or I'd have to spend a lot of time putting [the data] in a format that my students can digest because if I just look up earthquake and volcano data, it's probably going to be not in a very student-friendly format.”

- AI is great at generating review questions for students to practice the material.

While AI tools can be powerful for teachers, Delo reminds teachers that they need to be aware of their strengths and weaknesses. “AI could be used to create busy work for kids and that’s not very meaningful,” she said, and teachers might end up with boring slide decks and low-quality multiple-choice quizzes.

Hello World

How AI Is Helping Us Learn About Birds

Machine learning is powering new insights into how birds migrate—and forecasts about where they’ll go next

Delo said that since the internet made just about anything a Google search away, science education has evolved from lecturing on rote facts to engaging students in a process of analysis. In the same way, she believes teachers should approach AI with honest conversations about its potential.

Some teachers see AI tools as closing gaps in access to quality education materials. According to Delo, there is a common misconception that all teachers at all schools are expected to create their lessons from scratch. In reality, it’s common for teachers and districts to purchase curricula from various companies. In the past, this has led to wealthier schools having access to better curricula, while less wealthy schools need to create more content on their own. But AI can help bridge that gap. “If I were a parent, I would want my kid to have a teacher that uses AI,” she said.

She cautions teachers, however, to adhere to privacy laws regarding the use of AI tools. “I know ChatGPT is not approved for use by anyone under the age of 13. When an AI tool has an age restriction, schools better follow it.”

Ultimately, Delo does not see AI replacing teachers anytime soon. “When you think about your favorite teacher, it’s usually a teacher who inspired you. I’ve never really been inspired by AI. I’ve gotten excited about it, but I’ve never been like ‘Wow, this ChatGPT really believes in me today, and that feels good,’” she said. “If technology could have been a replacement or a silver bullet for education, then students would [have] come out of the pandemic with flying colors. And we didn’t see that. We saw that a lot of students struggled with online learning. So I do think the human element of teaching is so important.”

Nathaniel Decker

Teacher at Olney High School, Philadelphia

Nathaniel Decker, an English, poetry, and public speaking teacher in Philadelphia, said he was worried that AI tools would change expectations of teacher productivity. “Teachers using these AI programs to be efficient and save themselves time is great,” he said.

“I’m not anti-technology, anti-automation. I’m anti those things replacing the opportunity for people to make a living off of their work,” he said. Decker, who is involved in the school union, said that teachers should have control over their own use of AI. “I’m fine with teachers using AI, as long as we’re not forced to use AI.”

Decker also said teachers should be contractually in control of their IP, and that they should not be forced to give up their lesson plans to be used in an AI model. “I don’t trust that the people in charge are gonna have everyone’s best intentions at heart,” he said.

One useful area of AI tools for Decker is making sure that teaching materials hit certain mandatory standards from the district and discovering how existing materials might cover more standards than anyone realized. “I intend for this [lesson] to teach this skill, but [it] is also touching on these 12 other skills… That’s a cool way to use [AI] that I never would have thought to use.”

Zine: How We Illustrate Tech (and AI) at The Markup

A lot of what we cover is tough to visualize. We've developed a number of tricks to help—and a comic to tell you all about them

When it comes to students using AI, Decker said, “Anything involving text, writing, or speaking is gonna be the trickiest” to handle as a teacher. When a student submits work to Decker that doesn’t make sense, he has a hard time telling whether the student is making a purposeful creative choice, struggling with the material, or using an AI to generate their work. He cares less about the end product than the creative process, so he does not want students using AI to skip this process. ChatGPT is still banned on Olney High School’s network.

Some teachers have begun to use AI to evaluate student work, but he said that teachers disagree on when it’s appropriate to do so. Decker said, “From an English teacher’s perspective, reading essays and poetry and giving feedback [with AI], I don’t think [teachers] should do that. I don’t know how they could do that in a way that’s differentiated to each students’ needs.”

Decker said that he’d like an AI tool that could help find common problems across all student work for a topic. “If… AI could tell me, ‘This many students understood it, this many didn’t, here’s the issues that they had,’ that could be incredible,” he said.

Eyeing the stack of papers that need to be graded over winter break, he said that he wished he could give feedback to students sooner, but he just didn’t have the time.