Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Hello again,

Two weeks ago I shared how I was trying to find an ethical way to use generative AI in the newsroom. As I was writing that article, I came across someone who was thinking about the same issues in a different discipline.

Maywa Montenegro is an assistant professor of agroecology, the study and practice of food systems transformation, and critical technology studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She wrote and edited for Seed, the now-defunct science and culture magazine, where her reporting on the intersection of sustainability and food systems inspired her to get an environmental science PhD.

In August, Montenegro shared the AI policy she created for her classes: AI policy: a critically engaged approach. As soon as I read it, I knew I’d found someone who was struggling with the same questions I was. I reached out to Montenegro to talk about why she’d written the policy and how it had been received. We discussed technology hype cycles, how AI detection software turns professors into cops, what AI is really good for, and, briefly, lettuce-harvesting robots.

Our conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Tomas Apodaca: Let’s start by talking about AI. Is AI a part of your regular coursework?

Maywa Montenegro: AI is not a central area that I research or write about. Probably the closest that I come in my own scholarship is in the realm of digital agriculture, where we have some projects that are at the cutting edge of where agricultural systems are butting up against all forms of digitalization: internet of things, remote sensing, many kinds of tools that are digital, and some of those are also machine-learning–enabled now. One of my grad students works on automation in Salinas Valley lettuce, these robots that are being trained to harvest.

Apodaca: How did you realize that the use of AI in your courses was something you needed to address in a written policy?

Montenegro: Because I am a scholar of science and technology studies (STS), I’ve been following AI’s development for some time. I won’t credit myself with being one of the early whistleblowers on this, but it has a specific contour that we talk about as “hype cycles.”

There are these technologies that receive extraordinary inflations in interest, in our economy of interest, in investments—especially in Silicon Valley. And then they tend to fizzle. They don’t usually die away completely, like we saw with crypto, but the attention certainly dies down.

Fast forward to the release of ChatGPT. The narrative surrounding AI is that people will be “left behind” unless they adopt it ASAP. How is AI going to revolutionize education? How is it going to transform agriculture? How is it going to make logistics a million times smarter? Almost every sector is being faced with the proposition that they should jump on the AI train or risk getting left behind.

To my frustration, rather than having concerted, critical, and honest conversations around who benefits from this technology—and why and how—we’ve been sold the idea that it’s inevitable, and we better figure out how to make use of it, to deal with it as best we can. People respond to that in different ways, but the policies that have been encouraged at UCSC have not been top-down, like “You must use it in your class,” but, “You must at least provide language in your syllabus that explains to students what your expectations are.”

That was my moment where I realized, OK, I’m going to have to figure out what are the rules, in terms of using AI for homework and assignments and exams. Then, in my philosophy of teaching, I’m really committed to not using a “stick” approach with students, in the metaphor of the carrot and the stick.

I could see some approaches to AI being more punitive, like “I will do this and this if you use AI,” or I’m going to do Simone Biles types of gymnastics in order to create assignments that will try to impede you from using AI. That seemed like adding extraordinary labor to teaching when it’s already challenging enough, and somewhat of a cat-and-mouse game. These students are super smart. Students were even writing articles in the Chronicle of Higher Education about how they were getting around teachers’ new assignments.

I really wanted to approach my students as empowered agents of their own learning and to express to them, in the best way that I could at the time, what my reservations are. Not just with the tool in a technical sense and how it, as many people have confirmed, is much more like a stochastic parrot than it is something that learns or that is cognitive.

Beyond that, there is the larger “assemblage” of AI that enables these systems to run in the first place. Since I’m an environmental studies professor, it became clear that a lot of those pieces were an entire material world of energy, water, and other resources; of labor undervalued and exploited. And there’s the racialized and encoded assumptions that emanate through the texts upon which these chatbots are trained.

That became exciting to me. I hope that in combination with the content of my class, students would become either revolted or simply disinterested in using AI in class assignments. That was the goal.

Apodaca: How did it play out with your students?

Montenegro: I heard a few prominent reactions. One is that the students felt really grateful that a professor had taken time to provide them with a context for understanding ChatGPT.

And the second response was, “Wow, we had no idea about the labor part!”

Hello World

This Journalism Professor Made a NYC Chatbot in Minutes. It Actually Worked

Jonathan Soma on the power and pitfalls of AI and chatbots

Towards the end of the course, I sent out a survey to the students and asked whether they had ever run across a policy like this before. Were there things that they would like to see added? Were there things that they had not known before and learned? Most of them said that they had never seen a policy like this before. So that was interesting for me to learn. And many of them responded by mentioning the environmental impact. I think that really strikes a nerve with students who are environmental studies majors.

The responses were, “I’m even less likely to use this than I was before,” which made me feel more than happy.

Apodaca: In the policy, you tell students that they can reach out to the teaching team if they feel pressured to use these tools for your course. Did that ever happen?

Montenegro: That did not happen.

Apodaca: Do you think that’s a good thing, that nobody reached out?

Montenegro: I might have a biased sample, given that the students are in a course on principles of just and sustainable agriculture.

I was listening the other day to folks talking about, “Is the bubble going to burst?” This hype spike has been so high that I don’t think it’s going to just collapse and vanish. It’s going to be here, including in journalism, which has been something that concerns me a lot as a former journalist. I am here for that long conversation.

I’m a researcher who works in the publishing world and peer review journals. A few weeks ago, it was made public that Informa, the parent company of Taylor and Francis, and another large publishing firm had signed a contract to train OpenAI models on language from the peer review journals. But authors who put their research into these journals were not made aware. I’m an editor of an Informa-edited journal and I was not aware.

That’s just wild to me, that these contracts are being signed and then they say, “Don’t worry, copyrights are still intact. We’re not going to have big passages reused, that’s going to be OK.”

There is such an entitlement that, like, everything is fine. We are already publishing not-for-pay in these journals. And the fact that that text would then be repurposed and sold as training data… that contract was several million dollars.

It’s things like that that frustrate me because it’s going back to the pedagogical value: Why are we doing this?

Hello World

A New, Dirty Vision for Higher Education

An interview with Julia Schleck, who argues that rather than serving the public good, universities should be a forum to define and debate the public good

Even if you believe that the machine is learning, your brain is not learning. And you might be in debt—tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars—from your education. Do you really want to walk away without having given your brain, your mind and intellect, the gift of that learning, even if it’s a struggle? That blows my mind. Why would we do this? Please don’t.

That’s where I’m at with it. And I think students respect it when you aren’t approaching them with this as a punitive measure because then they’re going to react and want to use it just to piss you off, honestly. Or because they’re curious. And they ought to be curious!

But I’m curious whether it will show up on the other side, where for a long time we’ve had challenges in finding peer reviewers because there’s just a surplus of papers coming in relative to the available labor to peer review. How long is it before they tell us, “Just as a first pass, consider using our new Informa-trained ChatGPT to whittle down the stack of papers?”

Apodaca: Education technology is a big industry, and generative AI is only its most recent innovation. Have you used ed-tech in the past and has it helped you as an educator?

Montenegro: Technology for me… we could definitely go down a rabbit hole here. In agriculture and in food systems, it’s hard to define. Is a “technology” a fence? If it has some relation to the system of production in an applied fashion, where do we bound technology?

For me, it’s most useful to think of it as a system of world-making. It’s not just that tool that we can see. It’s all of the infrastructure, the political economy, the knowledge that enables it and that it in turn enables. So I can’t not use technology in education. It wouldn’t make sense for me.

I have had the gift of a mentor who’s non-hearing, and text-to-speech recognition has been game-changing for us in terms of our capacity to converse. It is machine learning that does this speech recognition.

And Google Suite—although it does not make me happy to enrich Eric Schmidt—those kinds of things have helped a lot. I have experimented with live polls, collaborative annotation tools. As we’ve been able to return to the classroom in real and embodied space, just having conversations—I think students really crave face-to-face time, contact, dialogue and allowing that to breathe. In the past year, especially, that has been much more of a pedagogical game-saver than any new tool that I’ve introduced.

Machine Learning

AI Detection Tools Falsely Accuse International Students of Cheating

Stanford study found AI detectors are biased against non-native English speakers

Apodaca: There are AI detectors out there, and TurnItIn is probably the most well-known in the educational context. Do you use TurnItIn?

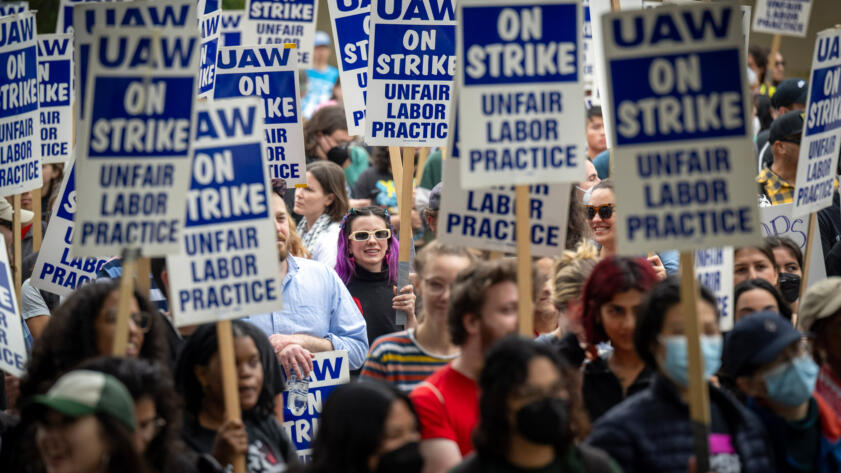

Montenegro: No. I am an abolitionist. So I believe in anti-carceral frameworks, not in policing and patrolling people, including my students. A tool that uses AI to detect AI, because it is embedding racially encoded language, is almost certainly going to have problems with false detection. Even if it’s correct, you will wind up monitoring and potentially penalizing students who struggle with language. This leads to all sorts of problems in terms of bias in the classroom. I don’t want to be a cop in my classroom.

The university does not allow us to use detection technologies in our classroom unless certain standards are met. That is a constraint at UC Santa Cruz.

Ruha Benjamin’s fabulous book “Race After Technology” goes in-depth into this, not even in the realm of AI, per se, but this is an older thing of technology. Ruha’s point about redlining and predictive policing—which had been built on racially-encoded maps of where people live and aren’t allowed to live and get mortgages for houses—AI produces these models in which we are reinforcing and perpetuating systems of violence through the perceivably neutral and unbiased language of the algorithm. “How can it be racist? It’s just an algorithm!”

Apodaca: In the policy, you write, “many of us are trying to figure out what AI is, what it is good for.” Have you figured it out? Have you thought of anything that it’s good for?

Montenegro: For me, as a scholar of technology, I think it has opened up a lot of discussions in terms of what we value and why. When we’re talking to our students about all of the things that ChatGPT is and isn’t, what it does and can’t do, I think at the core of it we get down to: “Why are we doing this? Why are we here?”

Sure, you could use this even though it uses so many million gallons of water when we are in the midst of a drought in California; when we know that it’s using gargantuan amounts of energy and we’re fighting desperately to control the climate crisis; and that it extracts labor from underpaid workers in Kenya and we are talking about racial capitalism.

The gifts of AI come in weird ways.

Maywa Montenegro

Even if you decide, “This is a hard time for me. I have to get my passing grade or I’m going to flunk out,” I want to honor that. I want to honor that students are in this struggle, but also, what is the role of education and why are we doing this at all? Because you can get your grade and you can get out of here. But at the end of the day, why do we care about any of this? What’s it worth?

AI has—inadvertently, for sure—brought up those root-cause problems of systemic crises and enabled us to have conversations about them.

One of the reasons that I put the policy out on Twitter (now known as X), in the spirit of putting it out into the world: I’m inspired by the Indigenous Métis scholar Max Liboiron in Canada. They are also indigenous STS and they put a lot of their resistance pieces on Twitter before they left the platform. I wanted to just put it out there, let people adapt, reuse, and hope that people would tell me stories about how it would be useful for them, if it was. And in the past few days, I’ve actually gotten emails from colleagues saying, “Is this true? Can we actually use this?” And it has sparked some conversations.

So that’s really fulfilling for me, just having that kind of community interested in charting a different path and engaging students critically in questions of technology. The gifts of AI come in weird ways.

When I shared my thoughts about ethical AI use in the newsroom two weeks ago, I asked you to let me know how you’re grappling with AI in your own homes and offices. A handful of you took the time to write very thoughtful responses. If you find these articles thought-provoking, I’d still love to hear from you, write to me at tomas@themarkup.org.

Thanks for reading,

Tomas Apodaca

Journalism Engineer

The Markup / CalMatters