In a 3–2 vote on Nov. 15, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) passed rules that represent a historic step toward closing the digital divide.

As part of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Congress mandated the FCC adopt rules to prohibit “digital discrimination of access based on income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion, or national origin.” Since the infrastructure bill was relatively scant on details, many of the specifics on how it would be implemented will be decided by the FCC.

Still Loading

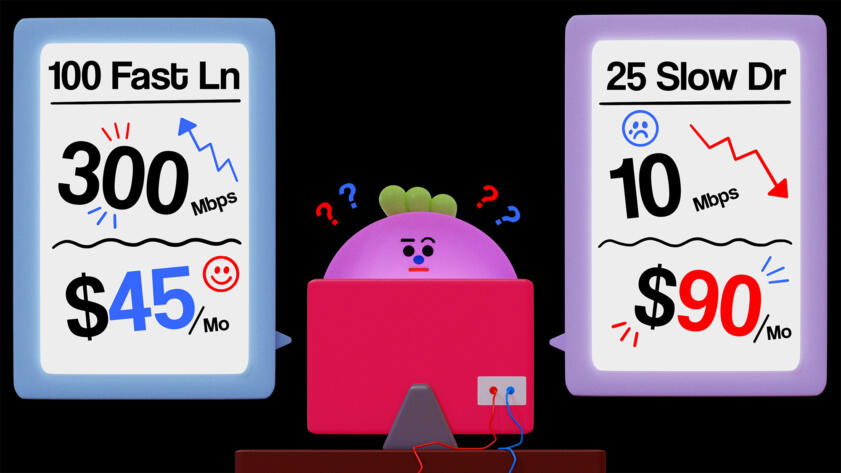

Dollars to Megabits, You May Be Paying 400 Times As Much As Your Neighbor for Internet Service

An investigation by The Markup found that AT&T, Verizon, EarthLink, and CenturyLink disproportionately offered lower-income and least-White neighborhoods slow internet service for the same price as speedy connections they offered in other parts of town

Last month, the agency published a report on its new initiatives and rules aimed to address digital discrimination. What’s laid out in the report was approved in the FCC’s vote.

“The trajectory of digital progress has not always been even, has not always been fair, a result that has held back our collective achievements as a nation,” said Commissioner Geoffrey Starks, who voted in favor of imposing the rules. “Eradicating digital discrimination anywhere will empower individuals everywhere. This is a proceeding that will impact generations of Americans to come, and will work to ensure a more just and equitable future for tomorrow.”

Commissioner Brandon Carr, the senior Republican on the Commission, voted against the order, calling it an unprecedented power grab by the FCC.

“The Biden administration’s entire approach to the internet, its entire agenda, can be boiled down to one single word: control,” Carr said, tying the digital discrimination rules to the administration’s efforts to reinstate net neutrality and push social media platforms to combat online misinformation. “You can see it today as the Biden administration has called on the FCC to adopt these digital equity rules—a framework that gives the FCC a nearly limitless power to veto private sector decisions.”

For the first time, internet service providers (ISPs) can now be penalized by the FCC for implementing policies that result in certain communities getting relatively worse service or fewer opportunities to purchase service. ISPs could be fined if they are caught engaging in conduct that’s discriminatory and “not justified by genuine issues of technical or economic feasibility,” which will be determined by the FCC on a case-by-case basis, and based on what other ISPs have been able to do in the past.

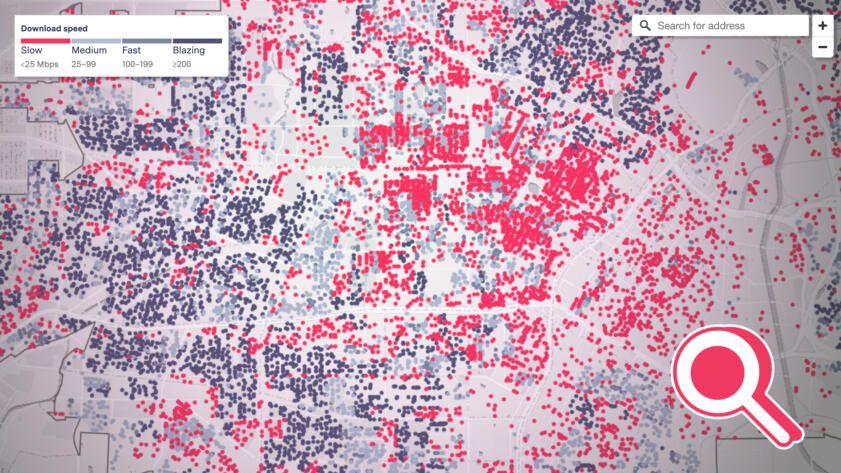

Still Loading

See the Neighborhoods Internet Providers Excluded from Fast Internet

Explore The Markup’s interactive map to see where AT&T, CenturyLink, and Verizon offered only slow internet speeds in major U.S. cities

Crucially, the report notes that an ISP’s conduct will not be found discriminatory solely because inequities exist on the ground. “We will require that any determination of differential impact that relies on observed disparity must point to a specific policy or practice that is causing the disparity,” the report reads.

These policies also apply to nontechnical elements of internet service, like how a marketing company hired by an ISP targets its advertising or the language options offered for customer service for a local government’s municipal broadband. Policies deemed discriminatory are ones that cause inequitable access going forward, after the new rules go into effect. Older policies—the ones that may have caused the digital divide that’s opened over the past few decades—will be outside of the rules’ purview.

USTelecom, a broadband industry group, made its position on the rules clear in a post on its website: “However well-intentioned, the FCC’s draft rules create a regulatory structure that could stifle investment and force providers to divert limited capital away from deployment,” USTelecom President and CEO Jonathan Spalter said in the post.

In addition to punishing instances of explicit discrimination, the FCC can identify when a company has engaged in digital discrimination by using a standard called “disparate impact,” which is the idea that different groups can experience markedly different outcomes, even when the policy causing that disparity isn’t explicitly about any characteristics defining a group. For example, a Department of Housing and Urban Development program aimed at helping rebuild New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina based the amount of money given to each household on the value of the home instead of the cost to rebuild. Since homes in Black neighborhoods tended to be worth less, program participants in those areas tended to get less money.

Hello World

Who's Afraid of Disparate Impact?

The answer could be crucial in the FCC’s attempt to combat “digital discrimination”

Whether to use the disparate impact standard was a major battleground during the FCC’s rulemaking process, with activists arguing in its favor, and ISPs (along with ideologically aligned think tanks) arguing that something should only be considered discrimination when a company’s policy is explicitly based around a protected category, like race or income.

“For decades the disability community has noted that discrimination occurs unintentionally and often results from seemingly neutral policies that result in discrimination,” the American Association of People With Disabilities wrote in a comment to the agency, pushing for the use of disparate impact. “Too often disabled people experience discrimination not because of malicious intent or explicit exclusion within programs or policies but because the disabled people were simply not considered in the first place.”

“Adopting a disparate impact test would cause carriers to choose between prioritizing deployment based on closing the digital divide, as required by Congress, and paralyzing deployment for fear that a regular, common business decision may disproportionately affect a minority community,” the Lincoln Network, a free-market think tank, countered in its own comment to the agency earlier this year.

Speaking at the First Congregational United Church of Christ in Washington, D.C., the day before the rules were posted publicly, FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel explained why the agency needed to be able to act on facially neutral policies that are discriminatory in execution.

“What the record shows is that there are gaps in access for low-income, rural, Tribal, and minority communities. It shows that the digital divide significantly tracks the housing redlining that came into existence under the National Housing Act of 1934. It shows that many of the communities that lack adequate access to broadband today are the same areas that suffer from long-standing patterns of residential segregation and economic disadvantage,” Rosenworcel said. “And it shows that these gaps in broadband access stem from policies and practices that may be neutral on their face, rather than the result of intentionally discriminatory conduct.”

To help identify discriminatory policies, the FCC created a way for the public to submit complaints about ISPs. These complaints won’t necessarily begin a formal adjudication process against the ISP, but they can be used as a basis for the FCC to begin its own investigation into the provider’s conduct.

The BreakdownStill Loading

How to Search for a Better Deal on Broadband

You might even be able to help improve crucial government broadband data in the process

In a letter to the FCC sent last week, Angela Siefer, executive director of the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, which provides support to connectivity advocates across the country, expressed approval for many elements of the FCC’s rules. Siefer hailed the agency’s “approach to evaluating technical and economic feasibility on a case-by-case basis, rather than adopting safe harbors” and “application of the rules to technical and non-technical aspects of service, including pricing.”

At the same time, the letter highlighted a number of potential problems with the proposal, like what to do about long-standing patterns of ISP behavior that started before the rules were enacted but will continue into the future. “NDIA asked the Commission to provide guidance articulating what evidence it will consider to evaluate ongoing behavior, such as the persistent gaps in AT&T’s broadband technology and speeds offered to locations in higher and lower income Census tracts in Cleveland,” Siefer wrote.

In a related proposal announced in October, but not approved as part of the Nov. 15 vote, the agency will also require ISPs to submit annual reports showing all major upgrades made to their networks over the past year, information useful to determine if an ISP is neglecting system upgrades in marginalized communities. ISPs would also be required to launch an internal compliance program to evaluate if they are engaging in “digital discrimination.”

The Markup’s reporting on the digital divide played a small part in the FCC’s rulemaking process.

An investigation we published last year showed that a quartet of major ISPs disproportionately charged households in lower-income, less White, and historically redlined neighborhoods in dozens of cities across the country the same price for slower internet plans than they were offering for faster speeds in other parts of town. In its notice of proposed rulemaking, released shortly after our story, the FCC specifically asked the public for comment about our investigations and “what accounts for the disparities identified.”

As referenced in the FCC’s October report, the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, Common Sense Media, and a coalition of 39 nonprofit groups that included the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Open Technology Institute, submitted comments pointing to our story as evidence why the FCC needed to act to rectify long-standing inequities in broadband deployment.

Build Your Own Dataset

Slow Internet? Find Out What Side of the Digital Divide You’re On

All you need to test for disparities in internet speeds and pricing is a computer, internet access, a Google account, and some free time

Conversely, AT&T, telecommunications industry group ACA Connects, and the pro-business think tank Free State Foundation all submitted comments criticizing our investigation. These organizations submitted similar criticisms of other studies showing ISPs’ contributions to the digital divide by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, Free Press, the Communication Workers of America, and the Greenlining Institute.

(You can read AT&T’s criticism, which was the most robust, and our own rebuttal, which was also submitted in a comment to the agency.)

Mandating that the FCC take action to combat digital discrimination wasn’t the only part of the infrastructure bill aimed at closing the digital divide. The bill apportioned over $42 billion for the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program to build high-speed internet infrastructure, primarily in areas of the country where residents don’t already have the ability to subscribe to any type of broadband internet service. As FCC commissioners noted during the Nov. 15 hearing, ISPs that participate in BEAD and comply with its equity rules are exempted from being hit with digital discrimination enforcement.

In addition, the legislation allocated $14.2 billion for the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), which provides a $30 monthly subsidy ($75 for households on tribal lands) to cover internet or wireless service.

According to data compiled by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, more than 21 million households are currently using the ACP, which is projected to run out of money next summer unless Congress secures more funding.