This article is part of “On Borrowed Time” a series by Anissa Durham that examines the people, policies, and systems that hurt or help Black patients in need of an organ transplant.

Teenagers aren’t supposed to struggle to breathe.

But two years ago, Micah Clayborne, a then-active 13-year-old middle school tennis player, knew something was wrong. Still, he pushed through the symptoms — persistent sweating and shortness of breath — for six months before finally telling his parents. They rushed their son to the hospital. Within days, doctors diagnosed Micah with Danon disease — a genetic condition that thickens the heart muscle.

On Borrowed Time

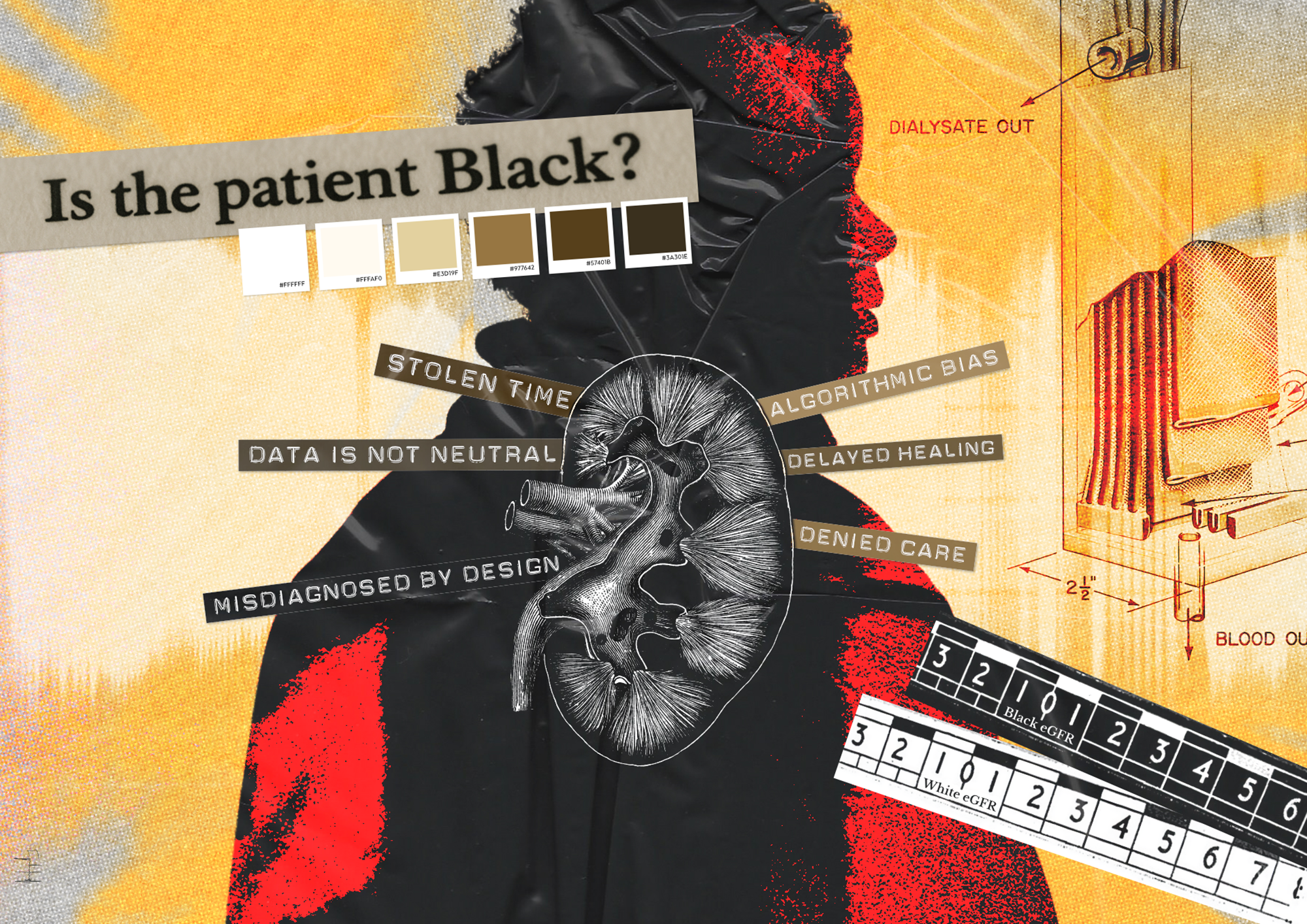

Is the patient Black? Check this box for yes

For years a race-based medical calculation delayed Black patients access to life-saving kidney transplants

His heart was failing — and he was dying.

Within weeks, doctors added his name to the national heart transplant waiting list. He ranked second in line. His birthday passed. And then, 10 months later, he finally received his new heart. Now 15, Micah says the experience changed how he sees life — and opened his eyes to the toll it takes to be on a transplant wait list.

“Not everyone gets transplants often,” Micah says. “Getting a transplant has shown me how it’s affected other people.”

Micah was one of thousands of Americans each year who unexpectedly find themselves needing an organ transplant. Last year marked a new record in transplantation, with 48,000 Americans receiving a new organ. But there’s still a shortage of organs. And about 17 people die every day waiting for a transplant.

In Word In Black’s “On Borrowed Time,” series, we’ve explored why there is so much mistrust among Black folks toward the organ donation process, what barriers block their access to care and the equity and ethical issues surrounding organ donation. We also put a spotlight on the Black lives changed through the transplant system.

We’ve compiled a list of 10 common questions, and well-informed answers, to help explain the process of organ donation, procurement, and transplantation. Here’s what experts shared with us.

1. What does it mean to be a registered organ donor?

A registered organ donor is someone who has decided that, when they die, their organs or tissue may be donated to someone in need. Donors can decide which organs they want to donate, and any adult can register. People under 18 can register with a parent or legal guardian’s consent.

On Borrowed Time

It’s hard to find resources while on the transplant list. These sites want to change that

Here are seven resources to help if you need an organ transplant

There are several places where adults can register. Any local Department of Motor Vehicles service location, through a local organ procurement organization, or the Donate Life America national registry. Some states even let you sign up while you register to vote. If you register as an organ donor after you’ve been issued a driver’s license or state identification card, you won’t automatically be issued a new one. So not everyone who is registered will immediately have the donor icon on their state-issued ID.

Today, about 170 million Americans have registered as donors. Unless you remove your name from a donor registry, organ donation is legally binding — even if your family objects. State laws follow the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, which protects a person’s right to donate after death.

2. Who needs an organ transplant?

More than 105,000 people are on the national transplant waiting list as of 2025 and about 92,000 of them need a kidney. Black Americans make up the second largest group of people on the wait list, with roughly 32,000 people waiting for a kidney transplant.

3. What are OPOs?

Organ procurement organizations, or OPOs, are nonprofit entities in each state responsible for recovering organs from deceased donors. The federal government oversees 54 OPOs nationwide through two federal agencies in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).

In 2020, CMS updated the requirements OPOs must meet to receive Medicare and Medicaid payments. Every four years, CMS evaluates and ranks OPOs and places them in one of three tiers based on their performance. Those in the lowest tier lose certification. The current recertification cycle ends on July 31, 2026.

4. How are organs allocated for transplantation?

The U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, or OPTN, is managed by UNOS — the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit organization which plays a key role in allocating organs. A computer system matches donors and recipients, filtering out anyone who doesn’t meet the criteria — mismatched blood type, height or weight, or immune system incompatibility matching for a kidney or pancreas.

Organs can only survive for a short time after removal from the donor. They can’t be frozen or stored for days or weeks. Because they expire quickly, a transplant can only occur when the recipient is within a certain distance of the donor. Priority goes to recipients closer to the donor’s hospital.

Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act in 1984, which prohibits the sale of human organs and established OPTN to manage organ allocation and national registries. The law aimed to address the shortage of organs available and improve the matching process.

Alexandra Glazier, professor of health policy at Brown University and president and CEO of New England Donor Services, which runs an OPO, says part of her work focused on reforming the use of designated service areas, or DSAs. These geographic zones, defined by OPTN, were initially used to determine the allocation of organs — meaning, organs were first offered to candidates within the donor’s DSA. But, opponents of the system argued, this often overlooked candidates who were sicker and increased inequities. Now, the system uses a 250 nautical mile circle around the donor hospital as the primary means for allocation, a system that has its own critics.

Organ Failure

Poorer States Suffer Under New Organ Donation Rules, As Livers Go to Waste

Life-saving liver transplants have plummeted in some Southern and Midwestern states with higher death rates from liver disease, while New York and California have made big gains

“We’re in a moment of flux in these reforms. We have the opportunity to do better,” Glazier says. “We’re better than we were with some of the disparities I was focused on, but we need the feedback and data to be continually evaluated … towards that goal of improvement.”

UNOS generates a ranked list of potential recipients for each organ. OPOs then share detailed medical information about the donor with transplant teams. Ultimately, it’s up to the surgeon who is offered an organ to accept it for their patient.

5. Is it true physicians won’t work as hard to save my life if I’m a registered donor?

A common belief in Black and Brown communities is that if you are a registered donor and you end up in the hospital in critical condition, physicians might cut corners or allow you to die to “harvest” your organs. But several key facts show why this is a myth.

If you die before getting to the hospital, your organs can’t be used for transplant. Viable organs require oxygen and blood flow up to the point of removal. On average, only 1% of people die in a way that allows them to be an organ donor.

Because most donated organs come from deceased donors, very specific circumstances must occur for someone to qualify. The two main types of death that allow organ donation are brain death — when a patient’s heart is beating but a physician has declared them brain dead — and donation after circulatory death, when a patient is taken off life support, the heart stops, and the patient is declared dead.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act is a federal law that requires doctors to treat and stabilize patients, regardless of insurance status. When someone arrives in critical condition, physicians are expected to do everything possible to save them. In most cases, emergency room doctors don’t even know whether a patient is a registered donor.

If a patient is near death, a separate team, like one provided by an organ procurement organization, manages organ recovery. There are nearly 5,000 hospital emergency departments in the U.S., but only about 250 transplant centers to which donated organs need to be moved.

6. How many Black Americans are registered organ donors?

Donate Life America, which has access to the national organ donor registry, does not track data on race and ethnicity. A few states collect this demographic information, but it is still optional for an individual to provide this information.

In a recent survey conducted by Word In Black, we asked 1,588 Black Americans about their attitudes, behaviors, and motivations around organ donation. When asked “Which of the following best describes your current organ donor registration status?” nearly 50% said they’re registered organ donors. About one in four said they aren’t registered, and either don’t plan to register or would like to learn more about it. Another 8.5% said they were previously registered but are no longer.

7. Have racial bias and disparities played a role in organ transplantation?

Dr. Joseph Keith Melancon, director of transplantation at the George Washington University Hospital, is a kidney and pancreas transplant surgeon. He says that more than 20 years ago, when he began his career, the system wasn’t as equitable as it is today, for a few reasons.

Since the late 1970s, computer algorithms have matched organ donors with recipients. But these systems are susceptible to biases that contribute to or exacerbate the existing racial disparities in organ allocation. In 2003, the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, led a process to rewrite the kidney transplant algorithm to address equity issues.

“I thought it was truly happenstance that the system was discriminatory because I thought it was biological,” Melancon says. “Over time, rules were changed to make access better for Black people.”

Black people are nearly four times more likely to develop kidney failure than white people, and more than one-third of dialysis patients are Black. On average, dialysis centers make anywhere from $35,000 to $150,000 per patient per year from Medicare or private insurance reimbursements. And for decades, some doctors failed to refer their mostly Black patients for transplants — even though kidney transplantation is cheaper than dialysis.

In 2019, President Donald Trump launched the Advancing American Kidney Health initiative and signed an executive order that created a new payment system for kidney treatment. Five new payment models, introduced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, incentivize clinicians to focus on preventive care and kidney transplants and shift away from facility-based dialysis. Medicare Part B is now required to pay for immunosuppressive medications for the lifetime of a kidney transplant recipient.

“Some people are surprised when I tell them that equitable access to transplant increased during the first Trump administration more than it did during the Obama administration or the Biden administration,” Melancon says. “So this was a ‘win-win-win’ sort of legislation.”

8. Why are organs discarded?

Each year, about 28,000 donated organs are discarded nationwide, according to the U.S. Organ Donation and Transplantation System. Kidneys are discarded the most — even though they’re also the most in-demand organ.

Although organ procurement organizations recover organs, hospitals make the final call on whether to accept a donated organ. Some of the most common reasons organs get discarded include quality concerns, logistical challenges, and transplant center standards. Many transplant surgeons don’t want to accept an organ that doesn’t meet their hospital’s standards, or that they feel isn’t the best match for their patients. If one surgeon declines, the organ is offered to the next candidate’s transplant team.

Melancon said some donors are categorized as higher-risk, for example older patients with more comorbidities like diabetes or hypertension. If no surgeons accept their donated kidneys, they will end up discarded.

“Our primary responsibility is to our patients, transplant surgeons are reluctant to use kidneys that may not work well,” Melancon says.

9. How does insurance coverage play a role in who gets an organ transplant?

In the U.S., people without health insurance rarely make it to the transplant wait list or receive an organ transplant. Out-of-pocket costs range from $1.6 million for a new heart to $409,000 for a pancreas transplant. Health insurance determines access to care, placement on the wait list, surgery, and post-transplant anti-rejection medication.

On the other hand, a deceased donor doesn’t need health insurance — highlighting a deep injustice in the organ transplantation system. Poor, uninsured people can donate an organ, but they usually can’t receive a transplant even if they need it.

LaVarne Burton, president of the American Kidney Fund, explains the twofold challenge with living donation. Of the 92,000 Americans on the kidney transplant list, roughly 27,000 are Black Americans. Most will receive a kidney transplant from deceased donors.

An organ from a living donor is better, but transplanting it entails significant social and financial risks for donors. For example, living donors may face insurance denials, higher premiums for life, disability, and long-term care insurance, and there are no federal protections against job loss from a donation-related leave.

In July, Congress passed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” a sprawling tax measure that reaches deep into the nation’s social and environmental safety nets, including reshaping programs like Medicaid and Medicare. The Center for American Progress estimates that the law will result in $490 billion in cuts to Medicare from 2027 to 2034. About 60% of adult kidney transplant recipients rely on Medicare coverage.

“Throughout our existence, we’ve worked with every administration and every political party,” Burton says. “We’re dealing with life and death here. People who are in kidney failure are at a very high risk of dying. We want to do everything we can to make sure they have access to care.”

10. What kind of government oversight does the organ donation and transplant system have?

The Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, oversees multiple organizations that oversee the organ donation and transplantation system. These include the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which oversees OPOs.

HHS also oversees the Health Resources and Services Administration which oversees the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. OPTN operates under a federal contract managed by UNOS.

As a result, UNOS enforces oversight through a peer review process managed by the Membership and Professional Standard Committee. The committee reviews applications for membership in OPTN, reviews identified risks to patient safety, and evaluates OPTN members by providing feedback and recommendations to improve performance, compliance, and quality.

“This area of health care has an extreme amount of oversight,” says Glazier, who previously served as a committee member on the MPSC board. “It’s still a human process, so it’s never going to be perfect, but compared to other parts of our medical system, there is a lot of oversight.”