This article is part of “On Borrowed Time,” a series by Anissa Durham that examines the people, policies, and systems that hurt or help Black patients in need of an organ transplant.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, Craig Merritt asked himself the same two-word question:

Why me?

Trapped in a dialysis chair for four hours at a time, he’d watch his blood be removed, cleaned, and recirculated back into his body. After three years of this routine he started to wonder: Will I ever get a kidney transplant? Or will I die waiting for one?

“I believe there are good spirits and demonic spirits. I wrestled and dealt with demonic spirits,” he says. “The thought of suicide came. Taking myself out.”

At an arm’s length away from him sat other, oftentimes Black, dialysis patients. Within earshot of everyone’s medical history, he became familiar with the other regulars. Merritt remembers one young Black man in his 30s who would come in with a bag of gas station snacks. Chili cheese fries and Hawaiian Punch. At one point, Merritt offered the man living with diabetes $50 to lower his levels of phosphorus by two points. The mineral can be elevated in people with kidney disease, leading to increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

“His eyes got big. We shook on it,” he says. “He couldn’t do it. He didn’t do it.”

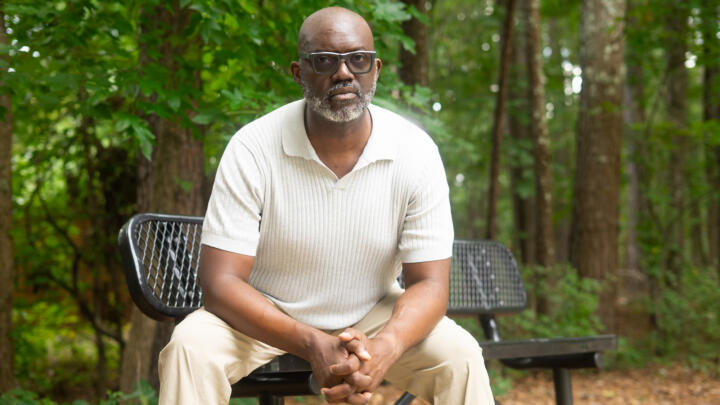

Credit:Rita Harper for Word In Black

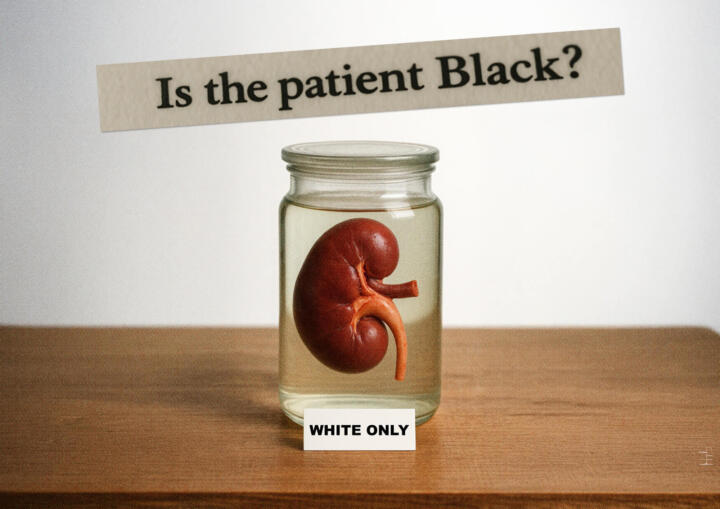

What Merritt didn’t know at the time was that the system was stacked against him. A medical calculation made it harder for Black patients like him to get on the kidney transplant waitlist.

How common are race-adjusted clinical algorithms?

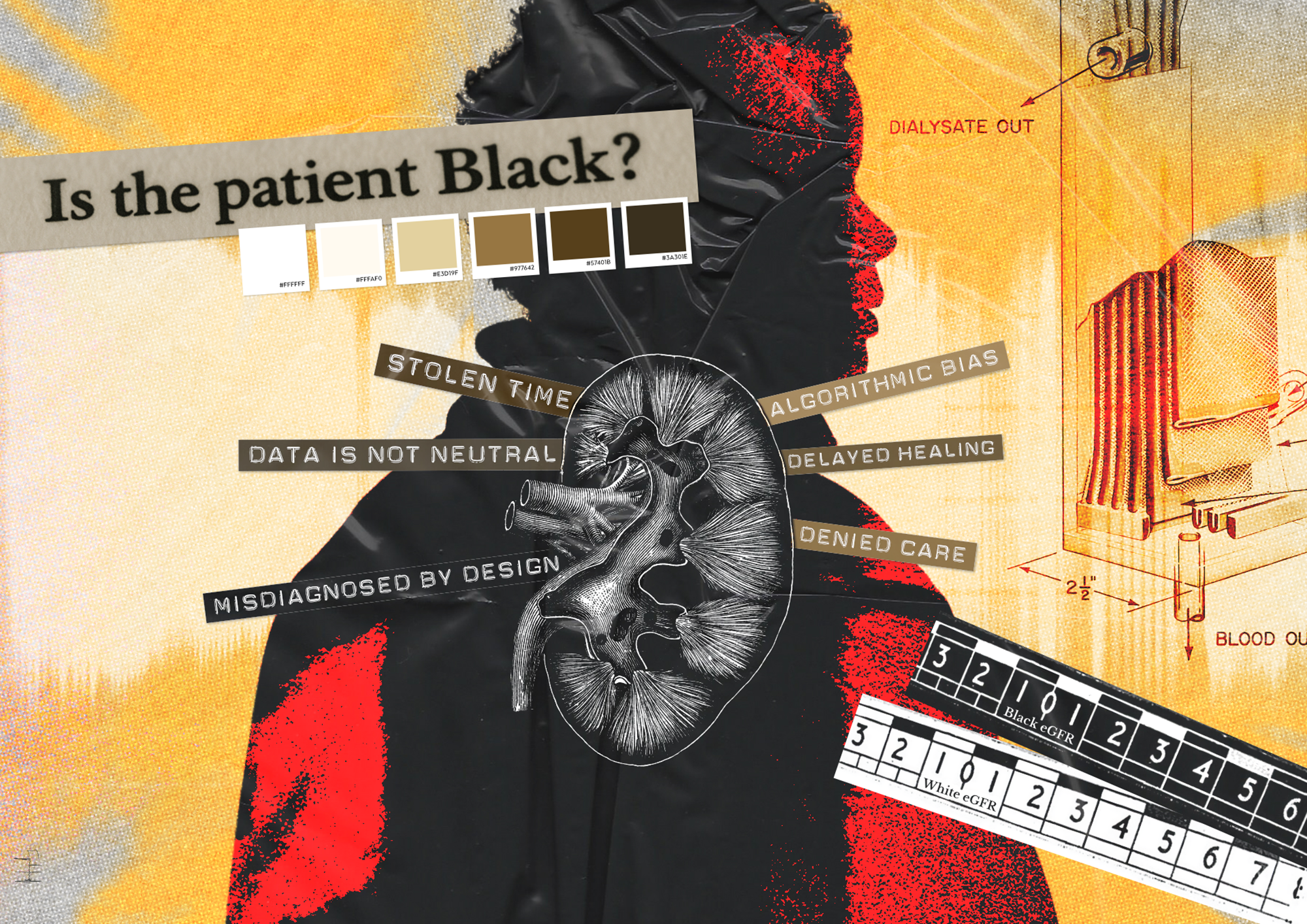

The eGFR, or estimated glomerular filtration rate, is an equation that estimates the percentage of kidney function someone has — based on how well kidneys filter waste products from blood. For Black people, doctors would increase the value by a few points, simply based on race. This delayed the point at which doctors would say their kidneys had failed. Meaning, by the time Black folks got on the transplant list, many either died on dialysis or their body was too weak to survive a kidney transplant.

Currently, there are about 92,000 Americans on the kidney transplant list, and roughly 27,000 are Black Americans. For decades, this race-based calculation exaggerated Black patients’ kidney function, making it take longer for them to get on the transplant list. Experts say it’s best to be referred for transplant as early as possible and ideally before you start dialysis. The longer you are on dialysis, the quicker your body deteriorates.

The eGFR is among scores of clinical algorithms with race-based adjustments; as of March 2025, there are 42 risk calculators, 15 medications, five medical devices, five lab test results, and one therapy recommendation that still use race and ethnicity to some capacity in medical decision making. These include a common lung function test that, by changing expected lung capacity for Black people, makes it more difficult to get on the transplant waitlist.

There are people out there who will probably never know this happened to them.

Jazmin Evans

There has been some retreat from these sorts of algorithms. In July 2022, for example, the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, prohibited transplant hospitals from using race-based eGFR calculations. In January 2023, UNOS required all transplant programs to review their waiting lists and modify the wait time for Black patients affected by the race-based eGFR. And there has been a race-free version of the vaginal birth calculator available since 2021.

But many physicians and hospital systems are fighting to keep race-adjusted algorithms.

“A lot of these tools were done as a well-intentioned progressive effort to do well by Black patients, in the spirit of personalized medicine,” says David Jones, a trained psychiatrist and the A. Bernard Ackerman, professor of the Culture of Medicine at Harvard University. “This was seen as a progressive pro-race justice thing to do. What people didn’t do carefully enough was to see how these tools actually operated.”

‘I got Black kidneys’

In 2000, Merritt, then 29, went in for a routine doctor’s appointment. The cold winter air was fading into spring. He was congested. The nurse took his vitals. His blood pressure was high. The doctor referred him to a nephrologist. After a biopsy, doctors diagnosed him with stage 3 FSGS kidney failure, a rare type of kidney disease that causes scarring. It was shocking.

That’s when Merritt realized his stressful job and high sodium intake didn’t help with his kidney health. The stress led to chronic headaches and migraines. To cope, he took non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and BC powders religiously. He started popping pills to stop headaches before they could start.

He credits his proactive nephrologist — a doctor who specializes in the care of kidneys — for teaching him how to read his labs. Each appointment was like a medical school class. One test kept drawing his attention — the eGFR.

“That always raised a flag for me,” he says. “So, we’re different from the rest of the world? I got Black kidneys, and everybody else got white kidneys. It never set well with me.”

The only explanation doctors gave him was that it was just the calculation. For 18 years, Merritt maintained his kidney function. But as he got older, so did his kidneys. His longtime nephrologist, or kidney specialist, set up his transplant evaluation at Emory University Hospital. By the time he got listed, he was in end-stage renal disease. Then, the nephrologist, whom he thought of as an aunt, died of a brain aneurysm.

“What am I gonna do?” he says. “Who’s gonna care for me like she did?”

And then a month later, in September 2018, came dialysis.

Embedding racism in medicine

Clinical algorithms are tools that help health care providers make decisions. They provide a methodical approach to diagnose, treat, and manage different medical conditions. Doctors use them for everything from calculating your body mass index to evaluating your risk for heart disease.

Algorithms can be packaged in a calculator, a flowchart, or an AI model. There are hundreds of clinical algorithms in medicine. But not all include race and ethnicity. Dozens of algorithms still in use include race as a factor. The idea behind considering race is roughly to improve health care. But poor science and racism have led to the development and misuse of algorithms.

There’s a different issue with every algorithm, Jones says, but at the core is the idea that there are two types of humans: Black humans and white humans — and that there are biological differences between the two. This false belief that race is a scientific, not social, construct got its start in the U.S. during slavery, when white people needed a justification for their dehumanizing enslavement of Africans. And the foundation of modern medicine was partially centered on experiments performed on enslaved African Americans.

Any medical algorithm or other “clinical tool that relies on that Black-white dichotomy is in trouble, because there’s no scientific way to defend that,” Jones says.

A 2023 workshop examining race-based clinical algorithms highlighted the historical roots of this thinking. A book on the workshop’s proceedings notes that “Scientists even used supposed anatomical differences across races to rank the relative value of each race, with White people at the top of this ranking and Black people at the bottom.”

For example, in 1851, a prominent physician, Samuel Cartwright, promoted the idea that slavery was justified because Black people had a lower lung capacity than white people. The way to cure it? Performing unpaid strenuous labor for white people, until death.

Why did it take years to change a flawed algorithm?

Clinical algorithms with race adjustments like eGFR, lung function test, and the vaginal birth after cesarean calculator, which largely affected Black patient outcomes, prevailed in medicine for decades. Toni Eyssallenne, deputy chief medical officer at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, says many of these tools are not based on real research or thorough science. But doctors have known this for years.

In 2022, Eyssallenne joined the Coalition to End Racism and Clinical Algorithms, or CERCA, shortly after it formed and after the NYC Board of Health declared racism a public health crisis. The coalition brings together physicians, nurses, researchers, and community health workers. The goal isn’t to eliminate race from the conversation — it’s to be race-conscious.

“Every single algorithm took years and years and years of advocacy,” she says. “CERCA joined those fights.”

As a medical student, Eyssallenne remembers professors teaching that there is a biological difference between Black and white people. They told med students race-based tools were necessary because Black people die more often from heart disease, hypertension, strokes, and the like. This was part of the justification for these racial adjustments in algorithms and throughout medicine. Exam questions reinforced race essentialist thinking, she says. If medical students raised a red flag or said they don’t do race-based medicine, they failed their classes.

“Even as a Black female physician, I’m complicit, because I’ve learned to do the same thing,” Eyssallenne says. “But now that you know, let’s do it differently.” The medical establishment is a little bit defensive, she says. “Nobody wants to feel like they’re doing something inequitable on purpose. It comes down to the way we are teaching.”

Eyssallenne says recognizing an algorithm is harmful is only the first step. Changing one requires experts to recommend and implement new guidelines — a process that can take a decade or more. CERCA formed to speed up that time. One of the main arguments she hears from doctors about not changing race-based tools is a desire to not cause harm. Yet the harm already exists. The scientific rigor researchers require to prove the necessity of removing race adjustments was never applied when these tools were created in the first place.

I saw death at these centers — people dying on (dialysis) machines.

Craig Merritt

The intention behind race- based tools is somewhat complicated, Jones, the Harvard professor, says. Most of these race- corrected tools were introduced in the 1990s, after the National Institutes of Health required the collection and reporting of demographic racial data in funded research projects. As a result, this led to the development of algorithms that use race as a substitute for genetic difference. The eGFR race factor was based on superficial research that showed higher creatinine levels in Black patients which were attributed to Black people having higher muscle mass.

“If these tools, if used as directed, were to make things worse for Black people, then the tool creators were racist. There’s no way you can wiggle your way out of that responsibility,” Jones says. “Some seem like reasonable people who didn’t think hard enough about what they were doing. But does that exonerate you, or does that implicate you?”

But there’s still some back and forth about other common tests. A spirometry test measures how well your lungs function, and it still uses a race-based correction. The adjustment reduces the lung capacity for Black folks by 10-15% and Asians by 4-6%. This race adjustment contributes to the underdiagnosis of lung disease and makes it more challenging to get on the lung transplant waitlist. The American Thoracic Society solely endorses a race-free equation known as GLI-Global, but it’s only a recommendation.

“It doesn’t make sense. It’s us not trying to address the root cause of the issue. The structures we built this country and medicine on are inequitable structures. We have to reckon with that,” Eyssallenne says. “That’s why it takes so long. It’s so deeply embedded.”

Will I ever get a kidney?

Once you’re on dialysis, there’s no getting off.

In 2012, during her senior year of high school, 18-year-old Jazmin Evans decided to try out for the dance team. To qualify, her school required a physical exam. She didn’t give the exam a second thought. But then, her primary care physician found protein in her urine. Something wasn’t right.

A nephrologist broke the news: stage 3 FSGS kidney disease. Without even knowing it, Evans’ right kidney hadn’t fully developed, leaving both kidneys damaged.

Fast forward to 2019, Evans now 25, started a doctorate in Africology and African American Studies at Temple University — and dialysis. Every night, she connected to the peritoneal dialysis machine beside her bed. The steady hum of white noise from the machine helped her fall asleep. That nightly, eight-hour routine went on for years.

Evans’ adjusted eGFR calculation delayed both the start of her dialysis treatment and her placement on the transplant list. If race hadn’t been factored into the calculation, she would’ve been placed on the list years earlier.

“What I went through, I don’t wish that on many people. It was not fun,” she says. “There are people out there who will probably never know this happened to them.”

After four years on dialysis, in March 2023, Evans received a letter in the mail from the United Network of Organ Sharing. It revealed that throughout the course of her kidney disease care, doctors used a race-based tool that automatically adjusted her eGFR score for kidney function. “I was angry — to say I was very upset is an understatement,” she says.

To correct the unethical and unjustified calculation, the hospital credited Evans with extra years of wait time, raising her total time on the transplant waitlist to about 8 years. This moved her higher on the transplant list.

On July 4, 2023, Evans got her kidney transplant.

Where does race-based medicine stand?

In 2017, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, was the first hospital to drop the eGFR race correction. Three years later, in 2020, Jones co-wrote a paper alongside his students addressing the use of race corrections in clinical algorithms. He and his coauthors looked at race corrections in cardiology, nephrology, obstetrics, and urology — all disproportionately impacting Black patients. And they illustrated how these race-based tools contribute to bias in medicine and resources being directed to non-Black patients.

Shortly after publication, multiple hospitals dropped the race-based eGFR modifier. The following year, the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommended removing race from eGFR calculations. UNOS then instituted its race-based eGFR ban followed by its mandate to review waiting lists for impacted Black patients.

Dr. Pooja Singh, division director for nephrology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, says roughly 49-65% of patients at hospitals in its health system — Jefferson University Hospital and Jefferson Einstein Hospital — are Black. Between the two hospitals, Singh and her team adjusted the accrued wait time for 405 patients. As a result, 122 patients have received kidney transplants sooner because of the newly credited wait time.

“They would have been transplanted, don’t get me wrong, but it’s possible they would have been transplanted a year or two years later,” she says. “But they’ve been transplanted earlier as a result of adjusting the eGFR calculation.

The lives lost due to this algorithm

Every dialysis visit, Merritt had a goal: stay under the radar. He never wanted the doctors to have to spend time with him. Inside the dialysis center, morale was low. He watched fellow patients disappear from the chairs beside him — never knowing if they’d transferred, or died.

“I saw death at these centers — people dying on the machines,” he says.

At this point, Merritt was listed on three different transplant lists and working on the fourth. 2023 marked his fourth year on dialysis. That’s when doctors found a small mass on one of his kidneys. Around the same time, he gets a letter in the mail from the University of Alabama, Birmingham informing him that UNOS had changed its policy.

Six months later, doctors checked the mass again. It was cancer. On July 6, 2023, they removed his right kidney. It wasn’t until November 3 that the Medical University of South Carolina, another hospital where Merritt was listed, told him his credited wait time had doubled.

A few days later, on a Sunday evening, he got the call. It was surreal. Finally, it was a kidney. On November 6, 2023, he got his transplant.

“Think about how many brothers and sisters, uncles, aunties, moms, dads, grandmothers, grandfathers that should have had a kidney or placed on dialysis a lot sooner,” Merritt says. “What the system was saying is you guys aren’t worth the organ. You’re not worth it to our medical system.”

As of publication, no database tracks the number of Black patients who died before getting on the kidney transplant waitlist — or died while waiting on the list — because of the race-based eGFR correction.

Anissa Durham reported this story as one of the 2025 U.S. Health System Reporting fellows supported by the Association of Health Care Journalists and the Commonwealth Fund. The Commonwealth Fund also supports Word In Black’s health reporting.