The Dating Apps Reporting Project is an 18-month investigation. It was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network and The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, and copublished with The Guardian and The 19th.

When a young woman in Denver met up with a smiling cardiologist she matched with on the dating app Hinge, she had no way of knowing that the company behind the app had already received reports from two other women who accused him of rape.

She met the 34-year-old doctor with green eyes and thinning hair at Highland Tap & Burger, a sports bar in a trendy neighborhood. It went well enough that she accepted an invitation to go back to his apartment. As she emerged from his bathroom, he handed her a tequila soda.

What transpired over the next 24 hours, according to court testimony, reads like every person’s dating app nightmare.

After sipping the drink, the woman started to lose control. Her memory blurred. She fell to the ground, and the man started to film her. He put her in a headlock, kissing her forehead; she struggled to free herself but managed to grab her things and leave. He followed her out the door, holding her shoes and trying to force her back inside, but she was able to call an Uber, vomiting in the car on the way home.

She woke up at home, soaking wet on her bathroom floor, the key to her house still in her door. She continued vomiting for hours. When she came to, she reported the assault to Hinge.

Hinge is one of more than a dozen dating apps owned by Match Group. The $8.5 billion global conglomerate also owns brands like Tinder (the world’s most popular dating app), OkCupid, and Plenty of Fish. Match Group controls half of the world’s online dating market, operates in 190 countries, and facilitates meetups for millions of people.

Match Group’s official safety policy states that when a user is reported for assault, “all accounts found that are associated with that user will be banned from our platforms.”

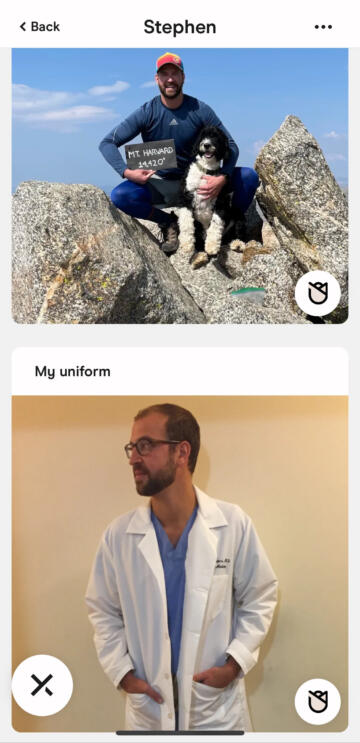

So why, on the night of Jan. 25, 2023, was Stephen Matthews still on the app? Just four days before, Match Group had been alerted when another woman reported him for rape. A little more than a week later, he was reported for rape again. This time, the survivor went to the police.

None of these women knew that the company had known about his violent behavior for years. He was first reported on Sept. 28, 2020. By then, Match Group’s safety policy was already in place.

Even after a police report, it took nearly two months for Matthews to be arrested — the only thing that got him off the apps. By then, at least 15 women would eventually report that Matthews had raped or drugged them. Nearly every one of them had met him on dating apps run by Match Group.

On Oct. 25, 2024, a Denver judge sentenced Matthews to 158 years to life in prison after a jury convicted him of 35 counts related to drugging and sexually assaulting eight women, drugging two women, and assaulting one more for a total of 11 women. Attorneys for the women said much of that violence could have been prevented.

“It is shocking that for years after receiving reports of sexual assault, Hinge continued to allow Stephen Matthews access to its platforms and actively facilitated his abuse,” said Laura Wolf, the attorney representing the woman whose police report led to the arrest. Following best practices for reporting on sexual assault, the Dating Apps Reporting Project is honoring survivors’ requests for anonymity. Matthews’ attorney, Douglas Cohen, declined to comment. A letter that The Dating Apps Reporting Project sent directly to Matthews in jail went unanswered.

Match Group’s reach is so massive — its mission is “to spark meaningful connections for every single person worldwide” — that people are more likely to meet through its apps than out at the bars, at church, or through friends.

But Matthews’ case shows that even as these apps have made it easier for us to connect with a seemingly endless pool of potential lovers, they have also made it easier for people who commit sexual abuse to reach a seemingly endless number of potential targets.

In 2022, a team of researchers at Brigham Young University published an analysis of hundreds of sexual assaults in Utah. They found attacks facilitated by dating apps happened faster and were more violent than when the perpetrator met the victim through other means. They also found that perpetrators who use dating apps are more likely to target vulnerable people. Almost 60 percent of sexual assault survivors self-reported a mental illness.

Match Group has known for years which users have been reported for drugging, assaulting, or raping their dates since at least 2016, according to internal company documents. Since 2019, Match Group’s central database has recorded every user reported for rape and assault across its entire suite of apps; by 2022, the system, known as Sentinel, was collecting hundreds of troubling incidents every week, company insiders say.

Match Group promised in 2020 that it would release what’s known as a transparency report — a public document that would reveal data on harm occurring on and off its platforms. If the public were aware of the scale of rape and assault on Match Group apps, they would be able to accurately assess their risk. As of February 2025, the report has not been released.

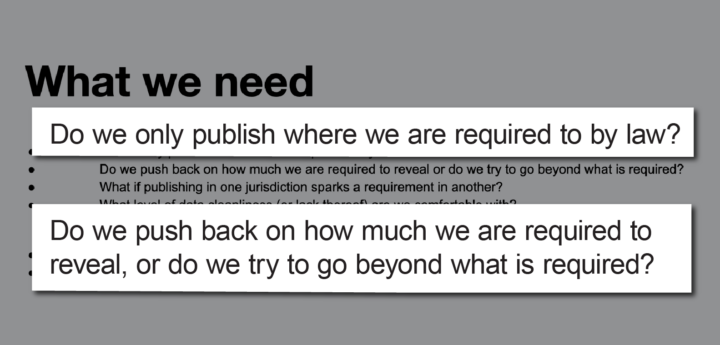

Instead, as people continued to get hurt, the company dithered over what damning information should be hidden. “Do we only publish where we are required by law?” reads a slide in a 2021 presentation shown multiple times to Match Group employees as well as external safety partners. “Do we push back on how much we are required to reveal, or do we try to go beyond what is required?”

No online space is risk-free. But while Match Group has long possessed the tools, financial resources, and investigative procedures necessary to make it harder for bad actors to resurface, internal documents show the company has resisted efforts to spread them across its apps, in part because safety protocols could stall corporate growth.

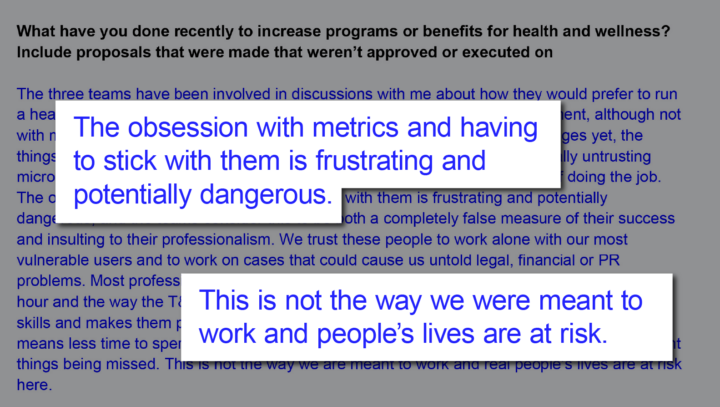

“The obsession with metrics and having to stick with them is frustrating and potentially dangerous,” one employee wrote in 2021 after the company learned that the investigative news nonprofit ProPublica was planning a story. “This is not the way we were meant to work and people’s lives are at risk.”

The same person asked their superiors: “‘How much would you personally pay to stop just one person being sexually assaulted by a date, one child being trafficked or one vulnerable person being driven to suicide by a predator?’ I feel that if I asked members of our staff that question individually, they would put a high value of their own money on it – But as a group nobody is ready to hear that yet.”

Since 2021, Match Group has publicly promised to improve the safety of their products and share data, but company insiders say safety has not improved. A brief hiring spree sparked by congressional and media scrutiny has been largely scaled back, according to former employees. In 2024, the remaining employees from the central trust-and-safety team Match Group set up in response to increased scrutiny were let go and their jobs outsourced to overseas contractors. Facing pressure from Wall Street, Match Group removed CEO Bernard Kim in early February 2025 as he struggled to cut costs and end the steady decline in subscribers to Match Group’s most powerful app, Tinder.

Members of Congress have repeatedly requested data from Match Group on sexual harm. In February 2020, 11 members of Congress wrote to then-CEO Shar Dubey asking for details on how the company responds to reports of sexual violence. In July 2023, two Democrats, then-Rep. Annie Kuster of New Hampshire and Rep. Jan Schakowsky of Illinois followed up after we inquired on the status of their efforts. The company has still not provided the data.

In September 2024, the House of Representatives passed a bill that requires consumers to be notified if they have interacted with a user on a dating app who has been banned for defrauding consumers of money or personal financial information. But the bill stopped short of addressing the issue of sexual assault on the apps, and it died in the Senate.

Our review of hundreds of pages of internal company documents, along with thousands of pages of court records, securities filings, and analyst reports, coupled with dozens of interviews with current and former employees and survivors of sexual violence found women who report being raped get no traction, while accused rapists like Stephen Matthews keep swiping — and assaulting.

Our own testing on Match Group apps shows that as of February 2025, not much has changed. Banned Tinder users, including those reported for sexual assault, can easily rejoin or move to another Match Group dating app, all while keeping most of their key personal information exactly the same.

The Dating Apps Reporting Project sent Match Group a four-page letter detailing our findings. The company responded with a short statement. The statement did not dispute that Match Group has carefully documented the extent of harm on company apps for years without sharing that information with the public. It also defended the company’s efforts to make platforms safe.

“We recognize our role in fostering safer communities and promoting authentic and respectful connections worldwide,” the statement provided by Kayla Whaling, senior director of communications, read. “We will always work to invest in and improve our systems, and search for ways to help our users stay safe, both online and when they connect in real life.”

The company said it vigorously combats violence. “We take every report of misconduct seriously, and vigilantly remove and block accounts that have violated our rules regarding this behavior,” its statement read. Our own testing found otherwise.

Starting in April 2024, The Dating Apps Reporting Project created a series of Tinder accounts that we subsequently reported for sexual assault. Soon after, Tinder banned the accounts, and we started investigating how easy it would be for a banned user to create new accounts.

Repeatedly, we found that users, soon after being banned, could create new Tinder accounts with the exact same name, birthday, and profile photos used on their banned accounts. Users banned from Tinder were also able to sign up for Hinge, OkCupid, and Plenty of Fish without changing those personal details.

To get around the Tinder ban, we used techniques commonly suggested by online guides and forums that don’t require lots of technical knowledge to understand. We were able to verify three techniques that allowed banned Match Group users to repeatedly bypass being flagged when creating new accounts.

In its statement, Match Group cast itself as an industry leader in deploying technology to promote safety, including “harassment-preventing AI tools, ID verification for profiles, and a portal that helps us better support and communicate with law enforcement investigating crimes. … Every person deserves safe and respectful experiences. We are committed to doing the work to make dating safer on our platforms and beyond,” the statement said.

Sept. 28, 2020 — the date Denver cardiologist Stephen Matthews raped a woman who reported him to Hinge — is also the date Tracey Breeden was brought on as Match Group’s head of safety and social advocacy.

Breeden was a flashy hire. “With Tracey coming on board, we are reaffirming our commitment not just to be safety leaders in the dating space, but across the entire tech sector,” then-CEO Shar Dubey said.

Sporting a trademark black leather jacket and short, slick-backed hair, Breeden went by the nickname “Tornado” during her 15-year career in law enforcement. What made her attractive to Match Group was her most recent job at Uber. She helped the global ride-hailing company revive its reputation after a series of scandals — from persistent reports of harassment of women employees to allegations that it was ignoring sexual assault that occurred during Uber rides.

Working for an Algorithm

When Drivers Are Attacked, Uber Leaves Police Waiting for Help

An investigation by The Markup found that Uber is slow to respond to law enforcement requests, leaving drivers vulnerable to repeated attacks

Breeden spearheaded a safety report in 2019 that told the public what Uber knew about nearly every problem, including nationwide reports of intoxicated drivers, traffic fatalities, and incidents of sexual violence. The report became a key metric of success for the company.

In hiring Breeden, Match Group hoped to replicate this success across its portfolio of apps. “Corporations,” she said in a press release announcing her arrival, “have a responsibility to help ensure safe experiences for their users.”

Breeden’s team garnered public attention for its new safety measures, including partnerships with NGOs, optional AI-assisted photo verification, and a law enforcement portal where police and prosecutors can request data.

She also fostered a partnership with Garbo, a startup that offered low-cost background checks. It launched on Tinder in 2022. Experts point out that background checks are not always reliable as they pull from outdated databases, and research suggests that most people who commit sexual abuse do not encounter the criminal justice system. For example, Matthews had no criminal record.

During this time, Match Group invested $100 million into safety as a recurring cost, the company said, and boasted about Breeden’s “central safety team.”

Her team of veteran safety professionals referred to themselves as “The Avengers,” even donning superhero costumes at company events.

But Michael Lawrie called this “safety theater.”

Lawrie worked for Match Group for nearly a decade, shaping and leading a safety team for one of the company’s smaller brands, OkCupid. Sometimes working 80-hour weeks, he spent hours, even days, sniffing out savvy users who tried to thwart bans by creating multiple accounts.

Over a 30-year career in content moderation, Lawrie said, he saw many users like Stephen Matthews. “You’re dealing with one repeat offender. I’ve dealt with god knows how many repeat offenders,” he said.

A yellow Post-it note on the side of Lawrie’s computer listed out some of his responsibilities: “Rape flags. … Investigate miscreants.”

These days, Lawrie is trying to start an advocacy organization for content moderators and other front-line safety workers. But, he said, he’s done with dating apps.

“I don’t think they’re safe enough at the moment,” he said. “They’re gonna get worse. …I’m hoping dating sites vanish.”

Lawrie said he was initially excited about Breeden’s hire. He said she spent her first few months on the job talking to each brand’s safety team, and told him that she was “very impressed” by the work OkCupid was doing.

Each of Match Group’s biggest apps provided their self-described strengths and weaknesses to Breeden’s team, according to an internal spreadsheet. At Hinge, these weaknesses included a “very rudimentary warning system with no targeted comms and no follow through” and “no way to find” the original profile “of a bad actor who has created multiple profiles.”

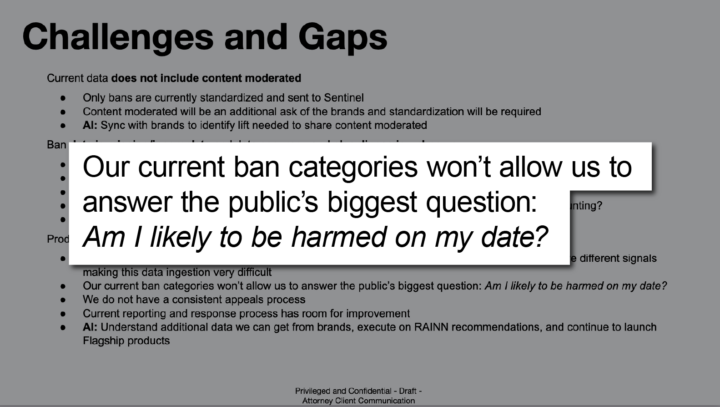

Breeden was confronted with an existential problem. “Our current ban categories won’t allow us to answer the public’s biggest question: Am I likely to be harmed on my date?” reads a slide in a presentation drafted by her team in April 2021. While each of Match Group’s apps had a system of reporting and banning violent users, the information was disorganized, and none of the apps talked to each other.

Lawrie hoped Breeden would improve safety at the company. But he quickly grew frustrated that neither she nor Match Group leadership listened to his pleas for what they really needed to make platforms safer: To hire trained — and expensive — investigators and integrate powerful moderation tools across all the apps.

OkCupid already had those tools. Lawrie was using them every day.

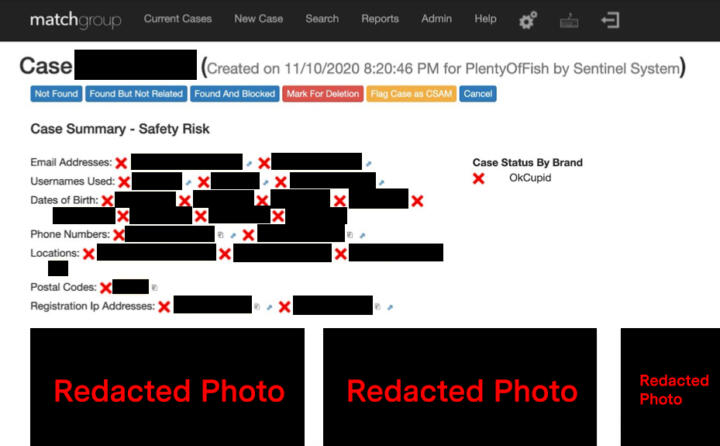

One of those was the Sentinel system, which had been up and running across Match Group’s apps for at least five years before Breeden arrived. It works like this: When a user is banned for something serious — like sexual assault — a case is created in Sentinel with the phone number and email address associated with their account. In interviews, multiple current and former employees described how those reports circulate through each of Match Group’s apps. The system is designed to ban anyone who uses that information. It also grabs the original profile’s IP addresses, photos, and birthdate.

Such a system seems robust at first glance — but none of the Match Group’s apps require users to provide photo identification (the kind needed to buy alcohol or board an airplane), so once a person is kicked out, they can easily start a new account with different contact information. A quick search yields scores of online forums with clear steps and suggestions for how to rejoin the apps. In addition, internal company documents show information on IP addresses, photos, and birthdate were not used to ban a user if they appear on another Match dating app.

Lawrie’s team at OkCupid knew Sentinel could only do so much.

So his team deployed other tools to fix its shortcomings, including one that could automatically ban a profile that was linked to a phone number, photo, or URL that had been previously banned — even if the user made an account with a different email or IP address. This tool was designed to be proactive rather than reactive, so that the profiles of alleged perpetrators like Matthews would not resurface after they had been reported.

Internal company documents from 2019 and 2020 show thousands of reports of “serious physical assault,” abuse, or violence on OkCupid that were deemed serious enough to get users banned from all of Match Group’s apps. This is among the information the company kept from the public.

Breeden and Match Group leadership praised Lawrie and his team at OkCupid, he said, for their thorough investigative work and for handling some of the company’s most difficult cases. Yet, he said, Match Group never built out a skilled, experienced investigative unit at other brands like the one he headed up at OkCupid. Under Breeden’s leadership, he said, they faced pressure to speed up investigations and train outsourced labor to use complicated moderation tools.

A week after a damning article in 2021 revealed that content moderators with little training were asked to rapidly deal with violent sexual content across Match Group’s brands, then-CEO Dubey sent out an all-staff email addressing the controversy. She CC’d Breeden, acknowledging that the brand’s safety teams were not all on equal footing.

As Match Group prepared internally for the story to break, Lawrie was asked to write a report for Breeden outlining his team’s accomplishments “to make sure when Tracey describes and acknowledges what you are doing individually to celebrate the good work that you are doing.”

Lawrie used that report to protest.

“Most professionals aren’t judged on how many cases they can hurry through in an hour,” he wrote. The way Match Group expects its trust-and-safety and support teams to work “basically diminishes their skills and makes them production-line workers.” Breeden declined to comment for this story, citing a nondisclosure agreement.

Lawrie left the company in 2022 and said most of his small team that was ferreting out malicious users also left due to a negative workplace environment. He said much of their work was outsourced to contractors with little training and severe quotas.

He now cautions anyone using a dating app to understand that they’re not in the business of protecting users.

“You’re on your own pretty much,” he said.

As Lawrie was getting pushed out of Match Group, Matthews kept appearing on the company’s apps.

One crisp fall evening in 2022, one of the Denver cardiologist’s old medical school classmates was on Hinge when her phone screen filled up with a familiar face.

Matthews was being promoted on the app as a Standout, a popular profile that Hinge’s algorithm thinks you’ll like. To match with a Standout, users must send the person a rose. They get one free rose a week, but they cost $3.99 a pop after that. His classmate did not send Matthews a rose.

By this point, Matthews had already been reported for rape at least once to Hinge. Court documents show that he had already allegedly sexually assaulted nine women and drugged 10. Not only did the apps allow him back on, they featured Matthews’ profile.

As the COVID-19 pandemic dragged on, people got tired of forking money over for dating apps. Match Group still made a hefty profit, but its growth flatlined. Its stock cratered, losing nearly half its value between October 2021 and April 2022. That month, an analyst from J.P. Morgan wrote that the firm had received more messages about “the underperformance of MTCH shares in recent weeks than any other topic.”

In May 2022, Match ousted Dubey and installed Bernard Kim as CEO, a former executive at the gaming company Zynga that popularized viral games like “FarmVille.”

While Dubey spoke frequently about trust and safety and worked closely with Breeden, Kim hardly mentioned safety when he began his time at Match Group, instead emphasizing the need for continued rapid expansion to drive long-term shareholder value.

Lawrie said that Kim, with his background in gaming rather than dating apps, had no interest in love. “He just wants to make money. He’s just there to increase profits,” Lawrie said. “If he’s looking at a bottom line, then it’s easier to have a lawsuit than it is to provide safety. I know which one he’s gonna pick.” Match Group declined to make Bernard Kim available for an interview. Messages sent to Kim directly went unreturned.

While the tension between growth and safety exists across the tech sector, it is especially high at dating apps companies where executives have to worry about constant churn — users leaving the apps when they are no longer looking for dates. Every time Match Group delivers on its promise, it also loses customers.

In February 2024, six dating app users filed what they hope will be certified as a class action lawsuit. They argue Match Group uses “addictive” features to encourage compulsive use while not leading to any real increase in off-app relationships. “The app is designed specifically to hook them, and to keep them paying subscription fees — not to help them find love,” attorney Ryan Clarkson said. Match Group filed to dismiss the lawsuit in September, noting in its quarterly report that it “will defend vigorously” against the allegations.

Despite Kim’s efforts, Match Group’s stock price continued to drop, and during that time, so did any mention of trust and safety. In over a year of quarterly investor calls, Kim only referenced safety efforts once.

Employees who pushed for these initiatives were forced out or laid off, including Breeden — a leader who was so convinced of her own invincibility that she showed up to an event wielding a Captain America shield.

Match Group fired its power hire in October 2022. Layoffs hit her team over the next several months. In February 2024, the remaining critical investigators and law enforcement liaisons on Breeden’s central safety team were shown the door.

Lawrie said group chats of former Match Group employees have been gossipping about the cutbacks.

“You’re not gonna see them taking safety seriously ever again,” he said, adding that the only thing that he thinks might change that is legislation.

Four months before Matthews was arrested, a post on a Facebook group in Denver blew up, right around Christmas.

Over and over again, women furiously detailed negative experiences they or their friends had with Matthews.

Some women described him as “sketchy.” Others called him “terrible” and “not safe.” Multiple women told a similar, dark story: that they were offered drinks, blacked out, and sexually assaulted.

The thread reached 150 comments. Two women wrote the same thing: that they had been waiting for someone to post about the cardiologist.

The flood of Facebook comments mirrored details in the police reports released the following year. Nearly all of the 16 women included in the district attorney’s initial complaints were offered tequila. Eight recalled playing Jenga. Six mentioned a hot tub.

As these stories circulated in this small corner of the internet in December 2022, the Denver cardiologist stayed on Match Group apps.

Those fortunate enough to know about the Facebook group — and who had the foresight to check for Matthews on it — would be saved from a bad date or worse. But the fact that he could still log into Tinder and Hinge left him with a pool of thousands of unsuspecting women whom he could — and would — continue to match with.

The Dating Apps Reporting Project is aware of four additional women who have accused Matthews of drugging and/or raping them who were not part of the criminal complaint. Each of these women met Matthews on a Match Group app during a single year between the summers of 2020 and 2021.

During the years Matthews was on their apps, Match Group hired and fired Breeden. It made loud promises on sexual violence, announced initiatives and product lines, and promised a transparency report. But it was not straight with the public, which meant the women matching with Matthews on Match Group apps were not aware of the risk they faced.

Match Group’s partnership with Garbo, the background check company, also fell apart in the summer of 2023. “It’s become clear that most online platforms aren’t legitimately committed to trust and safety for their users,” Garbo wrote in a searing blog post.

After spending so much energy talking about monetization, gamification, and growth, Kim began to publicly acknowledge this problem. Speaking at the Citibank conference in the fall of 2023, he said the company was investing in new features to make sure “women have a good experience while they’re in the product. They feel safe. They feel secure. Etc.”

Privacy

Car Tracking Can Enable Domestic Abuse. Turning It Off Is Easier Said Than Done

Internet-connected cars allow abusers to track domestic violence survivors after they leave

The “etc.” does not seem to include increased transparency about safety. Instead, in May 2023, Tinder released a “female-focused package,” a curated list of “high-quality profiles.” It is unclear how Tinder determines these high-quality matches. Hinge’s Standout feature, which is similar, had previously promoted Matthews.

In fact, under Kim’s leadership, all mentions of a transparency report disappeared from the company’s annual impact report. Ironically, this was around the same time that new legislation in Europe required tech companies to disclose reports of “non-consensual behavior” and other issues. Match Group will be required to submit a transparency report to the European Union on the scope of harm on their platforms later this month. Lawmakers in India and Australia are also demanding transparency.

This is exactly the situation Breeden and her team pondered three years ago. “What if publishing in one jurisdiction sparks a requirement in another?” read a slide in the same internal presentation where Match Group’s trust-and-safety leaders wondered whether they should “push back on how much [they] are required to reveal.”

After Match Group published a disappointing earnings report in February 2025 that fell below analysts’ expectations, it also announced that Kim would be replaced by former Zillow CEO Spencer Rascoff. Tinder’s revenue, sales, and subscribers had all gone down.

As Match Group struggles to reverse its decline, it’s also aware that its reputation is in the spotlight. Earnings calls and shareholder letters over the first three quarters of 2024 indicate that the company knows it is a business imperative to make women feel safer on its platforms. Match Group brought in a new vice president to head trust and safety whose job partly focuses on complying with increased global transparency requirements. The company is experimenting with requiring faces in photos and rolled out a “Share My Date” feature so you can be tracked while meeting up with an online stranger. On Tinder, it orchestrated a “major ecosystem cleanup” geared toward identifying fake profiles and getting scammers off the app.

But neither the cleanup nor tracking a date from your phone would have stopped Matthews — a man who never sought to hide his identity, who assaulted his dates in his own home — from finding and harming women.

Four years after Matthews’ first documented assault, he walked into a wood-paneled courtroom in Denver and was sentenced to 158 years to life in prison. “I will sentence. I cannot heal,” Judge Eric Johnson told the room filled with survivors and family members.

“Countless women have suffered and will continue to suffer,” said Laura Wolf, an attorney who represented the woman whose police report triggered Matthews’ arrest. “Hinge and other dating platforms have taken no steps to ensure the safety of the product they are selling, matching unsuspecting women to known predators without pause or concern.”

Match Group didn’t make it easy for the Denver prosecutors to convict Matthews. A search warrant was issued to Hinge in July 2023. Two months later, prosecutors were still empty-handed — with the judge in the case asking at a hearing if he needed to start “dragging people in to get stuff done.” It wasn’t until February 2024 that the Denver District Attorney’s Office said they finally received documents returned by Match Group.

Matthews will likely never leave prison. Match Group executives currently face no charges. But the company knew about Matthews, and it knows about thousands of other abusive users. It has the data that could help users avoid dangerous situations, but it hasn’t shared it, leaving millions of people in the dark.

Lawmakers around the world are starting to ask for answers from the most powerful force in modern dating. In June, Colorado passed a law, triggered by the Matthews case, that forces dating app companies to tell the state attorney general what safety measures they are taking to protect users. Although the law leaves room for the possibility of additional transparency in the future, it does not currently require the company to tell the state, or the public, how many people are raped or assaulted after using its platform. In the U.S., we’ve just scratched the surface. In most states, there’s little that requires Match Group to share information with you — or with Congress.

The reality is that if Stephen Matthews were released today, he could get right back on a dating app. Match Group knows this — and now so do you.

Stephanie Wolf contributed reporting. Statistical journalist Natasha Uzcátegui-Liggett led The Markup’s testing of Match Group apps.