Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Hello, hello,

This is my first time on the Markup mic, so I’ll introduce myself: I’m Michael Reilly, The Markup’s newly installed managing editor. I am not much of a heat person—I tend to melt when it’s really sweltering—but I do love summer. Pool parties, barbecues, long afternoons and balmy nights, and generally being outside: What’s not to love? Oh, and of course, books. Books are good all year round, but there is something special about finally getting that time to relax in your backyard on a warm afternoon or chill at the beach, letting time slow down for just a bit as you get engrossed in a book.

As you might expect, we at The Markup love a good read. Below you will find recommendations for works ranging from fast-paced fiction to deep interrogations of the history of technology. There’s even a graphic novel (which sounds absolutely fascinating). Whether you’re looking to expand your horizons or to be transported during some well-earned downtime, I hope you find something that strikes your fancy.

Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

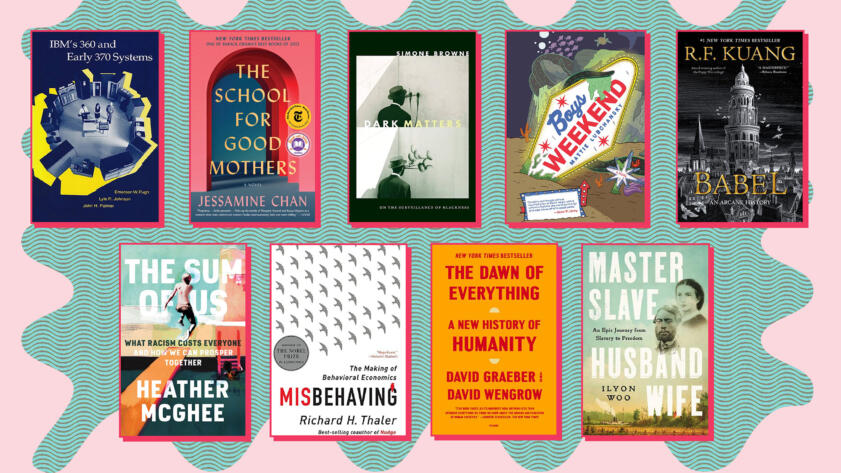

IBM’s 360 and Early 370 System

By Emerson W. Pugh, Lyle R. Johnson, and John H. Palmer

System/360 is the most important computer you’ve never heard of. This family of mainframes was announced by IBM nearly 60 years ago and ushered in a staggering range of innovative technology still in use today, from virtual machines to processor caches to semiconductor memory. It also provided the industry with dramatic lessons on how tech development could be mismanaged, including by failing to anticipate important consequences of innovation. “IBM’s 360 and Early 370 Systems” provides a masterly and fascinating account of the project and its impact across several decades, drawing on company records and more than 100 interviews.

Markup readers will be particularly struck by how the tech sector keeps forgetting old lessons: Just as today’s programmers must rewrite apps like Twitter for different online contexts, developers used to have to rewrite all their programs for each new model of computer, until System/360 introduced the idea of a software compatibility. And just as users today find their data locked up in different clouds, users in the 1960s struggled to move their files from one machine to another, at least until System/360 pioneered standard storage interfaces and removable disks. Allowing people to truly own their data and software may not be a new idea, but it remains as resonant as ever. — Ryan Tate

The School for Good Mothers

By Jessamine Chan

Jessamine Chan’s “The School for Good Mothers” imagines a world where the government uses technology to surveil parents and puts them into a Big Brother–like environment to help them become better caretakers. Through the eyes of protagonist Frida Liu, we experience what it’s like to have a governmental agency test and evaluate your moral character with technological means. In this system, Liu hems and haws about her ability to be a good mother and continues to belabor the moment that got her in the situation in the first place—a lapse of judgment during which she left her toddler alone in the house for two hours to have a coffee. The novel allows us to ask important questions: Are we the sum of our worst actions? Can we truly judge someone’s character through metrics and data points?

Science fiction is one of the most visceral ways for us to explore human truth: Take the present moment, observe the issues plaguing society at the time, imagine an exacerbated version of them in the near future. It’s a practice that authors like Octavia E. Butler perfected and that is truly coming out in Chan’s “The School for Good Mothers.” Her novel picks up on something I’ve been really trying to pinpoint in my reporting: What are the psychological pressures exerted on people who are suddenly watched and evaluated by a system that was engineered by humans but has no ethical oversight beyond its construction? We all feel it: the weird pressure we have on Instagram to look our best, the need to perform tasks faster when you know you’re being monitored, the ways in which the imagination of teachers is constrained when they are told their students’ test scores count toward their evaluations. “The School for Good Mothers” examines the inner turmoil these systems create with an emotional exactitude that hardly feels fictional, even if it’s set in a fictional world. — Lam Thuy Vo

Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness

By Simone Browne

As a reporter and data journalism professor, I often think about how statistics are collected and, perhaps more important, who gets to determine what kind of data is collected. We often believe that people who use scientific methods are exempt from racial bias—a belief that can be described as technochauvinism. But it’s hard to deny that many technological systems that govern our lives are deeply flawed. Who makes the decisions about what data is collected matters a lot. And often it shows in the kind of data that is produced—whether it’s crime data that shows bias against Black and Latino folks or whether it’s an algorithm coming up with scores that predict that Black students are less likely to graduate.

Simone Browne’s “Dark Matters” is an examination of those who observe and those who are observed. It is a dense read largely because it combines theoretical scholarship with important historical documents, but it also feels like one that is important to understanding our data-fied society. Blackness was often surveilled in ways that were oppressive. In one section, for example, Browne explains how “the first large-scale public record of black presence in North America” was the “Book of Negroes,” in which slave owners would describe enslaved Black people largely using their physical markers to “serve as a record in case of claims for compensation.” In another, she explains how lantern laws were introduced to monitor “Black, mixed-race, and indigenous people,” who were seen as security risks. Under those laws, enslaved people were required to carry a candle after dark, and if they failed to do so, they were subject to punishment of a public whipping of no more than 40 lashes.

In an era where data is used to build profiles of everyday people, this book serves as a good reminder that there is a potential for bias and sometimes even violence to be built into the gaze of those who observe. — L.T.V.

Boys Weekend

By Mattie Lubchansky

“Boys Weekend,” a new graphic novel from Mattie Lubchansky, takes the premise of a bachelor party in a techno-libertarian, seasteading bacchanal where everything is legal (even hunting your own clone for sport) and turns it into a slyly moving meditation on gender identity and capitalism. Lubchansky, an editor at comics magazine The Nib, which sadly just published its final issue, wrote and illustrated the tale of a transfemme artist suffering through a college friend’s bachelor party, simultaneously navigating being the “best man” who is not a man and also the Lovecraftian cult that is effortlessly brainwashing its way through a party island full of dull, misogynistic tech bros.

It’s a speedy read, packed to the brim with subtle visual gags, that builds to an action-packed climax. But the emotional core—a journey toward acceptance, both from the self and by friends from the past—lingers like a hangover. Not “The Hangover,” which is about how the debauched indulgences normative for bachelor parties can be destructive of participants’ personal lives, but a hangover from the realization that those debauched indulgences are merely extensions of a wider culture that can’t help but prioritize consumption over real human connection. — Aaron Sankin

Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution

By R.F. Kuang

Summer is the time for adventure stories, and what could be more adventurous than a story about … students at an early-19th-century translation institute at Oxford University? O.K., bear with me. “Babel” won the 2022 Nebula Award for best novel on the strength of its gripping plot, clever world-building, and thoughtful exploration of colonialism, assimilation, and academic complicity in the military industrial complex. In an alternate but familiar time line around the 1830s, the British Empire is at the peak of its power thanks to its colonial monopoly on silver inscribing. The magic that powers the Industrial Revolution in this universe relies on bilingual translators inscribing a match-pair of words in two or more languages on a bar of silver. Whatever meaning is lost in translation between those words will manifest magically, and Britain uses this magic to accrue ever more wealth and influence around the world in the name of free trade. Even when “free” means “at gunpoint.”

Amid these swirling mercantile and geopolitical forces, Robin Swift, a young Chinese orphan, is spirited away from Canton and raised to be translator at the rarified Royal Translation Institute at Oxford (aka Babel), where he is highly valued for his Chinese-language ability. He must reconcile his alienation from racist British society and the violent colonialism that his work supports with the relative privilege of his position and his love for the only place that has ever felt like home. As 50 percent magic-school fantasy, 50 percent spy thriller, and 100 percent thought-provoking, “Babel” is a great read on the beach, at the airport, or in a grand Oxford library. — Jesse Woo

The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together

By Heather McGhee

A fascinating look at the broader effects of systemic racism and how it steals prosperity from everyone. In a data-based analysis that essentially says, “This is why we can’t have nice things,” “The Sum of Us” does a deep dive into historical examples of White Americans losing out on opportunities due to the racist policies that were ostensibly for their benefit. From popular public swimming pools closing down completely rather than allowing racial integration to slavery starving Southern states of infrastructure investments that are still missing to this day, author Heather McGhee offers cautionary tales as a path toward a more inclusive and equitable society, emphasizing that true prosperity can only be achieved when we recognize that we all rise or fall together. — Ramsey Isler

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

By Richard H. Thaler

Behavioral economics is a fascinating field that sheds light on the often irrational choices humans make with their money, and this book, written by an author who would later win the Nobel Prize in economics, is the perfect way to jump into the topic. With plentiful examples, real-world case studies, and healthy criticism of the assumptions made in traditional economics, “Misbehaving” explains the human patterns that drive markets and will have you questioning the biases and misconceptions behind your own consumer habits. — R.I.

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity

By David Graeber and David Wengrow

History has a lot to teach us about why the modern world is the way it is. But as we know, history is often taught by someone with an agenda. That is certainly true in David Graeber’s and David Wengrow’s mind-blowing book, “The Dawn of Everything.” The agenda they’re pushing, though, is one I (and I suspect a lot of Markup readers) can get behind: They use hard evidence—mostly anthropological and archaeological—to understand how people lived before the rise of the capitalist mega-society we live in today, as well as to examine why we often tend to think our current state of affairs is the product of some kind of inexorable social evolution. (Spoiler: It’s not.)

I won’t lie, this book is a tome—but it takes a bit of work to convincingly refute centuries of received wisdom dating back to Europeans’ contact with the indigenous cultures of North America. One thing I will say is it doesn’t take long to get to the point: Before the tour de force of evidence even begins, Graeber and Wengrow skewer everyone from Steven Pinker to Jean Jacques Rousseau in ways that made my head explode and had me laughing out loud. (I may have a weird sense of humor, but seriously, even the footnotes are funny.)

The overall result is no less stunning. The authors show, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that humans are a fascinatingly creative, complex social species who have organized themselves in a wild array of different social structures over the millennia. It’s only recently that we’ve become stuck in a system of living that assigns outsized power to people who have amassed material wealth or who hold political office. And while we may be under the impression that it’s in our nature to be separated into classes of rulers and those being ruled, it absolutely does not need to be that way. In fact for the vast majority of history, it wasn’t. — Michael Reilly

Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom

By Ilyon Woo

“Nonfiction that reads like fiction” is how this book was first described to me, and it’s absolutely accurate. “Master Slave Husband Wife” tells the real story of a husband and wife who escaped slavery in the 1840s not by any kind of underground railroad but by booking passage on trains and steamboats. Ellen Craft disguised herself as a young White gentleman traveling up the coast to seek medical care, and her husband, William, pretended to be her slave.

The author weaves together so much detail about their journey and makes clear what she knows from historical context and what she knows was certainly a part of Ellen and William’s experience. It’s a gripping read, and one that makes clear the very real danger the two of them constantly faced, even after a successful first leg of their journey. — Sisi Wei

Thanks for reading, and happy reading,

Michael Reilly

Managing Editor

The Markup

Correction

This article has been updated to correct an error in the book title “The School for Good Mothers.”