Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Meredith Broussard is not your usual AI scholar. Sure, the data journalist and associate professor at New York University has written about the dangers of AI in the academic realm for years and has been a staunch critic of “technochauvinism,” a term she coined in her 2018 book, “Artificial Unintelligence,” for the seemingly blind belief that we can use technology to solve any problems.

But what’s also notable about Broussard’s work on AI is that she has found ways to convey just how much AI has already infiltrated the lives of everyday people. In her latest book, “More than a Glitch,” for instance, she writes about various tangible examples that bring to light the very significant and at times problematic ways AI is already affecting various facets of people’s lived experience, whether it be soap dispensers that do not recognize darker skin tones or the AI technology that told her she had cancer.

And this book is not just for Big Tech developers or professors who debate the ethical implications of AI. Her book is written for people of all tech-literacy levels. You can tell Broussard is a teacher as well as a scholar; she’s not afraid to explain some of the most obscure issues in plain words.

In light of the current frenzied and much (over)hyped discourse around AI, The Markup decided to talk to Broussard again and get her take on AI—how it currently factors into our lives and what the biggest misconceptions about the technology are.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lam Thuy Vo: You’ve written about AI for years, and now everyone is talking about it. Would you mind giving us an overview of what AI is?

Meredith Broussard: AI is just math. It’s very complicated, beautiful math. Another way of thinking about it: AI is statistics on steroids. In my new book, “More than a Glitch: Confronting Race, Gender, and Ability Bias in Tech,” I try to demystify AI and collect examples that show why we shouldn’t rush headlong into an AI-enabled future.

Vo: Do you have any examples of what it isn’t or how it’s commonly misunderstood?

AI is just math. It’s very complicated, beautiful math.

Broussard: People tend to get “real” AI confused with Hollywood AI. We all tend to think first about the Terminator, or any of the other fabulous AI representations that we have from Hollywood whenever we think about artificial intelligence.

And honestly, it’s really fun to imagine sci-fi technological futures. But when we’re talking about AI and its role in our lives nowadays, it’s really important to stay centered on what’s real about AI as opposed to what’s imaginary about AI.

Vo: You brought a very personal story to your book: how a technology using AI diagnosed you with cancer. Tell us a little bit about the moment you realized this and how it spurred you to action.

Broussard: In one of the chapters of the book, I took my own mammograms and ran them through an open-source AI to see if the AI would detect my breast cancer. I did that as a way of writing about the state of the art in AI-based cancer detection. I got interested in AI for cancer when I saw a note in my chart that said, “An AI read this scan.” I was curious: What did the AI find? Who wrote the AI? What kind of biases did it have? But then I got busy with (human-enabled) cancer treatment, and I forgot about the AI for a while. After I was better, I decided to do an experiment to see if an open-source AI would detect the cancer that was obvious to my doctor.

We tend to hear things like, “Radiologists are going to be replaced by AI in the next few years.” They are not. Maybe, possibly, someday—but not anytime soon. There was an article in The New York Times several months ago that seemed to indicate that breast cancer detection AI was right around the corner. In reality, AI for cancer detection has been available since the 1990s—and it hasn’t gotten good enough to replace doctors yet.

In reality, AI for cancer detection has been available since the 1990s—and it hasn’t gotten good enough to replace doctors yet.

The AI that I used did, in fact, work. But it doesn’t diagnose the way that a doctor does. It drew a circle around an “area of concern” on a single flat image and gave me a score between zero and one. It did not give me a sentence summary like, “Sorry, you probably have cancer,” or display a percent chance that the area of concern was malignant; it just made a circle and a score. I realized that I had expected more—not the Terminator, and not a Jetsons-style robot doctor, but at least a humanlike diagnosis based on my entire medical record. This is pretty typical. We often have imaginary expectations about AI, and the technology fails to live up to what we imagine it can do.

It would be really great if we could diagnose more people earlier. It would be great if we could use technology to save more lives from cancer. We are absolutely all united in that goal. But the idea that AI is going to be our salvation for diagnosing all cancers in the next few years is a little bit overblown.

Vo: You coined the term “technochauvinism,” and you’re hinting at its definition in your answer. Can you tell me a bit more about that?

Broussard: Technochauvinism is a kind of bias that says that technology or technological solutions are superior. You see a lot of technochauvinism in the current rhetoric around artificial intelligence. People say things like, “This new wave of AI is going to be transformative, and everything’s going to be different.”

And honestly, people have been saying that for the entirety of the internet revolution, which we’re more than 30 years into now. The internet is not young and hip and new. The internet is middle-aged. We can make more balanced decisions about it now. And we need to pay attention to the rhetoric that people are using about technology, because each new technology trend is not going to change everything fundamentally.

Technochauvinism is a kind of bias that says that technology or technological solutions are superior.

Vo: That’s a great segue. Let’s talk about ChatGPT and other large language models for a second. Since the technology has been unleashed to the general public, many people have spoken about the harms of this technology, including 350 leaders in tech and AI who signed a one-sentence letter worrying about the potential of AI to bring about human extinction. What do you make of this hype around AI and the kind of conversation it produces?

Broussard: I think it’s important to center our conversations on the real harms that are being experienced by real people every day at the hands of AI.

There are cases like the recent Suspicion Machines story from Wired and Lighthouse Reports about an algorithm in Rotterdam that was allegedly trying to detect welfare fraud. All the algorithm did was identify recent immigrants. Those are the folks who probably need public assistance pretty badly. The algorithm was saying, “No, we’re going to restrict your access to public benefits.”

We have things like recidivism algorithms that are racially biased. Or even things as simple as soap dispensers that don’t read darker skin. Or the fact that smartwatches and other health sensors don’t work as well for darker skin. Things like selfie sticks that are supposed to track your image? Those also don’t work that well for people with darker skin because image recognition in general is biased.

So there’s lots of bias built into all of these AI systems. It’s technochauvinism to claim that these systems are superior. And overall, I think that we need to pay more attention to the biases of the real world that are baked into these systems. We need to stop assuming that AI or any kind of technology is going to be salvation.

It’s important to center our conversations on the real harms that are being experienced by real people every day at the hands of AI.

Vo: There’s been a lot of “doomerism” talk around AI that renders many of us powerless. What are real things that could be implemented right now to stop the harm that AI is already doing?

Broussard: I think that overall we need more computational literacy. One of the things that I try to do in my book, and in my work in general, is explain complex technical topics in plain language in order to empower people to speak up when algorithmic decisions are unfair or unjust.

Many people who make technology like to portray it as mysterious and powerful. This is a way of gatekeeping and a strategy for convincing people to spend more money on technology. When you feel disempowered, and when you feel like there’s a force making a decision and you don’t have a voice in it, then you don’t feel empowered to speak up.

But algorithms and computers are not necessarily any smarter than human beings. The computers are going to make a lot of really bad decisions. So people should feel empowered to speak up.

Vo: You talked to me about the “endpoint” of knowledge in AI. Tell me about how that applies to ChatGPT and other large language models.

Broussard: One of the things that many people don’t realize about large language models (LLMs) is that they are frozen in time. We think about AI as being so flexible, and we talk about AI learning from interactions, but actually an AI’s ability to “learn” is more limited than a human’s. When you make a machine learning system (like an LLM), you take a whole bunch of data (often this “training data” is scraped from the internet), you feed it into the computer and instruct the computer to make a model. The model shows the mathematical patterns in the data. Then, you can use that model to generate new language or generate new images or make decisions or make predictions. That’s how every large language model works.

You have to decide on an endpoint for your training data. The current free iteration of ChatGPT, to the best of my knowledge, ends in September 2021. We’re always adding new stuff to the internet, every moment of every day, but you can’t add all the up-to-the-minute stuff on the internet because it takes time and a lot of energy to train an AI model. So you have to decide, O.K., what is the point up to which I am going to include information? So, September 2021 is the end of what that large language model knows. [Editor’s Note: ChatGPT recently announced that a paid version will have access to up-to-date information from the Microsoft search engine Bing, a feature that will eventually be added to the free version.]

There’s something really static about thinking about freezing knowledge as of 2021. If we’re talking about something like how to build a birdhouse, that hasn’t changed very much. But social attitudes around race, gender, and disability have changed in the past two years. And if you are depending on knowledge that is old, then you’re not going to achieve social progress. It’s not a very flexible situation.

Think about whose voices are represented on the internet and think about who’s been bullied off the internet.

I’m also concerned for the future of history because there’s an awful lot of knowledge that’s not being posted openly or preserved on the internet. If you start believing that large language models encapsulate the entire internet—which they do not—then you have a very, very narrow view of what knowledge counts in the world. It’s just not a very expansive, inclusive view.

Think about whose voices are represented on the internet and think about who’s been bullied off the internet. If you think about the dominant voices in digital spaces, those voices are rarely women or people of color. So it’s easy to predict what kind of voice will come out of large language models.

This is not to say that large language models are not nifty. They are really nifty, and they are fun to use for the first 20 minutes. LLMs are an impressive scientific achievement. I think that everybody should learn about them, should use them, and should not be scared of them. I’m willing to believe that LLMs are useful for something. What that is, I don’t know yet.

I also think that people should read the stochastic parrots paper and understand the potential dangers of larger language models.

Vo: Now that AI is a bigger part of the general discourse, what is one thing you’d want everyday consumers of technology to take away from this conversation?

Broussard: I think it’s important to manage our expectations around technology. People expect it to feel special when they use AI. You hear a lot of hype, and you finally interact with a conversational AI or an AI app, and you kind of expect that it’s going to be exciting. You think it’s going to be different and transformative because you are Using Artificial Intelligence. But actually, you’ve been using AI for years without recognizing it.

There is AI in search engines. There are upward of 250 different machine learning models that get activated every time you do a simple Google search. Whenever you record a Zoom conversation and transcribe it automatically, guess what? You’re using AI. If you ever used any of those filters on Snapchat to put cat ears on yourself, that’s AI. It wasn’t labeled as AI because the marketers didn’t think that it would enhance the experience until recently, when AI got really sexy, and now everything is AI.

Actually, once you use it, AI feels mundane. It just feels like using any other technology. So we really need to reckon with our own expectations, turn down the hype, and close the gap between what we imagine and what the reality is.

Thanks for reading,

Lam Thuy Vo

Reporter

The Markup

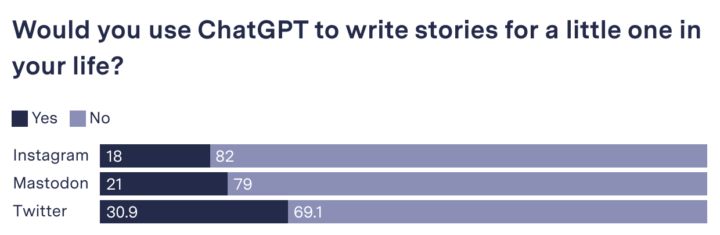

P.S. Last week, we asked on social media whether you’d use ChatGPT to write stories for a little one in your life. Of the 438 respondents, most readers said no. Take a look at the results: