Last year, Facebook quietly moved to prevent advertisers from choosing the race of the people who would see their ads. The move—which eliminated ad targeting categories like “African-American multicultural affinity”—came after years of criticism of the company for failing to prevent such categories from being misused to discriminate against people. Federal law prohibits racial discrimination in employment, housing, and credit opportunities, and time after time, researchers and journalists had found ads in those categories on the platform clearly targeted at Facebook users of certain races.

The Breakdown

Does Facebook Still Sell Discriminatory Ads?

We found discriminatory ads can still appear, despite Facebook's efforts

In response, Facebook—which has long argued that advertisers, rather than the company, are responsible for properly complying with civil rights laws—has largely taken a piecemeal approach. When a reporting team at ProPublica (led by now Markup editor-in-chief Julia Angwin), as part of a 2016 investigation into discrimination, was able to buy housing ads that excluded people of certain “ethnic affinity” categories on Facebook, the platform eliminated the “ethnic affinity” categories” for certain types of ads. And then last year, when The Markup found a job ad targeted to people of “African-American multicultural affinity,” Facebook killed the “multicultural affinity” category.

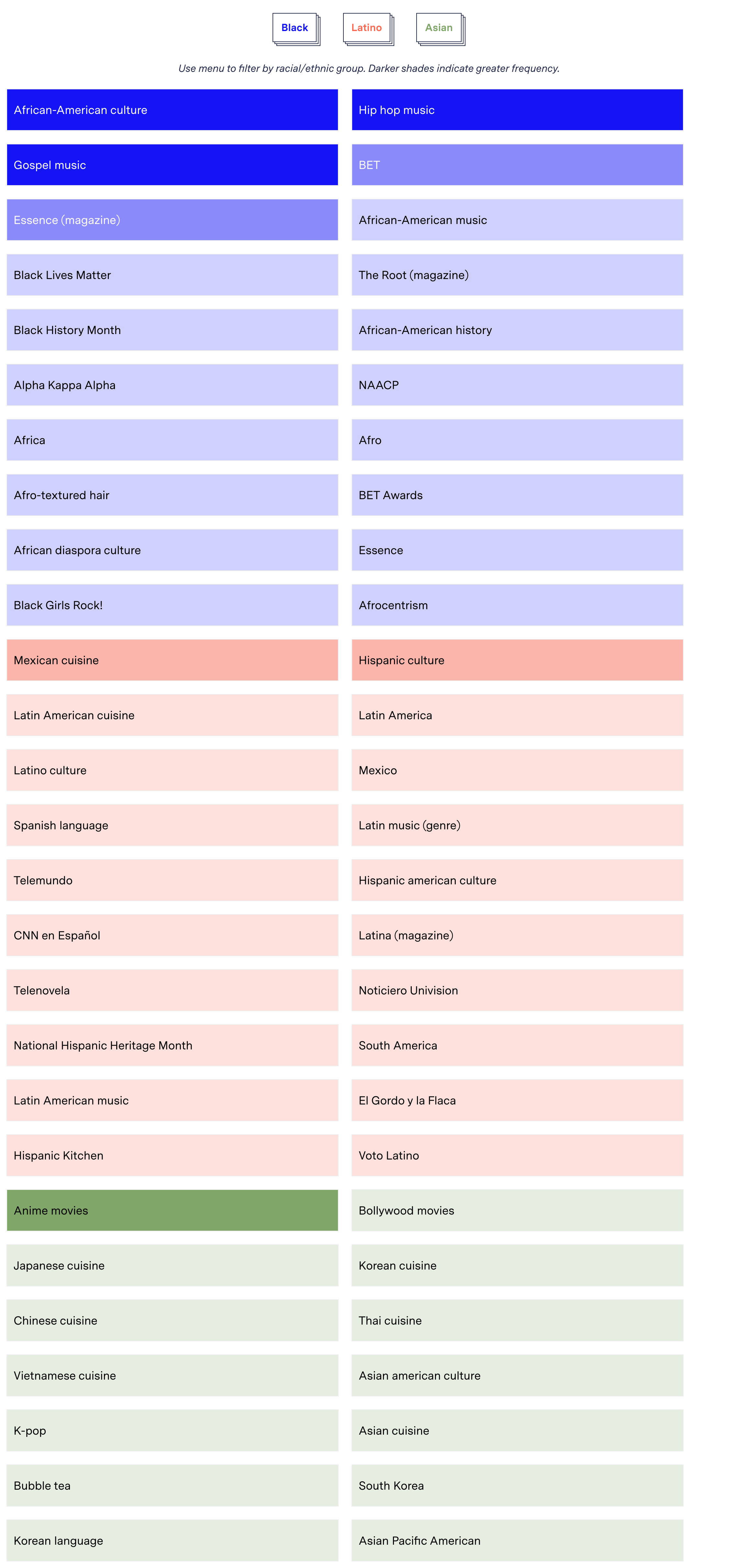

But while advertisers can’t explicitly target “Black,” “Latino,” or “Asian” Facebook users with their ads, The Markup has found a wide array of proxies for racial categories being used by advertisers on the platform through our Citizen Browser project. Citizen Browser consists of a paid nationwide panel of Facebook users who automatically share their news feed data with us, including which ads they’re shown. Using Citizen Browser data from March 16 through July 8, we searched our users’ news feeds for ads that were targeted to people interested in “African-American culture,” “Asian Culture,” and “Latino culture”—all categories Facebook provided as choices to advertisers. Searching for those racial proxies in our data yielded a whole slew of other ad categories that advertisers had used to zero in on the races of users they wanted to reach with their ads. This search did not find any ads that appeared to violate civil rights laws.

Examples of Proxies for Race in Facebook Advertising

Ads found in Citizen Browser panel news feeds

We found ads run by Family Dollar, Hennessy, the California Department of Health, and others that appeared to specifically target Black Facebook users with combinations of interests including “African-American culture,” “BET Awards,” “Black History Month,” “Historically black colleges and universities,” “Black Girls Rock!,” “Gospel music,” and “Afrocentrism.”

An ad for a new Jennifer Hudson film about Aretha Franklin targeted users with interests in “Movies” and “African-American culture.” One Family Dollar ad we found targeted users with interests in “Coupons” and “Discount stores,” but also “National Association for the Advancement of Colored People,” “Black History month,” “Afrocentrism,” “Black Girls Rock!” and several Black fraternities and sororities.

Facebook did not respond to requests for comment.

MyPillow, Hormel Chili, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services all ran ads targeting users with an interest in “African-American culture.”

Hennessy, the California Department of Health and Human Services, Hormel Foods, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The MyPillow ad, which was observed on one of our panelists’ timelines from April 18 through April 22, had been liked 3,700 times. In an emailed response to a request for comment, MyPillow’s media inquiry account replied “We don’t have any ads like that so you’re lying.”

Kayleigh M. Painter, a spokesperson for Dollar Tree, Inc. (which owns Family Dollar), said the company’s advertising is “multifaceted” and aims to target the diverse community that its stores serve. “We do not focus our marketing efforts on just one cultural community,” Painter said.

Till Speicher, a Ph.D. candidate at The Max Planck Institute for Software Systems, who has researched discrimination in ad targeting, says providing racial proxy categories to advertisers leaves room for discrimination.

The approach that Facebook seems to be pushing is not really sufficient to prevent discrimination…. If you’re determined, you can find some way around that.

Till Speicher, The Max Planck Institute for Software Systems

“The approach that Facebook seems to be pushing is not really sufficient to prevent discrimination, because there are basically so many different methods of targeting that it’s really hard to regulate them all to prevent discrimination,” he said. “If you’re determined, you can find some way around that.”

Facebook doesn’t specify exactly how it determines what its users’ interests are, but the company does say that a user’s activity both on and off Facebook sends data to the platform that is used to infer interests. Any user can view a list of the interests Facebook keeps on them in the Ad Preferences section of your Facebook settings (Settings & Privacy > Settings > Ads > Ad Settings > Categories used to reach you > Interest Categories). Users can remove interests but not correct them or add new ones.

Facebook does provide an Ad Library that includes some information about currently running ads, but the tool lacks ad targeting information. Aaron Rieke, the managing director at Upturn, a group that researches Facebooks’ impact on society (The Markup’s president, Nabiha Syed, and board member Paul Ohm both sit on Upturn’s Board of Directors), said Facebook should release much more data than it does on its advertisements and how they’re targeted. “What that would allow researchers to do is to take a much deeper look at how these close racial proxy categories are actually being used on the ground.”

Additional reporting by Corin Faife.