Facebook is blaming “technical issues” for its broken promise to Congress to stop recommending political groups to its users. Facebook made the pledge once in October, in the run-up to the presidential election, and then falsely reiterated it had taken the step after rioters overtook the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, a deadly event partially coordinated by users on the platform.

The Markup first revealed that Facebook was still recommending groups like “Donald Trump Is Our President” and the “Kayleigh McEnany Fan Club” in an investigation published on Jan. 19. Examining the top 100 groups recommended to roughly 1,900 users on our Citizen Browser panel, we identified 12 as political—including groups with posts calling for violence against lawmakers, spreading election-related conspiracy theories, and coordinating logistics for attending the rally that led to the Capitol riot.

Show Your WorkCitizen Browser

How We Built a Facebook Inspector

The Citizen Browser project seeks to illuminate the content Facebook elevates in its users’ feeds

Citizen Browser is a data-driven project examining the choices Facebook makes about what content to amplify.

A week after our report, U.S. senator Ed Markey sent a letter to the company, demanding an explanation, and on Feb. 10, Facebook replied in a letter to Markey:

“The issue stemmed from technical issues in the designation and filtering process that allowed some Groups to remain in the recommendation pool when they should not have been,” Facebook said in its response. “Since becoming aware of this issue, we have worked quickly to update our processes, and we continue this work to improve our designation and filtering processes to make them as accurate and effective as possible.”

To determine whether or not a group recommended to our panelists was political, The Markup examined the group’s name, it’s “about” page, its rules, and when possible, posts in the group’s discussion feed.

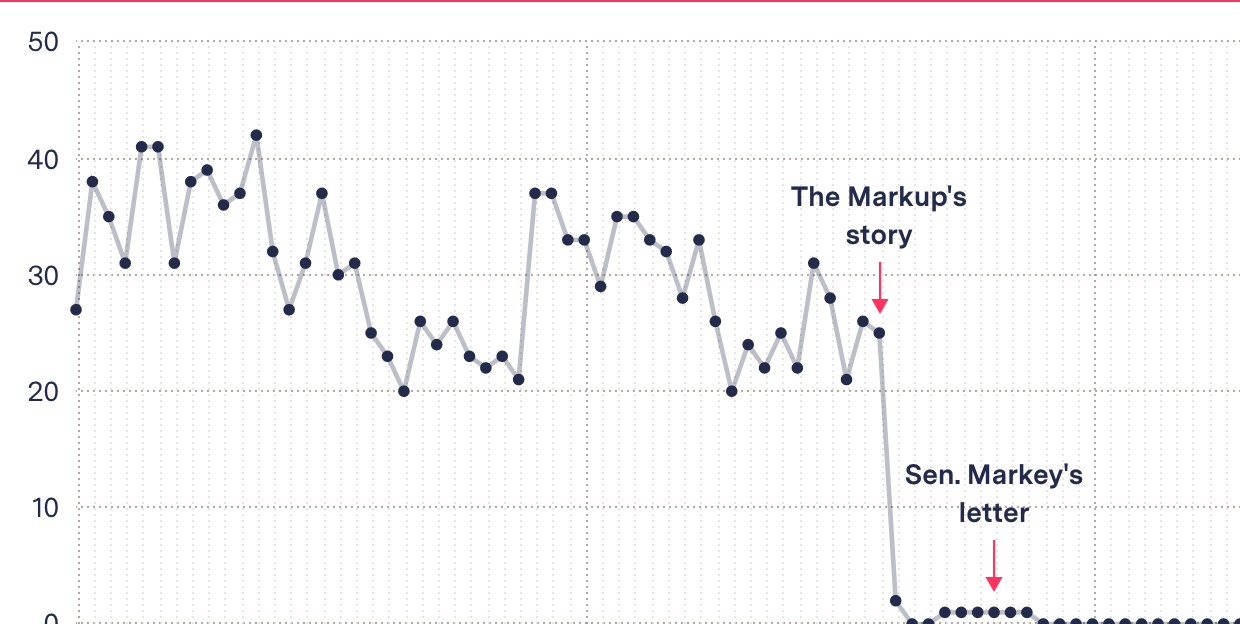

Following publication of our story, recommendations for political groups dropped precipitously, as our Citizen Browser panelist data shows.

In the days following our initial report, Facebook’s recommendations for political groups plummeted

Political groups recommended to Citizen Browser panelists

0

10

20

30

40

50

December

January

February

While recommendations for some political groups lingered, they virtually stopped on Jan. 29, three days after Facebook received Markey’s letter. The political groups recommended between Jan. 20 and Jan. 28 were presidential fan clubs for Biden and Harris, or Trump.

“A policy is only as good as its enforcement. I commend Facebook for finally heeding my calls and committing to stop recommending political groups, many of which have become some of the most toxic corners of the internet,” Markey said in a statement. “Now, it’s time for Facebook to start making good on that promise, and I will be closely monitoring this issue moving forward.”

Facebook said in the letter that its method for pausing political group recommendations was to designate certain groups as “civic” and set up filters to remove tagged groups from being recommended.

“While there were occasions when our system mistakenly recommended civic groups, these instances were infrequent and the issue has been addressed,” said Andy Stone, policy communications director for Facebook. Stone said the company looks at a variety of things, like the title and description of a group, as well as its content, to determine if a group is civic.

The attempt to algorithmically remove politics from platforms seems, to put it bluntly, doomed to fail.

Deen Freelon, UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media

“The attempt to algorithmically remove politics from platforms seems, to put it bluntly, doomed to fail,” said Deen Freelon, associate professor at the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media.

The “technical issues” meant that, from Election Day on Nov. 3 to the Jan. 6 Capitol Hill riots to President Biden’s inauguration on Jan. 20, Facebook was still recommending political groups to its users.

Our analysis found that Facebook particularly pushed political groups to more conservative users. Twenty-five of the top 100 groups recommended to Facebook users in our panel who voted for Donald Trump were political. Meanwhile, for Biden voters, 15 of the top 100 groups were political.

Facebook’s own internal research has consistently pointed to the danger posed by political groups on its platform. Researchers warned Facebook in a 2016 internal report that 64 percent of new members of extremist groups joined because of the social network’s recommendations, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Citizen Browser

Facebook Said It Would Stop Pushing Users to Join Partisan Political Groups. It Didn’t

According to Citizen Browser data, the platform especially peppered Trump voters with political group recommendations

Even though Facebook’s recommendations have appeared to stop, the groups continued to grow during the social network’s lapse.

The “Kayleigh McEnany Fan Club,” a group that Facebook’s researchers identified as a distribution system for “low-quality, highly divisive, likely misinformative news content,” was still being recommended to one in five Trump voters in our Citizen Browser panel throughout December and up until Jan. 20.

Facebook’s internal researchers warned that “the comments in the Group included death threats against Black Lives Matter activists and members of Congress,” and Facebook had flagged it 174 times for misinformation within three months, according to The Wall Street Journal.

In December, the group had 432,000 members, but as Facebook continued to recommend the group, it grew to 443,000 members, on Jan. 19. While it was still being recommended, the Kayleigh McEnany Fan Club group gained a net average of 440 new members a day. After Facebook discontinued recommending the group, following our report, the group continued to grow, but at a rate that was 30 percent slower, adding about 300 new members a day between Jan. 19 and Feb. 10.

We found that among the 16 political groups that were recommended both before and on Jan. 19, daily membership growth rates shrank significantly from Jan. 19 to Feb. 10. Groups like “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Fan Club” and “Dan Bongino Fans” had membership growth rates drop by 40 and 93 percent, respectively. (See this data on GitHub.)

Subscribe to the Citizen Browser Newsletter

We’re investigating what content social media platforms amplify. Sign up for updates on what we uncover.

Removing civic group recommendations was the beginning of what’s become a larger effort to remove politics from Facebook. On Feb. 10, Facebook announced that it was testing tools to reduce political content on news feeds.

But activists worry about blanketly exorcising politics from the platform, saying grassroots groups that use platforms like Facebook to organize may get hit the hardest—groups that don’t have a budget for ads or even to build their own website.

“Facebook’s entire surveillance capitalist business model is fundamentally incompatible with democracy and basic human rights,” Evan Greer, deputy director for Fight for the Future, said. “Algorithmically suppressing groups that they deem to be ‘political’ won’t fix that, it will just undermine activist social movements, and disproportionately silence marginalized people.”

Greer also expressed concern that enforcement might fall unevenly across the political spectrum.

“Are they going to consider LGBTQ support groups ‘political’? If so will they also consider church groups political? The way they draw this line will have enormous impacts on people’s ability to be heard, and I don’t trust them to do it well,” she said.

In the period The Markup analyzed for our earlier story, December 2020, our 1,900 panelists were much more likely to be recommended conservative groups than liberal ones. Our analysis has limitations—our panel is tiny compared to the overall number of Facebook users and skews demographically older, whiter, and more liberal than the general population—but it provides rare insight into Facebook’s algorithms. And we encountered some disparities in the types of groups that Facebook appeared to boost over others.

Throughout December, 7 percent of our panelists received suggestions to join the “Kaleigh McEnany Fan Club.” Meanwhile less than one half of one percent were suggested any group with “Black Lives Matter” in its name.