Tech giants have won over two more states in their ongoing battle with worker advocates over the classification of gig workers. Georgia and Alabama are the latest states to pass laws ensuring that gig workers for companies like Uber, Lyft, Instacart, and DoorDash are not considered employees. The laws come on the heels of legislation passed in March in Washington State—which classified ride-hail drivers as independent contractors rather than employees. Delivery drivers for apps like DoorDash are not covered by the Washington law.

Last month, Florida passed a related law that protects companies from being sued for misclassifying employees as independent contractors if the company provides support during an emergency.

The Breakdown

Can Uber and Lyft’s Copycat Ballot Measure Win in Massachusetts?

After success in California, gig economy companies are looking to pass their own labor laws in the Bay State. But they may be in for a battle

In a win for labor groups, however, the Massachusetts Supreme Court on June 14 scuttled a ballot measure that would have classified gig workers as independent contractors.

The companies, which have built their business models on using independent contractors, have spent millions of dollars on lobbying and advertising campaigns. They have much at stake in keeping their workers from being classified as employees. For example, in its most recent SEC filing, Uber said it has paid approximately $372 million settling classification claims.

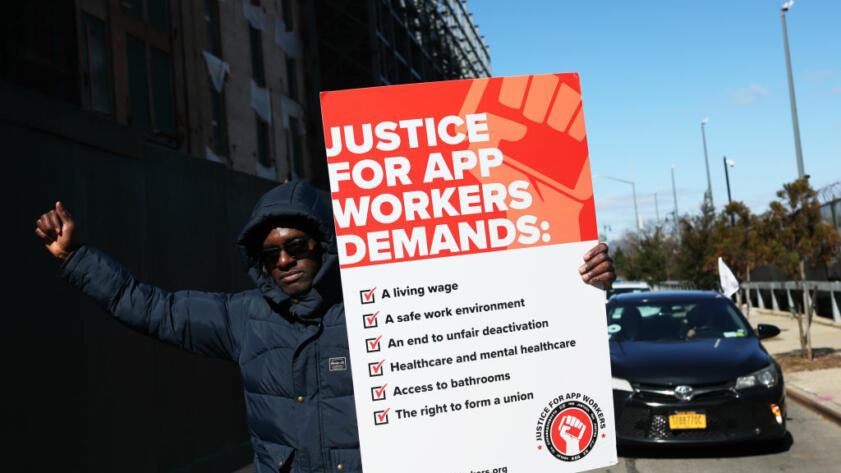

Worker advocates, on the other hand, say that the independent contractor classification gives ride-hail drivers and couriers second-class status, where they have fewer rights and fewer protections.

In the absence of federal legislation, gig companies have increasingly focused on changing state laws, said Veena Dubal, a law professor at UC Hastings.

When gig companies face the threat of having states interpret their workers as employees, “you see these kinds of laws,” said Dubal. “They find a place where workers have no political power, and no one’s paying attention.”

Under the Georgia and Alabama laws, gig companies must adhere to certain rules for their workers to be considered independent contractors, including not setting specific hours and allowing workers to use competing apps.

While the Washington law gives ride-hail drivers benefits, such as sick leave and a minimum wage when they have a passenger in their car, the Southern state laws have no such requirements.

“We are focused on finding solutions across the country that protect and strengthen independent work,” DoorDash spokesperson Eli Scheinholtz said in an email. “We are proud to stand for policies that preserve the independence, accessibility, and choice Dashers overwhelmingly value, as well as create frameworks that allow Dashers to access portable, proportional, and flexible benefits.”

Scheinholtz did not respond to a follow-up question about whether Doordash had plans to back any flexible benefit legislation in Georgia and Alabama.

Uber, Lyft, and Instacart did not respond to a request for comment.

The Washington law came after years of negotiations between Uber, Lyft, and Teamsters Local 117, which runs a worker group in the state called the Drivers Union. Teamsters Local 117 eventually backed a deal that resembles what the CEO of Uber has called the “third way,” in which drivers remain independent contractors but are given certain benefits.

The local’s parent union, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, however, did not support the law. When the bill passed, General President Sean O’Brien told Bloomberg, “This will be the model that sets the tone for the entire country.”

“App-based drivers are misclassified workers. Period. It makes no difference if it’s happening in Washington state or Massachusetts or any other state—gig companies are pushing an agenda designed to rob workers,” O’Brien said in an emailed statement to The Markup when asked about the Alabama and Georgia laws. “We need to take strong action at federal and local levels to put a stop to the intentional misclassification of employees.”

Georgia

The Georgia law, which goes into effect in July, gives the state’s Department of Labor the power to impose civil penalties on companies that misclassify workers.

It also includes a section that defines ride-hail and delivery workers as independent contractors—so long as the companies they work for adhere to certain conditions, including allowing workers to reject certain rides or deliveries, not requiring specific hours of work, and not barring the use of additional apps.

It’s this appearance of autonomy. We weren’t able to set our own rates. We were controlled by an algorithm.

Cherri Murphy, Gig Workers Rising

Cherri Murphy, a former Lyft driver and an organizer with worker advocacy group Gig Workers Rising, pointed out that even if gig companies don’t require specific hours, if drivers want to make money, they have to work when demand is high. That can be driving late at night when people are out partying.

“It’s this appearance of autonomy,” she said. “We weren’t able to set our own rates. We were controlled by an algorithm.”

The language cementing gig workers’ status as independent contractors was added to the bill as it worked its way through the Georgia legislature. Rep. Todd Jones, one of the bill’s sponsors, said gig companies have become key economic drivers in the state, and he thought they needed guardrails for treating their workers.

“I know gig workers who are on Uber, Lyft, Shipt, I mean, my god, they work maybe six apps at a time,” said Jones. “I didn’t want it suddenly where Grubhub says, ‘You can’t work for UberEats.’ ”

Alabama

Alabama passed its gig worker classification bill at the end of March. The law defines a company whose app allows workers to accept jobs from the public, like DoorDash or Uber, as a “marketplace platform.”

Workers will be considered independent contractors so long as the gig companies follow guidelines that include not setting specific hours and allowing drivers to reject some rides or deliveries, similar to the requirements under the Georgia law.

The Alabama law, which goes into effect in August, requires gig workers to agree in writing that they are independent contractors and that they will take on all work-related expenses. The law stipulates that platforms don’t provide work-related equipment.

Florida

The Florida law, which goes into effect in July, clarifies that businesses may provide workers with, among other things, PPE, health and safety training, and cleaning supplies without those actions being used against them in misclassification suits. It also states that a business can provide financial assistance to workers who are no longer able to work because of health and safety concerns without threat of such lawsuits.

Ballot Measure in Massachusetts

The Massachusetts ballot measure was backed by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart. In tossing the measure, the court found it didn’t hold up against a state law requiring all parts of a ballot question to be related and specifically took issue with vague language that would limit the companies’ liability for accidents by their drivers.

News

Uber and Lyft Donated to Community Groups Who Then Pushed the Companies’ Agenda

The ride-hail giants are orchestrating a complex PR scheme to sway public opinion to ensure drivers aren’t classified as employees

Flexibility and Benefits for Massachusetts Drivers, a committee that introduced the measure—and whose $17.8 million war chest was funded exclusively by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart—said it was dismayed by the decision.

“The future of these services and the drivers who earn on them is now in jeopardy,” Conor Yunits, a spokesperson for the committee, said in a statement.

Members of Massachusetts Is Not for Sale, a coalition of workers, consumers, and civil rights groups that opposed the ballot measure, applauded the ruling: “We are excited to continue the work of our coalition to ensure that drivers, riders, and taxpayers are protected from the greed of Big Tech CEOs,” said Wes McEnany, the campaign director of the group. “We will remain vigilant and united against any further attempts by Big Tech to water down worker and consumer protections in Massachusetts or beyond.”