While much of the country is engrossed in the presidential election, several big tech firms have their focus elsewhere: a slate of voter propositions on the California ballot, and in particular, one that would keep large swaths of app-based gig workers from receiving full employee benefits.

Proposition 22, if passed on Nov. 3, would exempt companies like Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart from certain provisions of California labor law and allow them to continue treating their drivers as contractors rather than employees. It would also confer certain benefits, like minimum pay rates and mileage reimbursements.

Collectively, those four companies have poured nearly $200 million into the campaign to pass Proposition 22, making it the most expensive ballot initiative in California history. (Opponents, meanwhile, have raised about $16 million.) But with app companies potentially reworking their business models, they’ve also turned to some unconventional tactics, including enlisting the very drivers at the center of the referendum into campaigning on the proposition’s behalf.

And the stakes have only gotten higher since California’s First District Court of Appeal ordered Uber and Lyft to start complying with a California labor law, AB5, requiring them to treat drivers as employees, within 30 days of the end of the appeal process.

Here’s a roundup of some of the more unconventional campaign methods tech companies are using to push for the prop’s passage.

Companies Are Enlisting Their Gig Workers and Employees to Help Campaign

According to a lawsuit filed last week in San Francisco Superior Court, Uber allegedly incentivized and coerced its drivers into publicly endorsing Prop 22.

“Uber has not only directed its drivers to vote for Proposition 22, but has also asked them to support the Yes on Prop 22 campaign by submitting video messages and statements that conform to Uber’s political position and by pressuring the drivers to submit statements of support for Proposition 22 and to respond to surveys regarding their voting preferences by stating they support Prop 22,” the lawsuit alleged.

The lawsuit also alleged that Uber encouraged drivers to make videos about their support for Proposition 22, with each driver “reasonably aware that Uber will know whether or not that driver has submitted a video and what the content of that video may be, and that Uber has the power to punish any employee who does not submit a supporting video.”

The BreakdownCoronavirus

How Are Gig Workers Faring During the COVID-19 Crisis?

Workers fight for hazard pay, protective equipment, and better sick leave

Uber spokesperson Davis White said the lawsuit was meritless and filed solely for press attention.

“It can’t distract from the truth: that the vast majority of drivers support Prop 22, and have for months, because they know it will improve their lives and protect the way they prefer to work,” White told The Markup.

San Francisco Superior Court judge Richard B. Ulmer Jr. denied a temporary restraining order against Uber on Wednesday, saying there was no evidence any driver faced retaliation for not going along with the campaign. The suit remains ongoing.

Uber did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the status of the suit or their solicitation of or retaliation against drivers.

It is a violation of California labor code to coerce, control, or incentivize employees to hold a certain political position—but that law doesn’t define where, exactly, the line is between encouraging versus coercing workers, and there is no law extending those protections to contractors.

“I don’t think that there’s any provision of California law that prohibits a hiring entity from declining to do business with a contractor who disagrees with their political positions,” said Beth Ross, an employment attorney. “I think that that’s what is part of what makes Prop 22 so very fraught and dangerous.”

Other companies are also enlisting their drivers in supporting Prop 22.

Eater San Francisco reported that DoorDash passed out “Yes on 22” bags to restaurants around California to use for takeout orders. DoorDash’s global head of public affairs, Taylor Bennett, referred all comments to the Yes on 22 campaign, whose spokesperson, Geoff Vetter, said Yes on 22 could not respond to any specific company activity. “Each company is communicating with their customers in various ways because of the high stakes in this election,” Vetter told Eater SF.

CNN Business reported that Instacart drivers in the Bay Area were encouraged to slip “Yes on 22” stickers into their delivery bags. Instacart did not respond to a request for comment for this story but told CNN Business that placing the materials in the bags was optional for the workers in a Bay Area store’s staging area.

KQED reported Uber drivers being subject to annoying pop-ups while driving around the Bay Area, pop-ups that went away when they signaled their support for Prop 22.

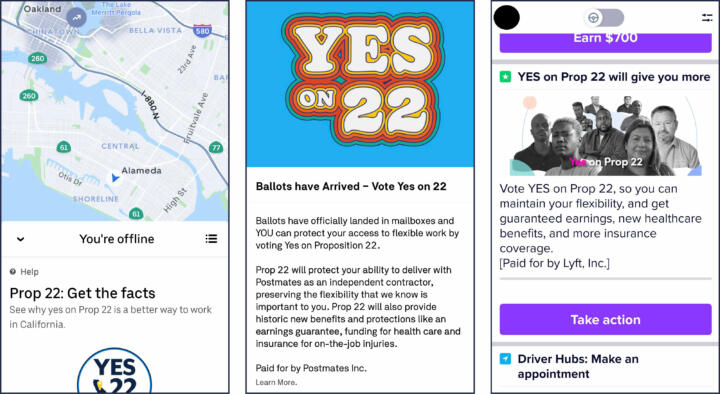

Drivers for Uber, Lyft, and Postmates sent screenshots to The Markup of pro–Prop 22 messages sent to them while they were on the job. The drivers did so on the condition that they remain anonymous, for fear of losing their work with the companies.

The Uber driver app also has in-app messages outlining the benefits promised by Prop 22, such as 120 percent of the minimum wage, at least $300 a month toward health insurance, and occupational medical insurance.

Matt Abt, a Los Angeles–based Postmates driver, said that Yes on 22 messages in that app were in the “newsroom” section and thus easily ignorable.

Lyft has a similar message in the “newsroom” section of its app, according to a San Francisco driver who wished to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation. Neither Postmates nor Lyft responded to requests for comment for this story.

Kurt Nelson, a software engineer for Uber and a former Lyft driver who opposes Prop 22, told The Markup that Uber has also been sending emails to office-based employees encouraging them to vote yes on Prop 22, including from Uber chief legal officer Tony West. The emails, according to Nelson, offered employees pro–Prop 22 materials such as signs, decals, and free T-shirts.

Uber declined to comment on the emails. Ross, the employment attorney, said the office emails were likely legal.

“This is a democracy, and I don’t think the California statutes would prohibit the transmission of information,” she said.

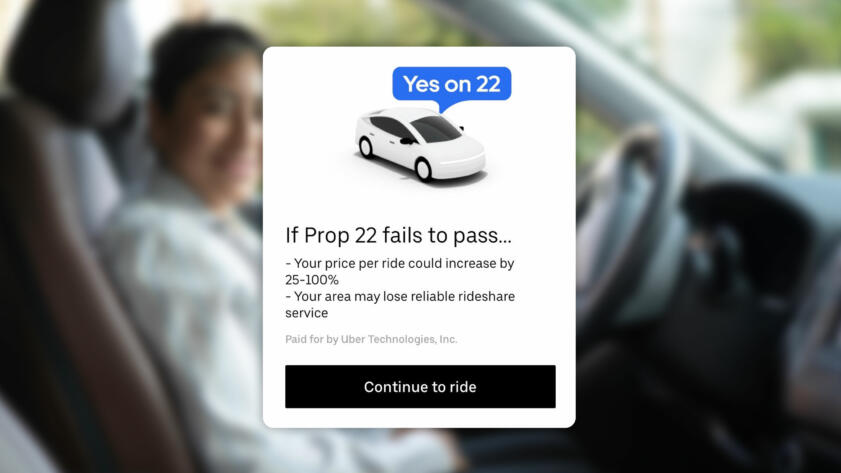

Companies Are Also Using Their Apps to Spam Customers

California app users have also received texts, emails, in-app messages, and out-of-app banner messages from Yes on 22 and the tech companies themselves. Such messages, experts say, are legal, though they may not conform with customers’ expectations for privacy.

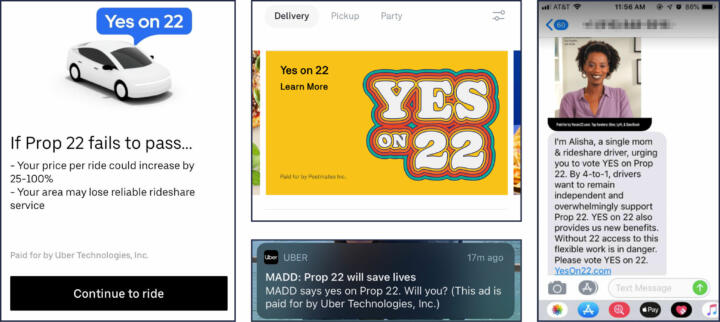

Tristen Miller, a San Francisco Uber customer and opponent of Prop 22, sent a number of screenshots of Uber prompts he’s received, including one that required customers to “confirm” before riding that Prop 22 would prevent prices and wait times from substantially increasing. A banner alert highlighted Yes on 22’s endorsement by Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

Los Angeles Uber customer Jaxson Watts told The Markup that the Uber banner message “was, like, locked, on my home screen, and then it disappeared.” Uber customer and colleague of Prop 22 opponents Hugh Hackett even received his banner message while in Dublin, Ireland. Hackett has not been to California since December 2018.

Jerry Goldfeder, an election attorney at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP, said that by stating within the emails or messages who paid for them and by disclosing them to the state as in-kind, non-monetary campaign contributions, the app-based companies appear to be complying with election and campaign finance laws.

Some California residents also received text messages from the Yes on 22 campaign itself.

Election 2020

Tech on the Ballot in November

Voters in states and cities across the country have had their say on some of technology’s biggest questions

Vetter, the spokesperson for the Yes on 22 campaign, said that all outreach done by Yes on 22 comes from publicly available data such as the voter file, or from people who signed up to learn more about the campaign. “The campaign has not been given customer lists or consumer information from any platform company,” Vetter added.

Los Angeles resident Sandra Madera said she received such a text message from Yes on 22 earlier this month. However, she didn’t recall ever signing up to learn more about the campaign. “[B]ut I’m pretty sure my cell number is on my voter file [because] I receive messages from other campaigns,” Madera added.

Under the recently passed California Consumer Privacy Act, according to Catherine Meyer, senior counsel at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, none of the aforementioned activity is illegal so long as it is disclosed in company privacy statements.

Uber’s privacy policy explicitly states that it may “… send users communications regarding elections, ballots, referenda, and other political and notice processes that relate to our services.” DoorDash’s privacy policy is much more vague: “We may also contact you with promotional offerings or other communications that may be of interest to you.” Both are likely to give the companies cover under the CCPA.

While the targeted messages likely do not violate election laws, Adam Schwartz, senior staff attorney for the Electronic Freedom Foundation, said that the messages exceed principles of privacy rights.

“When a company collects its customers’ personal information for purposes of providing a service, the company should not later use that PI for purposes of targeted political ads,” Schwartz said in an email. “Reports that companies are using their customers’ personal data to send them unwanted electioneering messages are a reminder that our country needs stronger consumer data privacy laws.”