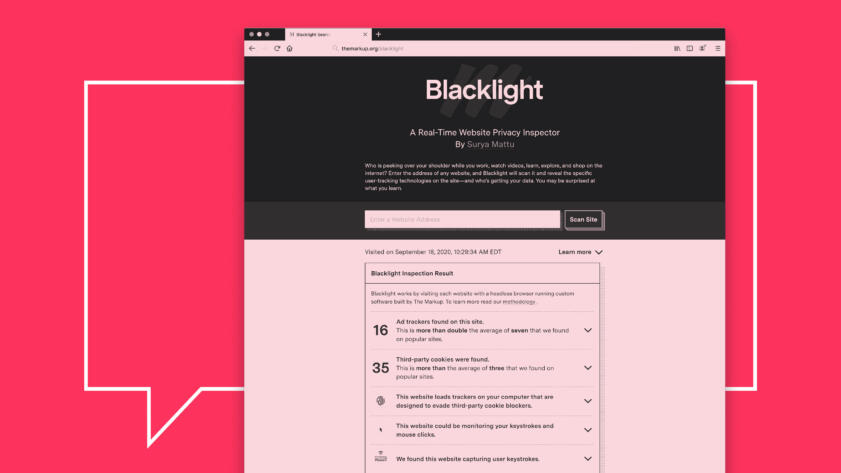

The Markup recently launched Blacklight, a free, instant privacy-inspection tool. Enter any website, and it reveals how you may be tracked when you visit the site, names the companies receiving your data, and explains what the trackers are doing—some of them watch your every mouse move and record your every keystroke. Trust us, it’s more than you’re expecting, raising the question: What can you do about it?

One option is to ensure your web browser is protecting your privacy. In this guide, we’ll walk through some of the different techniques used to track people across the web and detail what each of the major browsers does, or doesn’t do, to circumvent it.

We’ll also add some tips at the end about ways you can slightly alter your behavior to protect yourself.

I’m kind of in a hurry. What’s the bare minimum I need to know?

O.K., O.K. We get it—you’re busy. Here’s the TL;DR:

- Firefox, Brave, Edge, and Safari offer stronger privacy protections by default than you get from Chrome, which is the world’s most popular browser. Tor is the most secure browser, but because of that a lot of sites won’t load properly on Tor.

- You can get extra protection by using privacy-enhancing browser extensions such as Privacy Badger and Ghostery.

- Sometimes using more secure browser settings, or privacy-enhancing browser extensions, means the website you’re visiting won’t work as intended. You may have to bring down protections temporarily for certain sites.

- Sometimes you may not mind being tracked—say you’re couch shopping and really do want to get furniture ads. You can use less secure browsers in those cases, or deactivate your privacy extensions. But if you’re entering medical information or a credit card number on a site, you probably want to use a more secure browser or extension.

I’m worried about privacy, but my friends say I’m always going to be tracked no matter what, so I shouldn’t bother. Are they right?

Not entirely.

A 2018 analysis of 53 web browsers and privacy-enhancing extensions found that, in every case, at least one sneaky loophole remained open for trackers. However, browser privacy protections absolutely can limit how much data about your online behavior your browser spills to ad-tech companies.

For instance, a recent study found a big difference between what advertisers knew about people using Safari, which blocks cookies by default, and Chrome, which does not. The results: 73 percent of ads shown to Safari users were unable to associate the person with an advertising profile, likely because of that blocking, while only 17 percent of ads shown to users of Google’s Chrome browser were unable to associate the user with a profile.

Blacklight

The High Privacy Cost of a “Free” Website

Trackers piggybacking on website tools leave some site operators in the dark about who is watching or what marketers do with the data

While we have you, a teachable moment: a cookie is a piece of data saved onto your device identifying you uniquely, which can only be read by whoever set it—whether that’s the site you’re visiting or a third-party marketing company that sets cookies on millions of sites and uses all that information to build profiles about us all. Some cookies can be useful—for instance, remembering you so you don’t have to sign in every time you visit your favorite site.

Some companies use cookies in concert with another tracker called a pixel, which is a small image or bit of code that sends information about your actions to whoever owns that pixel. If the owner of the pixel has also saved a cookie on your device, your actions on that page can be linked to everything in the profile that the company has already built on you—from your previous browsing history to purchases you made offline.

Having a browser that says, “Thanks, but no thanks,” when a website asks to set a third-party cookie disrupts that process.

Clearing your cookies periodically can also help, though you’ll have to re–log on to some things like your Amazon account or your local newspaper’s site the next time you visit (support local news!).

So ... who blocks cookies?

Mozilla’s Firefox, Apple’s Safari, and Brave all block third-party cookies by default.

When it launched in 2003, Safari was the first major web browser to offer cookie blocking. It now blocks both cookies and tracking pixels by default, according to Ronak Shah, who works in Safari’s product marketing division.

Microsoft’s Edge lets users choose among three levels of privacy protection, ranging from blocking virtually all tracking to letting most of it through. Since blocking trackers sometimes cause sites not to function as intended, this lets users decide when they are willing to sacrifice privacy to be able to use a particular site. When set to “balanced” mode, Edge uses a “site engagement” metric that logs how frequently you use a site, relaxing privacy restrictions for sites you use a lot, under the assumption that you’re more likely to be O.K. with sacrificing privacy for convenience on a site you use regularly.

The Tor Browser doesn’t block cookies, but the browser’s design makes it impossible to link multiple website sessions to the same user, so you can’t be tracked around the internet when you use it, according to Tor Project executive director Isabela Bagueros. Tor is generally considered the most privacy-protective browser, but a good number of websites won’t work correctly on Tor because of its low tolerance for user tracking.

Google’s Chrome, which is currently used by about 70 percent of people around the world, allows third-party cookies by default. The latest version blocks them automatically in incognito mode. Chrome users who want to block third-party cookies can change the browser’s privacy settings, said Google spokesperson Elijah Lawal. Google said it plans to phase out third-party cookies entirely when the industry can agree on a new ad-targeting framework.

However, you can add privacy protecting extensions to Chrome—from tracker blockers, like Privacy Badger and Ghostery, to ad blockers, like uBlock Origin and AdBlock Plus. Each of these extensions rejects certain requests for information when a site asks for data to send to third parties.

Are there times when I want to be tracked with cookies?

Of the many different types of cookies, those set by the website you’re visiting, first-party cookies, are the most likely to be necessary for making the site function as intended (though not all of them are). Because of this, they are not blocked by default by browsers.

HOWEVER, you should know that data collected from first-party cookies can later be added to a marketing or advertising company’s behavioral targeting profile, which has a similar effect to third-party cookie tracking.

Shah, the Safari representative, said that’s why Apple’s browser deletes first-party cookies after a week, to decrease cross-site tracking. Tor deletes first-party cookies the instant you close the browser. Firefox clears out first-party cookies on sites you haven’t interacted with for 45 days.

Chrome and Brave provide users the option to block all first-party cookies in their privacy settings.

Recently, Firefox started blocking a sneaky technique called “redirect tracking” that attempts to use the first-party cookie loophole to secretly load a third-party cookie.

If I’m blocking cookies, I should be safe from all tracking, right?

Oh, you sweet summer child. No one is ever truly “safe” from tracking.

One technique, called fingerprinting, exploits eccentricities in how each computer behaves to identify you—even when your browser blocks cookies.

There are many different types of fingerprinting. Blacklight specifically tests for a technique called canvas fingerprinting, which instructs your browser to write invisible text or draw an invisible picture. Each combination of browser and device will complete these tasks slightly differently, presenting an opportunity for identification.

While canvas fingerprinting can be used for innocuous reasons, like identifying bots, it also has applications for targeted advertising as browser-blocking leads to a decline in third-party cookies’ ability to follow users across the web. The Markup’s scan of 80,000 of the internet’s top websites found that 6 percent used canvas fingerprinting.

Chrome doesn’t block canvas fingerprinting, but Lawal, the Google spokesperson, told The Markup that the company is working on it.

Both Firefox and Brave combat canvas fingerprinting using filter lists, which are registries of domains known to be involved in activities the list creators view as privacy violations. Firefox and Brave scan for scripts by companies that offer canvas fingerprinting and refuse to send those domains any information. Brave also randomizes what a user’s fingerprint looks like as an extra protection against fingerprinters that may slip through.

The Tor Browser has blocked canvas fingerprinting since 2013 using a technique that makes the fingerprinting data difficult for a website to extract from the browser. Bagueros, the Tor Project’s executive director, noted that Mozilla incorporated a modified version of this system into Firefox in 2017.

Safari combats fingerprinting by trying to make each user’s device look as similar as possible, which is easier for Apple than other browser makers because most Safari users are on Apple devices, whereas other browsers are more likely to be running on a wider suite of products.

Microsoft spokesperson Malia Ito told The Markup that Edge blocks fingerprinting “100 percent of the time.”

What about the super creepy stuff? According to Blacklight, one of the sites I visit was basically looking over my shoulder as I used it.

Key logging is when a website logs what you’re typing into a text field before you hit send. There’s also session recording, which is when everything you do on a website—your every mouse movement, every word typed, every click—is recorded and can be played back by the website as a real-time video.

“Collection of page content by third-party replay scripts may cause sensitive information such as medical conditions, credit card details and other personal information displayed on a page to leak to the third-party as part of the recording,” Mozilla privacy engineer Steve Englehart wrote in a blog post. “This may expose users to identity theft, online scams, and other unwanted behavior. The same is true for the collection of user inputs during checkout and registration processes.”

Much like canvas fingerprinting, Firefox uses filter lists to block data from being sent to the most prominent providers of these technologies. In an email, Brave senior privacy researcher Pete Snyder told The Markup that there are instances in which Brave replaces key logger, session recorder, and similar scripts with privacy preserving substitutes.

Ito, the Microsoft spokesperson, told The Markup in an email that Edge “uses disconnect.me tracking prevention list to identify and block session replay scripts as well as malicious tracking types like fingerprinting.”

Lawal, the Google spokesperson, said Chrome does not protect against session recording or key logging. Apple spokesperson Shah explained in an email that Safari allows session recorders, since they’re frequently “beneficial to the user” because they allow sites to better understand how users navigate their pages and consequently improve how they are set up.

I don’t care about advertisers knowing about a lot of my web surfing. Are there times I should be the most careful?

You’ll want to be cautious anytime you’re entering personal data into an online form: your password, credit card number, bank account, etc. For one, you don’t know exactly who’s looking over your shoulder at that website, much less outside of it.

Nandini Jammi, the co-founder of Check My Ads and the ad-tech newsletter Branded, said she was working with a company using a session recording tool and would regularly see people’s personal information pop up in the replays of their interactions with the site.

“I flagged it for my company and they found a way to gray out the credit card/sensitive stuff,” she told The Markup. “The issue is that any employee with access to it can, by default, see sensitive information.”

If you’re entering this kind of personal data, it’s advisable to use a browser or extension that takes steps to prevent session recording.

Facebook and Google trackers seem like they’re everywhere. Are there ways I can get away from them?

One easy step is to not use your Facebook and Google accounts to sign in to other platforms and services. Those social sign-ins may save a few seconds, but they also give those tech behemoths much greater insight into what you’re doing on your linked accounts.

Mozilla also offers extensions for its Firefox browser that limit what Facebook and Google know about you as you move across the web.

Its Facebook Container cordons off your Facebook use from your other travels around the rest of the web, making it more difficult for Facebook to connect what you do outside its walled garden with your activity on the inside.

And Firefox’s Multi-Account Containers extension will do the same for any website, even Google. “You can create a container dedicated to all your Google searches to prevent your search history from being tied to a Google account,” said Mozilla’s Justin O’Kelly. “Also, you could create a separate Google container where you do log in and use Google services that require authentication.”

Can't I just politely ask companies not to track me?

You can. Internet browsers have a “do not track” feature, which is a browser setting that signals to websites and third-party tracking companies that the user would prefer they refrain from collecting the person’s data.

But The Future of Privacy Forum says it has little effect: “Most sites do not currently change their practices when they receive a … [Do Not Track] signal.”

The Digital Advertising Alliance, an industry trade group, offers a tool allowing internet users to opt out of having their browsing history used to serve them targeted ads. Since the group is a consortium representing hundreds of companies, users can opt out of being targeted by all of them with a few clicks.

However, to even get the tool to work in the first place, users have to allow themselves to be tracked by third-party cookies, since those cookies are how the ad-tech companies are able to identify who has opted out. In addition, opting out like this isn’t guaranteed to stop companies from collecting your data; they only promise they won’t use that data to try to sell you stuff.

I want the technical nitty-gritty. Is there a good resource for me to dig into?

We see you. We are you. Head over to CookieStatus.com if you want to nerd out.