Hello, friends,

This week we reported the unsurprising—but somehow still shocking—news that Facebook continues to push anti-vax groups in its group recommendations despite its two separate promises to remove false claims about vaccines and to stop recommending health groups altogether.

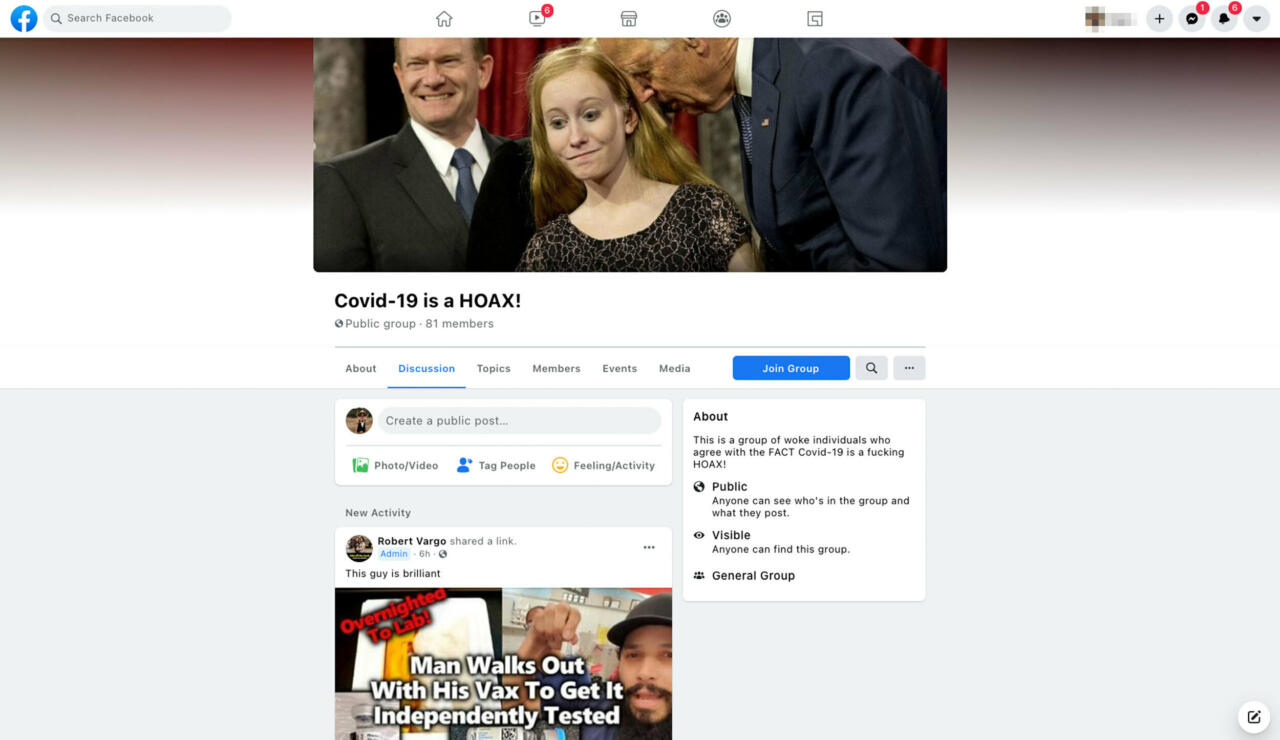

The groups that reporters Corin Faife and Dara Kerr found being recommended to our Citizen Browser panelists were not using sophisticated techniques to hide from Facebook’s automated filters. The groups had names like “Covid-19 is a HOAX!” “Worldwide Health Freedom,” and “VACCINES: LEARN THE RISKS.”

Following its usual playbook, Facebook said it would investigate why these groups slipped through its filters. But the fact that the platform missed such obvious groups raises questions about how well its automated filters are working.

These questions come amid growing concern about the impact of tech platforms deferring to automated systems to police speech across the globe.

Last year, while the pandemic raged, big tech platforms sent their content moderators home and switched to relying more on automated systems. The result was even more uneven enforcement than we’ve seen in the past, according to the companies’ own reports as compiled by the Center for Democracy and Technology. Facebook had trouble catching and removing child sexual abuse material, while removal of hate speech skyrocketed. Last spring, YouTube removed more videos than ever, but a rise in successful appeals suggests that many of them may have been removed in error.

The Facebook Oversight Board—the group that Facebook appointed to oversee its content removal decisions—has repeatedly raised concerns about the impact of using automated content deletion systems to regulate speech.

Last month, in a case that restored a post critical of the ruling party in India, the board urged Facebook to institute “processes for reviewing content moderation decisions, including auditing, to check for and correct any bias in manual and automated decision-making.”

In January, in a case that ultimately restored a post promoting breast cancer awareness that included women’s nipples, the board commented that Facebook’s inaccurate automation “disproportionately affects women’s freedom of expression.” The board added, “Enforcement which relies solely on automation without adequate human oversight also interferes with freedom of expression.”

After all, decisions about which content to delete are inherently political. As researchers Robert Gorwa, Reuben Binns, and Christian Katzenbach wrote in a recent paper on Algorithmic Content Moderation, a perfectly functioning automated system for policing speech would also be dangerous. It “would re-obscure not only the complex moderation bureaucracies that keep platforms functioning, but also threaten to depoliticise the fundamentally political nature of speech rules being executed by potentially unjust software at scale.”

And yet, amid the discussion about the powers and perils of automation, I keep coming back to a simple fact: The mistakes we keep catching Facebook making should be pretty obvious not only to a human inspector but to a well-trained computer algorithm as well.

When Facebook pledged that it would not recommend political groups, all we did to check that claim was pull a list of the top 100 groups that Facebook was recommending to our Citizen Browser panelists. Many of the groups were blatantly political, such as “Candace Owen for POTUS, 2024,” “Joe Biden POTUS 46 Official,” and “The Patriot Room.”

Maybe a computer wouldn’t recognize those groups as political—but only if the computer had not been taught to catch references to fairly obvious political terms such as “POTUS” and “Patriots.” (Facebook ascribed the problem to “technical issues.”)

When we checked whether Facebook was honoring its promise to prevent financial institutions from targeting their ads by age, we simply searched for ads containing the word “credit” or “loan” to see if any of them included age-targeting criteria. And of course, we found ads that violated Facebook’s anti-discrimination promises.

It’s hard to imagine designing an automated system to catch discriminatory credit advertising that doesn’t search the text of the ad for the word “credit.” (Facebook said in its defense that “machines and human reviewers make mistakes.”)

Similarly when we decided to check Facebook’s September promise to no longer recommend health groups, all we did was search the groups recommended to our Citizen Browser panelists for keywords, such as “health,” “COVID,” or “vaccine.”

Once again, it’s hard to image training a computer to not recommend health groups without instructing it to search for the actual word “health” in the title of the group. (Facebook said it uses “machine learning to remove groups that post a significant amount of health or medical advice” and is investigating why some slipped through.)

And so, as much as I am persuaded by those who argue that humans are needed for the most nuanced challenges of content moderation, it seems as if there is a lot of low-hanging fruit that could be fixed by setting some minimum standards for the efficacy and fairness of tech platform algorithms.

The EU is pushing new legislation, the Digital Services Act, that would require the big tech platforms to submit to independent audits of their algorithms. The U.K. Competition and Markets Authority has launched a study of the impact of algorithms on competition. And the U.S. Federal Trade Commission recently warned businesses to make sure their algorithms are not discriminatory.

But so far, of course, there is no regulator who inspects big tech algorithms on behalf of the public the way that, say, the Federal Aviation Administration inspects airplanes for safety. And so, we at The Markup are essentially out on the tarmac inspecting the planes ourselves.

With our Citizen Browser project, we pay thousands of users across the country to install our tool that lets us see what Facebook is recommending to our panelists. Then we comb through the results by hand to see what we can learn about the algorithms. And what we have learned is that they could use some improvement!

As always, thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup