Hello, friends,

It’s hard to be shocked these days about disappointing news about Facebook. Consider this sampling of recent news items about the social media giant:

- A Facebook security vulnerability led to 533 million names, phone numbers, and birthdates of Facebook users being leaked on a hacker forum.

- Facebook temporarily blocked political dissent in India but later said it was a mistake.

- Facebook low-key threatened to start charging for its service if users block it from tracking their behavior on their iPhones.

- Facebook asked its self-appointed Oversight Board to determine whether it should continue to ban former president Donald Trump from its platform, and the board said Facebook was seeking to “avoid its responsibilities” by not establishing clear penalties for violations of its rules.

And that doesn’t count The Markup’s reporting last week that Facebook has continued allowing financial service firms to target credit card ads by age—despite pledging not to do exactly that multiple times, including just a few days earlier in congressional testimony.

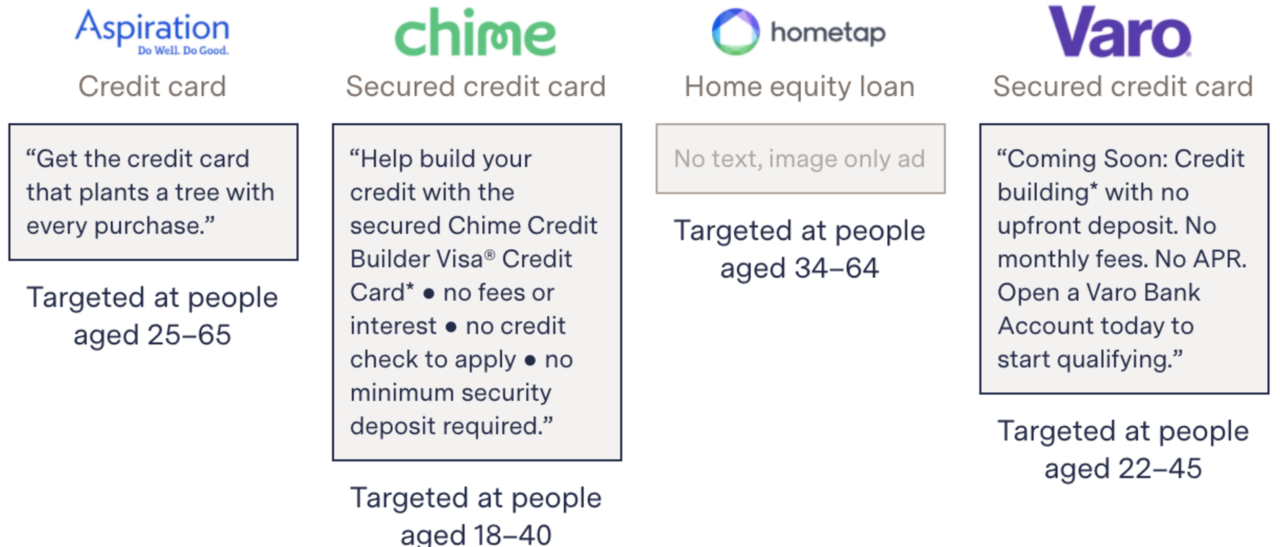

Using data collected from our Citizen Browser project, which has assembled a national panel of Facebook users who automatically share data from their Facebook feeds, data reporter Corin Faife and reporter Alfred Ng found 91 ads from four financial service institutions that were using age-targeting criteria.

Blocking people by age from seeing credit opportunities is a practice that violates Facebook’s anti-discrimination policies and may violate federal or state civil rights laws.

The Markup found ads from four companies falling afoul of Facebook’s own anti-discrimination policies

Targeted ad copy shown to Citizen Browser panelists

Facebook didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment for our story but reached out to The Markup a day after publication to say that it would take action against the discriminatory ads.

“We’re reviewing and removing ads from these businesses that ran in violation of this policy,” Tom Channick, a Facebook communications manager, said in an email. “Our enforcement is never perfect since machines and human reviewers make mistakes, but we’re always working to improve.”

Facebook’s contrite response is no surprise. Like the singing novice Maria in “The Sound of Music,” Facebook often vacillates between insubordination and deepest apologies. Maria’s fellow nuns get so frustrated with her that they sing a famous song: “How Do You Solve a Problem like Maria?”

When considering the problem of how to solve a problem like Facebook, I thought it would be useful to look through the roundup of responses—ranging from defensive to apologetic—that we have received from Facebook in our 14 months of publishing:

Defensive:

- “Given its limited number of participants, data from The Markup’s ‘Citizen Browser’ is not an accurate reflection of the full breadth of people who see ads on Facebook,” Facebook spokesperson Dani Lever said when our Citizen Browser data revealed that official information about COVID-19 safety and vaccines were reaching fewer Black people on Facebook than other demographic groups.

- “It should not be surprising that people with different partisan leanings saw different news sources on Facebook, just as they do with television, radio, and other forms of media,” Facebook spokesperson Kevin McAlister said when our Citizen Browser data revealed the wildly different coverage of the Jan. 6 insurrections that were shown to Trump and Biden voters in our panel.

- Facebook spokesperson Devon Kearns said that the ads we found promoting an inaccurate headline about how a Republican politician “Wants Martial Law To Control The Obama-Soros Antifa Supersoldiers” didn’t violate the company’s rules.

- “This article reflects a misunderstanding of how digital advertising works. All ads, from all advertisers, compete fairly in the same auction. Ad pricing will vary based on the parameters set by the advertiser, such as their targeting and bid strategy,” Joe Osborne, a Facebook spokesperson, told The Markup after our analysis found that Facebook charged Biden, on average, higher ad rates than it charged Trump.

We’re looking into it:

- “We don’t comment on data that we can’t validate, but we are looking into the examples shared,” Facebook spokesperson Katie Derkits said when our Citizen Browser data revealed that Facebook had never labeled any of Trump’s posts as “false.”

- “We have a clear policy against recommending civic or political groups on our platforms and are investigating why these were recommended in the first place,” Facebook spokesperson Kevin McAlister said when Citizen Browser data revealed that Facebook was recommending political groups against its own policy.

Taking Action:

- After asking for multiple extensions to formulate a response, Facebook spokesperson Devon Kearns emailed The Markup the night before publication to say that Facebook had eliminated the pseudoscience interest category that The Markup discovered being used to target ads on the platform.

- “We don’t allow ads with praise, support or representation for QAnon so we have rejected this ad,” Rob Leathern, a Facebook ad executive, said when we found a Facebook ad promoting the QAnon conspiracy just days after the social network banned the conspiracy from its platform.

- “Our goal is to remove hate speech any time we become aware of it, but we know we still have progress to make,” Facebook spokesperson Kristen Morea said after we found Facebook recommending Holocaust denial groups after the company had pledged to remove them from its platform.

- “We’ve rejected these ads as we prohibit content from militarized social movements, Facebook spokesperson Liz Bourgeois said after we revealed that the site was selling ads for merchandise affiliated with a far-right militia group despite having a policy banning militia content.

- “Helping prevent discrimination in employment opportunity ads is an area where we lead the industry,” Facebook spokesperson Tom Channick said after we found an employment ad targeted by race, violating Facebook’s anti-discrimination policies and legal pledges. A week after we contacted Facebook about the ad, it removed race from ad targeting criteria altogether.

Until I compiled this list, I don’t think I had realized exactly how much of our time is spent policing Facebook’s platform. And it makes me wonder how much time and energy the global behemoth is spending policing its own network—or whether it just waits for outsiders like us to do the hard work of catching its mistakes.

Certainly, Facebook doesn’t seem to be spending enough to impact its bottom line. In the first quarter of this year, Facebook’s net income nearly doubled, while revenue rose only about 50 percent over last year’s figures. That doesn’t sound like a company that is pouring money into content moderation. It sounds like a company expanding its profit margins.

Of course, there are multiple lawsuits underway against Facebook—but in the U.S. those efforts are about breaking up the company, not forcing it to better police its platform. Last year, the Federal Trade Commission and a coalition of attorneys general of 46 states, plus Guam and Washington, D.C., filed lawsuits against Facebook alleging anticompetitive conduct. The suits also seek to undo the company’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. (Facebook responded to both suits by reminding regulators that the purchases were approved by regulators at the time.)

Meanwhile, the EU is proposing The Digital Services Act—a new law that would allow EU member states to levy hefty fines on Facebook (of up to 6 percent of annual income) if it fails to remove illegal content or comply with other regulations. (Aura Salla, Facebook’s head of EU affairs, said that the proposed act, along with the proposed EU Digital Markets Act, are “on the right track to help preserve what is good about the internet.”)

But for now there appear to be few penalties for Facebook’s failing to live up to its promises—beyond a bit of shame when we and others call them out. So, we will keep monitoring their actions to make sure that the public knows what is happening in the strangely opaque public square that we call Facebook.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup