The Fuller Project is a nonprofit newsroom dedicated to the coverage of women’s issues around the world. Sign up for the Fuller Project’s newsletter, and follow on Twitter or LinkedIn.

An artificial intelligence (AI) program designed to prevent suicide among U.S. military veterans prioritizes White men and ignores survivors of sexual violence, which affects a far greater percentage of women, an investigation by The Fuller Project has found.

The algorithm, which the Department of Veterans Affairs uses to target assistance to patients “with the highest statistical risk for suicide,” considers 61 variables, documents show. It gives preference to veterans who are “divorced and male” and “widowed and male,” but not to any group of female veterans.

Military sexual trauma and intimate partner violence—both linked to elevated suicide risk among female veterans—are not taken into account.

Recently released government data show a 24% rise in the suicide rate among female veterans between 2020 and 2021—four times the increase among male veterans during that one-year period. It was also 10 times greater than the 2.6% increase among women who never served in the military.

“It was difficult enough to be a woman in the military. We get harassed; we get bullied,” said Paulette Yazzie, a 45-year-old Air Force veteran from the Navajo Nation. She served 13 years in the military, including a tour in Iraq. “Now we’re being pushed to the back—again,” she said.

Yazzie, a former staff sergeant, teared up when informed that the VA’s suicide prevention algorithm prioritized men. She said she faced constant sexual harassment and unwanted advances in Iraq and slept with the light on, the door locked, and a chair propped against it for extra protection during her deployment.

“They always think about us second,” she said. “This is going to cost people’s lives.”

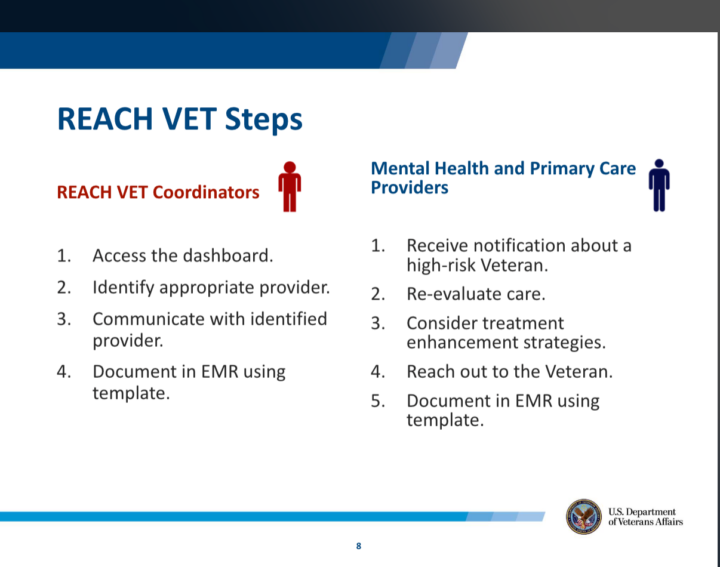

The VA touts its machine learning model, REACH VET, “as the nation’s first clinical use of a validated algorithm to help identify suicide risk.” Launched in 2017, the system flags 6,700 veterans a month for extra help. VA officials say it produces a significant reduction in suicide attempts by those veterans over the following six months.

On May 13, the agency’s undersecretary for health, Carolyn Clancy, called the system a “game changer” during a congressional hearing.

In an interview, Matthew Miller, the VA’s executive director for suicide prevention, said the agency considered military sexual trauma, along with hundreds of other variables, as it crafted its algorithm. But officials decided to exclude a history of rape or assault from the model because it was not among “the most powerful for us to be able to predict suicide risk,” he said.

The algorithm identified being a man, especially a White man, as more predictive of suicide than clinical factors known to impact women, he said. Divorce and death of a spouse were predictive of suicide risk when the patient was male, Miller added, but not when she was female.

The VA uses a national screening program that asks every veteran if they have experienced military sexual trauma. About 1 in 3 women and 1 in 50 men respond “yes,” telling their provider that, while in uniform, they had been forced to endure sexual activity against their will.

“It’s offensive that VA could rationalize overlooking women veterans at risk of suicide,” Allison Jaslow, chief executive of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, said of the algorithm. “This is a very serious issue.”

Though female veterans are the VA’s fastest-growing population, Jaslow said women are habitually ignored. She cited as an example the long, and ultimately successful, fight to get the VA to design prosthetics that fit women.

Meredith Broussard, research director for New York University’s Alliance for Public Interest Technology, said she doubted the agency’s AI system reached accurate conclusions.

Pixel Hunt

Mortgage Brokers Sent People’s Estimated Credit, Address, and Veteran Status to Facebook

More than 200 national and regional lenders share sensitive user data with Facebook. Experts say it might be illegal

“Whenever you have an algorithm that seems to favor the majority group—for example White men—and someone says ‘it’s just math,’ it’s most likely the case where systemic bias is manifesting itself in the math,” Broussard said.

The REACH VET algorithm also fails to take into account whether veterans identify as LGBTQ+, even though the agency’s own researchers have determined transgender veterans die by suicide at twice the rate of cisgender veterans. VA scientists have also found gay, lesbian, and bisexual veterans are at greater risk for suicide than both the overall veteran population and the U.S. population at large.

Though the suicide rate among male veterans remains higher than that for their female counterparts, the rate among female veterans is rising faster. Joy Ilem, national legislative director for Disabled American Veterans, told The Fuller Project she was “puzzled” by the VA’s decision to exclude a long list of factors known to increase suicide risk among female veterans—including military sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, pregnancy, menopause, and firearm ownership.

Ilem noted that the VA’s own researchers have found that risk factors for suicide are different for female and male veterans. Given the rising suicide rate among women, it makes sense to conclude that “something would be included that’s more tailored,” she said.

Still Loading

The Affordable Connectivity Program Was a Connectivity Lifeline for Millions. Congress Is Letting It Die

More than half of the House supports a bill to extend funds. But it can’t get out of committee

The issue of algorithmic bias has gained traction in recent years. Both Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden issued executive orders to promote transparency and accountability for AI products. The VA has identified more than 100 programs covered by those presidential decrees.

Last year, Biden issued two orders that require federal agencies to ensure AI models do not perpetuate discrimination. “My administration cannot—and will not—tolerate the use of AI to disadvantage those who are already too often denied equal opportunity and justice,” he said.

Miller, the VA’s suicide prevention director, said he wasn’t sure what the agency was doing to comply with the orders. A follow-up inquiry to the VA press office did not produce specifics. “The Office of Suicide Prevention is working with the VA AI lead and Chief Technology Officer (CTO) on the development of compliance reviews and monitors,” the agency said in a written statement.

The VA declined to provide data on veterans flagged by the REACH VET algorithm. The agency keeps a monthly dashboard tracking patients and outcomes, but an agency spokesperson said the VA would only share that information if it received a Freedom of Information Act request.

The VA is the nation’s largest integrated health care system, serving 9 million people across 172 hospitals and more than 1,000 clinics. It operates in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Washington, DC.

The number of women using VA services has quintupled since 2001, growing from 159,810 then to over 800,000 today. Women make up 30% of new VA patients, according to the agency.

Veterans in crisis or having thoughts of suicide, or those who know a veteran in crisis, should call the Veterans Crisis Line for confidential crisis support 24 hours a day, 365 days a year: Dial 988 then Press 1, chat online at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat, or send a text message to 838255.