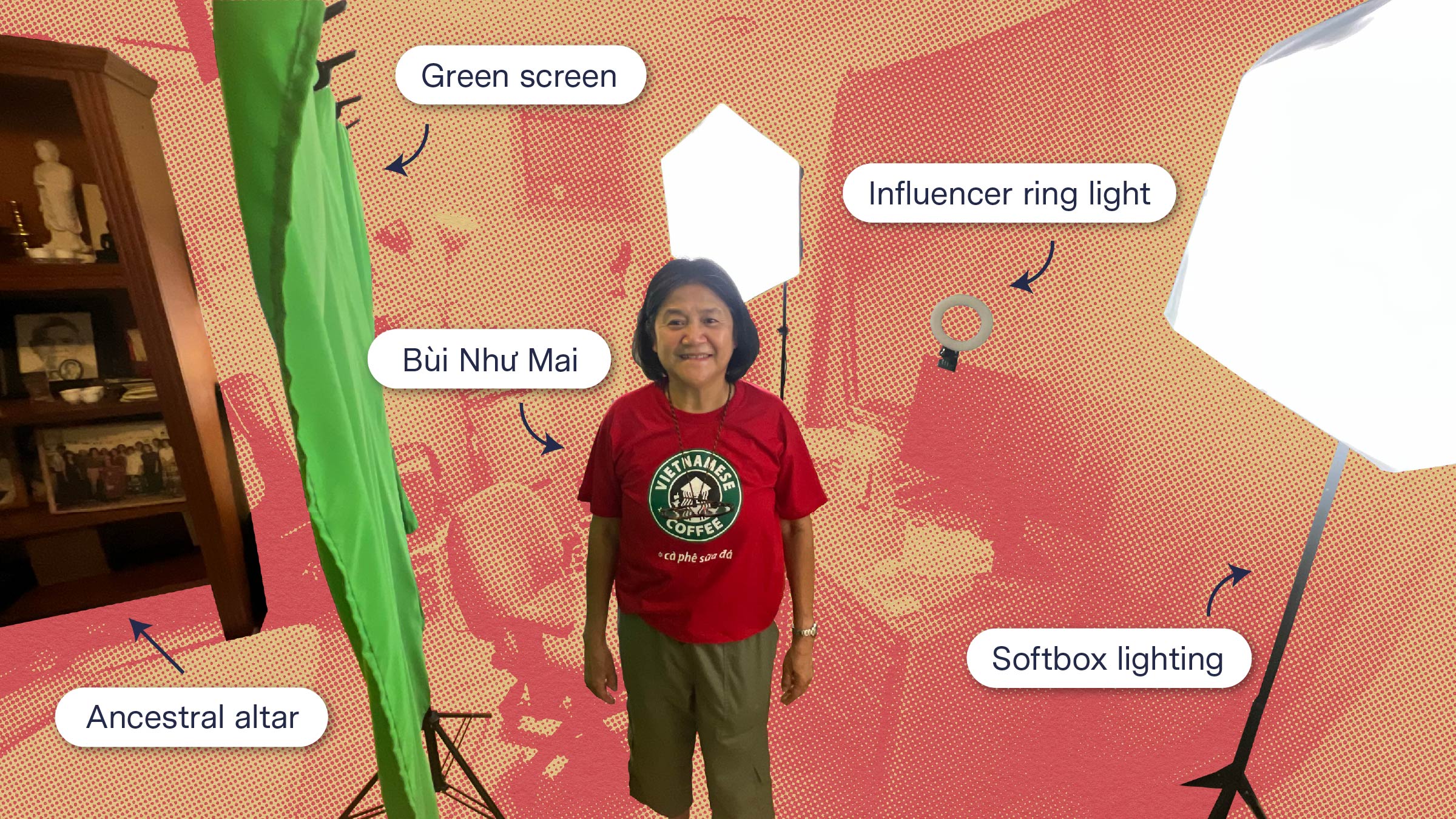

Meet Bùi Như Mai, a 67-year-old Vietnamese grandmother who is also a YouTube influencer.

“I didn’t think I was going to be a YouTube newscaster at the age of 67. But these days you will often see me at my daughter’s house, holding my grandchild while translating articles from Politico or The Atlantic into Vietnamese that I then broadcast on a news channel on YouTube. Every week I try to work my way through two, if not three articles, which takes one or two full days,” said Bùi standing in her kitchen, laughing to herself.

“This is not how I imagined spending my retirement.”

Bùi had noticed a lot of right wing misinformation being spread online by YouTubers in her community, particularly after Donald Trump was elected president in 2016. After she retired from her job as a software engineer at an aerospace company in 2018, she ramped up her efforts to fight back, broadcasting news on YouTube from her home in San Jose, California.

Languages of Misinformation

Vietnamese YouTuber Is Filling Information Voids with Newsmax and Breitbart

How one Vietnamese community depends on YouTube for news, and what that tells us about the unmet needs of immigrant enclaves

Bùi reached out to me after reading my article about the unmet information needs of the Vietnamese community. One of her neighbors sent her the piece and Bùi recognized my name. I didn’t know her, but as it turns out, my dad and Bùi’s husband went to high school together in Vietnam, and have remained in touch.

Bùi invited me to meet with her and three dozen other Vietnamese people she had met from being a YouTuber. A few weeks later, I visited and shared resources on how to combat misinformation in the Vietnamese community. In turn, the group talked to me about how they’re trying to address misinformation, and how, because they don’t speak English, it’s been difficult getting anyone outside their community to care.

It’s one of many reasons why Bùi decided to fight misinformation herself—by translating mainstream news, one YouTube video at a time.

After interviewing Bùi multiple times in Vietnamese, I realized she was giving me her own oral history. What follows is Bùi’s first-hand account of how she often records her videos at 1 a.m., how she was reluctant to be on camera, the friends she’s gained and lost because of Donald Trump, and what motivates her to keep going.

Bùi’s story, as told to The Markup, has been translated into English and edited to reflect the same voice and personality that comes through when she speaks in Vietnamese.

My days are filled with broadcasting news from mainstream U.S. media to my community. I don’t think the Vietnamese people in the U.S. get enough credible news. And I don’t know how to help them get credible news, except that I do the best I can with my videos.

Too many receive misinformation and propaganda, especially about Donald Trump.

I started translating articles in late 2016, when Trump was elected to be President, but I first did so on Facebook. Back then, I was disappointed with the outcome of the elections and I especially didn’t understand how so many Vietnamese friends of mine could support someone who has lied about so many things and who has been such a bully. I had known them for so long and thought we shared the same values. It baffled me to see so much support for Trump on my Facebook timeline from Vietnamese people given how many articles showed his bad behavior in the lead up to the 2016 election.

But I had also realized that many of my Vietnamese friends did not receive particularly well-researched news about the President. At the time, I saw many Vietnamese YouTubers translating news from right-leaning news organizations like The Epoch Times and the National Enquirer that largely praised Trump. In those reports, Trump was lauded as a great businessman. He’s so rich, he must be accomplished, the videos said. He’s also a family man: he has a beautiful wife and good children who behave well. The picture painted of him was that of a successful man with a good family, of someone who is giỏi, which translates to “capable” or “accomplished,” as many Vietnamese describe him.

But that is a completely different picture than the one I got from reading and subscribing to mainstream news organizations like The Mercury News, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Politico and The Washington Post. The picture I saw there was much more complicated. There were reports of him declaring bankruptcy multiple times, of his children almost being charged with fraud, and of his steady stream of lies.

It made me angry to think that so many Vietnamese people in the U.S. were receiving only one-sided information that praised Trump, and believing that was the whole story. I wanted to share the news I was reading with my peers, so I started posting translations of some of the stories I was reading on my Facebook timeline, adding the original story in English at the bottom.

When I was young I would read the newspaper to my father every day because he was slowly losing his vision from glaucoma. Now, I am finding myself in a similar role: I want to bring legitimate news to my community. And once I started posting translations on Facebook, a lot of responses started coming from my Vietnamese circles.

The majority of them were positive. A friend responded to one of my posts saying they learned a lot of English from me. Many people also told me that reading my translations reminded them of when they were kids in Vietnam: The language they spoke in their homes in Vietnam had been standardized by the government over the years and most Vietnamese media no longer use the same Vietnamese we learned as kids. The Vietnamese words I use convey a sense of trust and community for people whose feelings and thoughts are still deeply rooted in their past.

The hard thing for the translation is not the English but the Vietnamese. You have to translate not just the words, but also translate it in cultural ways for the Vietnamese people to relate to it. It’s less about translation and more about interpretation. Sometimes it takes me 15 minutes to rewrite one sentence from English into Vietnamese to get both the gist of the article but to also make sure it sounds like something a Vietnamese person would actually write, say, and fully comprehend.

For instance, I try to use common Vietnamese idioms to help better translate articles. I’ve used phrases like anh hùng xó bếp, which translates to “heroes in the kitchen” and refers to people who talk a big game but only in the safety of their kitchen. Or đầu trâu mặt ngựa, which translates to “head of a buffalo and the face of a horse” and means immoral people.

Of course, posting about Trump also invites a lot of criticism. I was bullied by some of my community members for my translations. Once, a woman who didn’t know me started threatening to beat me in the comments of my posts. She was insistent and would find ways to circumvent being blocked by Facebook—she would purposely misspell Vietnamese words, enough to not automatically be booted off the platform, but their meaning was still clear. My husband thinks she threatened to kill me. My daughters became very worried and one of them ended up reporting the commenter to Facebook.

“I don’t have a face for TV. If I broadcast my face they will just start making fun of me”

After doing these translations for four years on Facebook, I had a steady following, with some of the more popular ones garnering up to 20-30 comments.

Last year I received a call from Ái Vân, a famous singer from Vietnam and a friend of mine who also lives in San Jose. We first met through a mutual friend fifteen years ago and recently became closer friends when she found out I wasn’t fond of Trump. She had recently been recruited by a YouTube show to speak about political issues in the US to a Vietnamese audience. The show is called Người Việt, which translates to Vietnamese People and is separate from a national Vietnamese language newspaper that’s existed since the 1970s. Vân had seen my Facebook posts and thought I should be on their channel, too.

“Absolutely not!” I told her. “I don’t have a face for TV. If I broadcast my face they will just start making fun of me for being old or the way I look, not for what my translations were like.”

But the founder of the channel followed up. He called once. Then another time. Then two more times. Each time I told him “no.” Then he recruited his friend, a mathematics professor at a university in Houston, Nguyễn Dinh Minh Quốc, to try to get me on board. We didn’t know each other, but he called me, still I said no. He called me again, I said no once more.

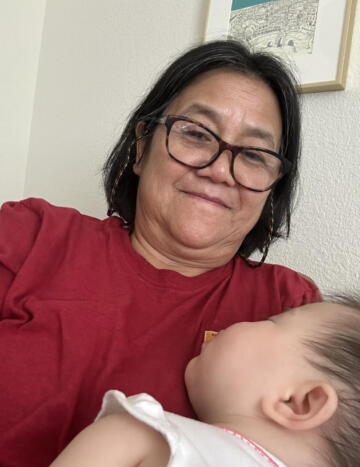

When the professor called me a third time, he caught me off guard: I was taking care of my grandson who was a baby at the time and had been crying all day. I was so exhausted from trying to calm my grandson that I finally relented and said I’d give it a try.

The first time I contributed to Người Việt was them interviewing me on a live stream. The recording stream has now been watched more than 10,000 times. It was a big surprise to me.

The two men running the channel decided then and there that I needed my own show. With the approval of my husband and my daughters, I said yes. The trial run put them at ease and they were excited to call me a Vietnamese influencer.

I now broadcast YouTube videos with news from legitimate news organizations twice a week.

I’m not a journalist and I never have been but I invented a system for me to make it all work. The folks from the Người Việt channel helped me figure out what to buy—a green screen, some lights, a microphone—and I’ve set up a small studio in our Buddhist meditation room. And so I record from that room, staring at my laptop which sits on a stack of books.

Every Monday and Thursday I pick stories to feature on my news videos. Usually it’s current news, like the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. Other times I pick feature articles: once I translated an article about happiness. But there’s nothing that brings in as many clicks among my Vietnamese-speaking audience as stories about Donald Trump. Most of the stories I pick about the former president are critical about him because I know my community is already getting the news that praises him from other channels and because I don’t want him to be re-elected. I get reactions from all kinds of people, many who dislike him but some who support him.

I try to translate at least two stories, if not three, for each video and that can be an arduous undertaking. On weekdays, I start translating a story while I’m babysitting my infant granddaughter. Sometimes it takes me so long to translate an article because I have to go back and forth between taking care of my grand kid and doing this work. Sometimes an article that I like more publishes when I’m halfway or two thirds through a translation, forcing me to start my translation all over again. The average time it takes to record a video is about 3 hours because I have to do multiple takes. Since I do not know how to edit I have to re-record the whole video if I accidentally mess up and say the wrong word. Sometimes I end up working long after I hand my granddaughter back over to her parents and late into the night until 1 or 2 am, just to get the translation right. Even though I worked in an office setting as an engineer for close to three decades in the U.S., there are some articles that really push the limits of my English and I have to ask my daughters for help.

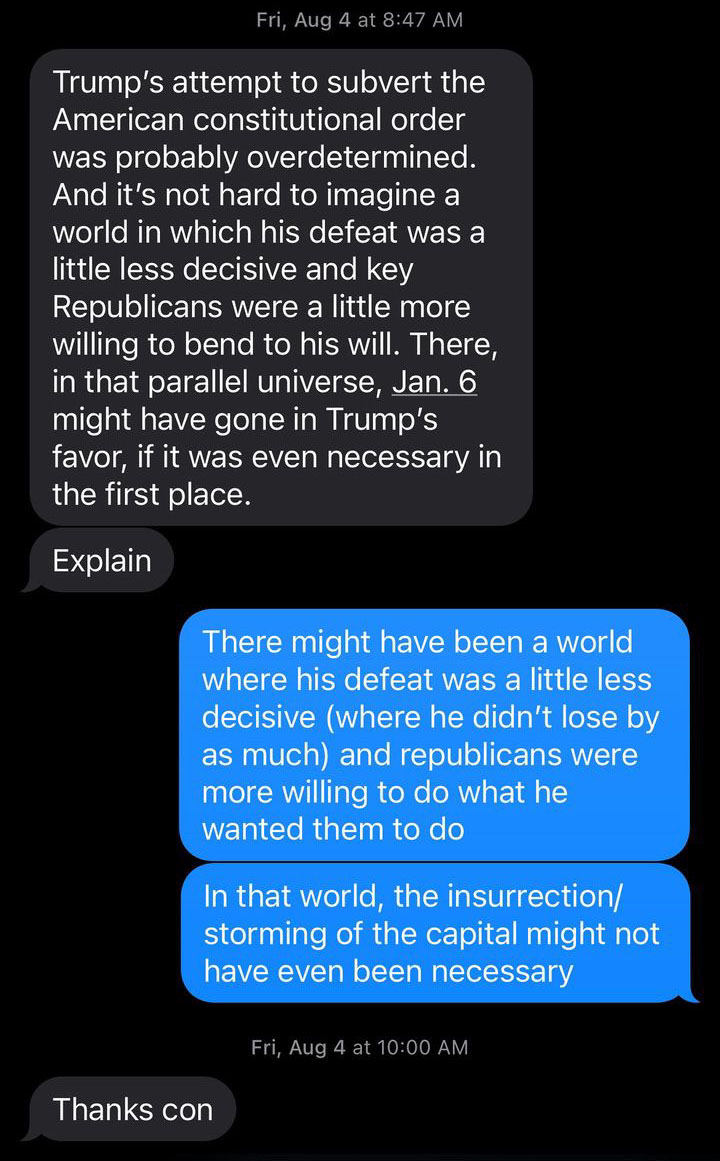

Here is an example of a paragraph in a New York Times piece that gave me trouble:

And even after translating the stories, I still have a lot of work to do. I have to write my introduction for the video and my commentary on the articles. If I don’t get done until late into the night until 1 or 2 am, I usually take a shower, put on the work clothes that I used to wear before I retired, a nice pearl necklace from a collection I’ve put together over the years, and then start shooting my video from my home studio.

A network of friends helping each other

A lot has changed since I started broadcasting news videos on YouTube.

For one, I’m no longer close to friends who are staunch Trump supporters. I know much of the American public was polarized by Trump. And my community is not any different.

But I’ve also found new friends through my work. Over the past two years I’ve met many new friends who are politically active. We talk about thằng Trump—don’t respect him so we call him “boy” Trump, not ông Trump which would be the appropriate honorific. We gather in my backyard for celebrations, have potlucks with Vietnamese food and discuss how we can help our community learn more.

I also have fans now. When I recently announced that I was going on a six week vacation in Vietnam some of my viewers told me in the comments that they were a little sad. Through that announcement video I also learned that I had regular viewers in Vietnam. One of them who lives in the city of Vung Tàu wants to meet me while I’m on holiday.

All of this is tiring work. But at least we do something, rather than nothing.

The other day I was recognized in the parking lot of a supermarket.

“Mai Bùi? Is this you?” The person asked. And my heart stopped for a few seconds. I wasn’t sure if this person was going to yell at me in anger or be kind. Trump has become such a divisive figure in our community, it can be hard to decipher whether someone sees what I do as a threat or as a service.

“Yes, it’s me,” I said.

“I watch you all the time! Thank you for what you do.”

I felt relieved.