Each school day, the students of the John Jay Educational Campus line up outside their squat, brick-lined Brooklyn building and make their way through a metal detector on the way to class at one of the four floors inside.

Isa Grumbach-Bloom heads up to the third floor for classes at Millennium Brooklyn High School. Hajar Bouchour has been learning remotely for a year now, but when she is on campus, she keeps walking, up to the fourth floor, the site of Park Slope Collegiate.

Despite sharing a roof, students’ learning experiences inside can look very different. Millennium has been rated “excellent” in almost every metric set by the city, making it one of the top schools in the borough. Park Slope, on the other hand, mostly garners “good” ratings and occasionally just “fair” for some metrics.

Why students end up at one school instead of another can be a bit mysterious—the product of “screening” algorithms that more than 100 high schools in the city customize and then use to decide which students to admit, often using variables like test scores, attendance, and behavioral records that disproportionately affect students of color. Millennium has chosen to use screens to pick its students, while Park Slope’s high school program does not.

They don’t actually give you why they don’t accept you. They just don’t.

Hajar Bouchour, NYC high school student

Bouchour, who is North African Arab and now a sophomore at Park Slope, applied for admission to Millennium Brooklyn but didn’t make the cut. She wasn’t sure why—maybe the week of school she missed because of the flu in seventh grade. “They don’t actually give you why they don’t accept you,” she said. “They just don’t.”

What both students couldn’t help but notice was how many White students shuffled up to one floor and how many students of color moved on to the others. Park Slope was 10 percent White during the 2019–20 school year, compared to 46 percent at Millennium. “I enjoy most of my classes,” Grumbach-Bloom, who is White, said, “and I think the main thing that’s missing is a diverse group of students in my classes.”

Most media attention has focused on the city’s handful of “specialized” high schools, which admit students based on the results of a single test, called the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT), and which have a history of admitting a dismal number of Black and Latino students. This year, just eight Black students were admitted to the competitive Stuyvesant High School, in one high-profile example.

The controversy has spurred calls to consider other factors when students apply to those schools. But the many screened high schools around the city that already use other factors for admission are also creating apparent barriers for students of color.

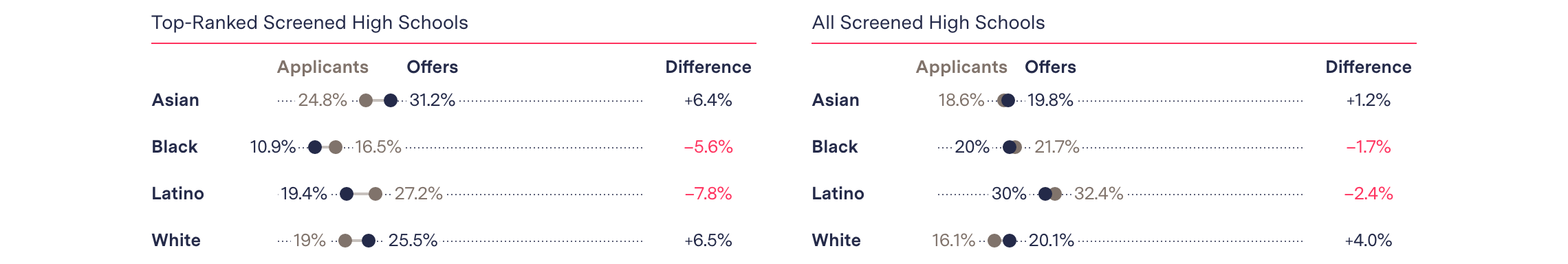

New admissions data obtained by The Markup and THE CITY shows how Black and Latino students are regularly screened out of high schools across New York City—most strikingly, the city’s top-performing schools. While Black and Latino students do apply for admission to these schools, they are consistently admitted at much lower rates than White students and students of Asian descent.

Black and Latino students are frequently filtered out of the top-performing screened schools

Top-Ranked Screened High Schools

Asian

Applicants 24.8%

Offers 31.2%

Black

16.5%

10.9%

Latino

27.2%

19.4%

White

19%

25.5%

All Screened High Schools

Asian

Applicants 18.6%

Offers 19.8%

Black

21.7%

20%

Latino

32.4%

30%

White

16.1%

20.1%

The Markup and THE CITY do not have access to data on the students’ test scores, grades, attendance, or other academic measures used to assess their qualifications for admission in any given school, but the admission rates show clear racial trends.

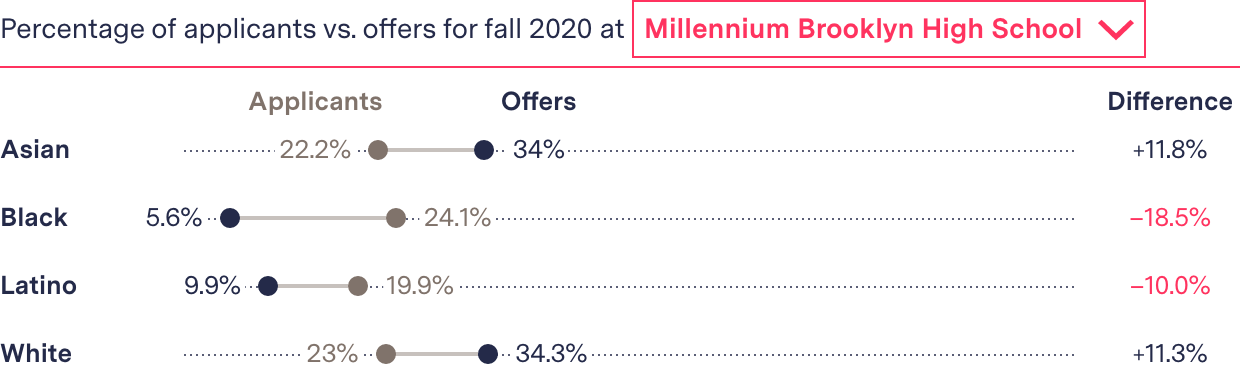

At Millennium Brooklyn, which has been consistently ranked “far above average” in multiple metrics the school system uses to measure success, 24 percent of the more than 5,700 applicants in the 2020 admissions cycle were Black, but Black students made up less than 10 percent of those ultimately admitted. White students? They made up 23 percent of the applicants but more than 34 percent of the offers. That disparity extends across the top high schools in the city. (See our methodology here.)

At Millennium Brooklyn High School, there was a wide disparity between applications and offers for Black and Latino students

Asian

Applicants 22.2%

Offers 34%

Black

24.1%

5.6%

Latino

19.9%

9.9%

White

23%

34.3%

Of the 27 best-performing screened schools in the city, White and Asian students were admitted at almost double the rates of Black and Latino students. While 4.4 percent of Black students and 4.9 percent of Latino students who applied to these schools were accepted, 9.2 percent of White students and 8.6 percent of Asian students who applied were offered a spot.

The school a student is accepted to can mean a major difference in resources and set a student on a different academic path.

Show Your Work

How We Investigated NYC High School Admissions

New York City schools’ extensive use of screens to choose students is cementing segregation

Bouchour couldn’t help but notice the better options Millennium offered in its course catalog. “I saw that they had a lot of AP classes, and they had photography class, and all this stuff. I was like, Whoa, whoa, whoa! That would be so cool,” she said. “And then I was like, Oh, wait, but we don’t have that.”

After years, the schools in the building only recently decided to merge athletics programs—Millennium Brooklyn’s was at one point four times the size of the other schools’.

Pushed by the pandemic, the city has made changes to the process for the next school year, curbing the use of some screens and improving transparency, but experts say it’s nowhere near enough to undo the racism baked into the system.

“We continue to remove barriers and make our school system more equitable, and we’re always exploring ways to build on the promising results we’ve seen already,” Katie O’Hanlon, a spokesperson for the NYC Department of Education (DOE), said in a statement. “The recent admissions changes are driven by the best interest of our students and, while we know there is more work to do, we won’t stop working to bring real, lasting change to our public schools.”

School screening has become a part of segregation in the city that goes well beyond education, said Johanna Miller, an attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union, but one the city has in its power to change. “It’s the primary driver that we have to grapple with as a city,” she said. “In our opinion, it’s also the most clearly wrong policy choice that the city has made.”

Black and Latino Kids Are Screened Out of the Top Schools

In 2014, a bombshell report from the University of California, Los Angeles, found that New York City had among the most segregated schools in the nation, and since then, the city has been forced to look for answers on just how the situation turned so dire.

Like other American cities, schools in New York have a long history of residential segregation to reckon with, but one contributing factor has stuck out: New York City’s intense admission process for public high schools.

This year, as it has in the past, the New York City 2021 high school admissions guide reached near-phone-book length, almost topping 500 pages. Schools have wide latitude to make decisions about admissions, and even if families are dedicated to learning the exact requirements for different schools, it’s not easy to find them. For a 2019 Fordham Law School study, researchers scoured web sites and contacted high schools directly to find the exact admissions criteria for 157 screened programs. They got just 20 responses back.

“That’s one thing about New York is that the screened and audition programs, they pretty much rank students however they see fit,” said Sean Corcoran, an associate professor at Vanderbilt University who’s tracked data on admissions in New York City schools for years. “There’s no uniform formula that schools use across the city, so you never know what’s happening behind the curtain of these screening programs.”

Students rank up to 12 schools when applying and are then matched by computer. At any one of those schools, a formula might rank students with a score calculated through something like, say, 40 percent test scores, 30 percent grades, and 30 percent attendance. But the variables, and how much they count for, can vary wildly. Some screens are complicated algorithms that set rigorous requirements for entry—high test scores, consistent attendance, excellent grades.

Other academic “screens,” as some scholars have pointed out, are almost meaningless. Students with barely passing grades, or even below-grade-level test scores, can still be admitted. Some more targeted “screens,” like an audition for a dance-focused school, are less controversial.

Some studies and reports have looked at whether screening disadvantages students of color more than other ways of picking students. A local student advocacy group, Teens Take Charge, also published some related data late last year on admissions rates as part of a U.S. Department of Education civil rights complaint on screening practices in the city.

The Markup and THE CITY wanted to know precisely how many students were pushed out of every school by the screening system—and where the gaps were the largest.

There are 75 non-specialized high schools that select all of their students with a screen, and through a public records request to the NYC Department of Education, The Markup and THE CITY obtained the number of students of each racial demographic who applied to every screened school for the fall 2020 admissions cycle versus how many were accepted.

8%

of Black applicants accepted to one Queens high school, compared with 35 percent of White applicants.

Portions of the dataset that involved very small numbers of students were redacted to protect students’ privacy, and the data didn’t include racial data about applicants coming from private schools. Beyond the 75 schools we looked at, there are dozens more that select some of their students with a screen and others without one. But to focus on the effects of screening specifically, our analysis only tracked completely screened schools.

We also looked at recent achievement metrics for each of the schools, using New York City schools data, and found that screened schools with some of the high rankings for metrics like four-year graduation rates, access to advanced courses, and math and English test scores, were more likely to use screens that disproportionately accepted White or Asian students.

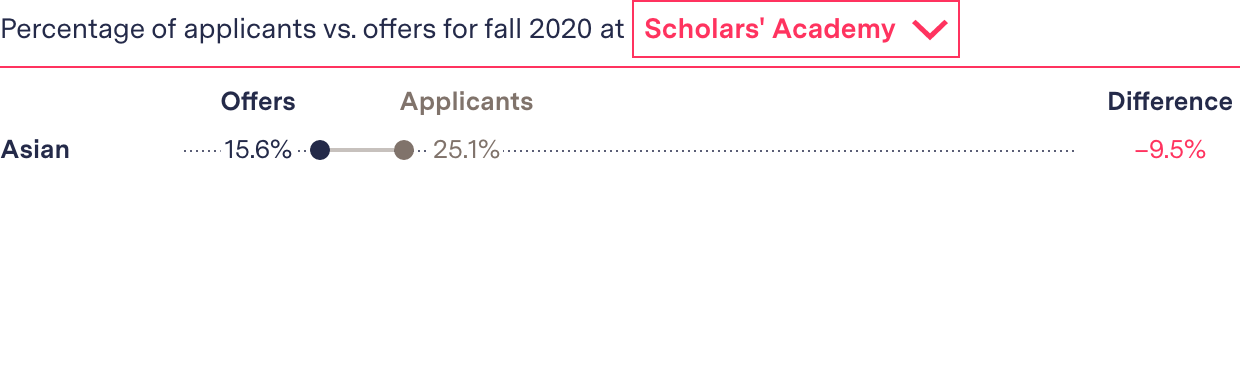

Take the Scholars’ Academy in Queens, a top-ranked school that stood out in the data for its admissions gaps. Nearly 300 White students applied, and 103 got in—an acceptance rate of about 35 percent. Slightly more Black students, 315, also applied—but only 25 received offers, an acceptance rate of around 8 percent.

The principal of Scholars’ Academy didn’t respond to a request for comment.

At Scholars’ Academy in Queens, White students had a much higher offer rate than other demographics

Asian

Applicants 25.1%

Offers 15.6%

Black

20.6%

12.6%

Latino

22.7%

18.1%

White

19.4%

51.8%

The mayor’s office has the broad authority to decide whether schools can use screens or whether to allow only specific types of screens. Right now, though, schools have been given wide discretion over what their screens look like.

O’Hanlon, the Department of Education spokesperson, told The Markup that the city has prioritized community engagement, including with disadvantaged families, to build a fairer process. But the data shows the potential limits of engagement alone. A similar number of Black and Latino students applied to the best-performing schools we looked at, compared to other demographics. They were just less likely to get in.

The city and state have also provided funding to some districts to develop diversity initiatives, O’Hanlon pointed out. More than 100 schools are part of the city’s “Diversity in Admissions” program, in which schools pledge to give priority to disadvantaged students. But only 10 of the 75 screened schools we looked at were part of the program during fall 2020 admissions, according to city data.

Defenders of the system argue that the algorithms are simply measures of academic strength. But the families with the most resources, those in favor of reform say, are better positioned to navigate every part of the admissions system. They can hire tutors, get test prep, learn about admissions to the best schools through networking, and have the means to make sure their kids get there on time.

Many of the admissions criteria are beyond a student’s control. Until this year, if a student lived in a different district, in order to attend a well-ranked school in a largely White neighborhood, that student may have had to contend with the hurdle of a high school geographically preferencing some students for admission. Black and Latino students are also more likely to suffer from some chronic health conditions, which might affect middle school attendance records. Advocates say other potential screening factors, like behavioral records, are also prone to bias against students of color.

Screening didn’t bring racial segregation to schools in the city—schools were segregated well before the system was in place. But it has further separated students by their records of achievement and put in new barriers that reinforce an already racially divided system.

“The way I always think about this is, the legacy of racist housing policies laid out the groundwork for segregation,” said Matt Gonzales, director of the Integration and Innovation Initiative at New York University’s Metro Center. “The school admissions policy, particularly the most egregiously racist ones, basically uphold and reinforce and replicate those patterns of segregation.”

That system doesn’t ensure certain students won’t succeed, but, he said, it effectively stacks the deck against them.

Eliminating the “Low-Hanging Fruit” of Racial Discrimination

Late last year, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced changes to the screening system in the city. Middle schools, he said, would “pause” using screens for the upcoming school year and re-evaluate the following year. All high schools, he announced, would permanently phase out the use of geographic preferencing, which favors admission for students living in certain parts of the city and can disproportionately lock students of color out of schools in White areas.

Eleanor Roosevelt High School, for instance, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, which has been ranked as “far above average” by the city in metrics like four-year graduation rate and math test scores, had prioritized admission for students living in District 2, an especially White, wealthy part of the city.

For fall 2020, the school offered slots to 345 students. While 26 percent of the applicants vying for a slot were Latino, less than five percent of the offers went to those students. The exact number of Latino students that eventually got through the screen was redacted in the data because the DOE claimed that releasing it would violate students’ privacy.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s principal did not respond to a request for comment.

High schools, however, will be allowed to continue using other screening metrics.

There will also be more transparency: Schools are now required to publish their screening requirements on a centralized city website.

We don’t think, at any scale, the best and most supportive and most well-resourced schools should be something that everyone doesn’t have access to.

Johanna Miller, New York Civil Liberties Union

“Getting rid of the geographic screens was sort of the low-hanging fruit,” Miller said. But she adds that “we want to see public schools be a public resource.”

“We don’t think, at any scale, the best and most supportive and most well-resourced schools should be something that everyone doesn’t have access to,” she said.

Others haven’t been so pleased. Some parents have argued that students who work especially hard or perform especially well should be placed together in schools where they can get advanced learning. After the announcement, one parent advocate told the New York Post there was “a sense that there is no regard for even pretending to maintain academic excellence and that they are more concerned about optics.”

The decision was largely driven by the pandemic, which caused schools to temporarily abandon measures of success like test scores and attendance for the year, and, depending on your view, forced school officials to overhaul the system or gave them a politically viable reason to do so.

Announcing the changes, Richard Carranza, de Blasio’s recently departed schools chancellor, explained that the plan would “address the current circumstances attendant to the pandemic.” It particularly wasn’t viable to screen middle school kids based on pandemic attendance and grades, especially when state test exams were canceled for the year. “We’ve had to re-invent the building blocks of public education in the nation’s largest school system from how to go to class, to a grading policy, attendance and everything in between,” he said.

There have been some signs of success. Early data, the city recently announced, showed that low-income students were receiving more offers to competitive middle schools, compared to past years.

At Eleanor Roosevelt, the Department of Education said in an email, the removal of geographic barriers made a big difference: More than 60 percent of offers went to students outside of District 2, compared to one percent the previous year.

Admissions for students who are eligible for free and reduced lunch also tripled this year—from 16 percent to 60 percent. That might be partly because Eleanor Roosevelt started participating in the Diversity in Admissions program this year, which prioritized those students for 38 percent of offers.

The city hasn’t yet produced racial data on schools for the year.

How lasting those changes are may hinge on the winner of this year’s mayoral election, which will determine who takes authority over school screening policy.

“This is an administration that’s on the way out, so they basically punted to the next administration and said, We’re going to pause for a year and then let whoever else comes in figure it out,” Gonzales said.

The data The Markup obtained shows how many students were eventually turned down by the system, but what it can’t show is how many students felt out of place in the system even when they succeeded.

Stephanie Chapman, who is Afro-Latina, is a high school junior who went to a middle school in the Bronx. “It was a low-income neighborhood; we barely had any funding,” Chapman said. “We had half of a floor—literally our school was half of a floor.”

When she was looking for high schools, she decided to take the SHSAT for entrance into one of the school’s elite specialized schools. She got a seat at one but worried with her background she wouldn’t fit in. “I just didn’t want to go, because I felt imposter syndrome,” she said. “I felt like I didn’t deserve to go.”

She ended up going to Bard High School Early College Queens instead, a screened school that’s been great for her. She’s on her way to getting a college associate’s degree there, and the faculty goes above and beyond to help with anything students need.

But she’s had to take some time to adjust. Other students would talk about going snowboarding over the weekend as if it were a regular activity. She had a hard time relating. “Growing up in the Bronx, my school, we were all pretty low-income,” she said. “Just to see the shift in people and their economic stance was kind of a shock.”

Bard Queens’s principal didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“Not all people are test-takers, not all people are interview people, not all people have the same access to things,” said Bouchour, the Park Slope Collegiate student. “It’s just not fair how you judge someone based off that stuff and you know absolutely nothing about their story.”

This story was produced in collaboration with THE CITY, an independent nonprofit news site that serves the people of New York through hard-hitting journalism.