Hi, readers!

I’m Monique, an investigative reporter at The Markup and now on the i-team at CalMatters (if you’ve been offline this summer, we combined our newsrooms). I’ve been covering technology at the intersection of immigration, criminal justice, social justice and government accountability. This week, I’m introducing you to Francisco Lara-García, a sociologist at Hofstra University, to unpack how surveillance has evolved, and its relationship to folks, like himself, who call the towns, cities, and municipalities along the southern border home.

One of the first words Lara-García learned to say was “sapaporte,” which, when decoded from little-kid-speak, was his attempt at the Spanish word for “passport.” It was a pretty advanced concept for the then-four-year-old. He knew the booklet was a lifeline, and that he needed this thing to be able to cross to and from—that it was a non-negotiable.

Today, Lara-García studies immigration at the intersection of urban studies. Apart from his academic research at Columbia, Princeton, University of Arizona, and Hosfra, it was his personal experience with border surveillance as an everyday citizen that piqued my interest. He’s lived most of his life in towns along both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border, including the Mexican towns of Tijuana and Sonora, and Tucson and Nogales, Arizona.

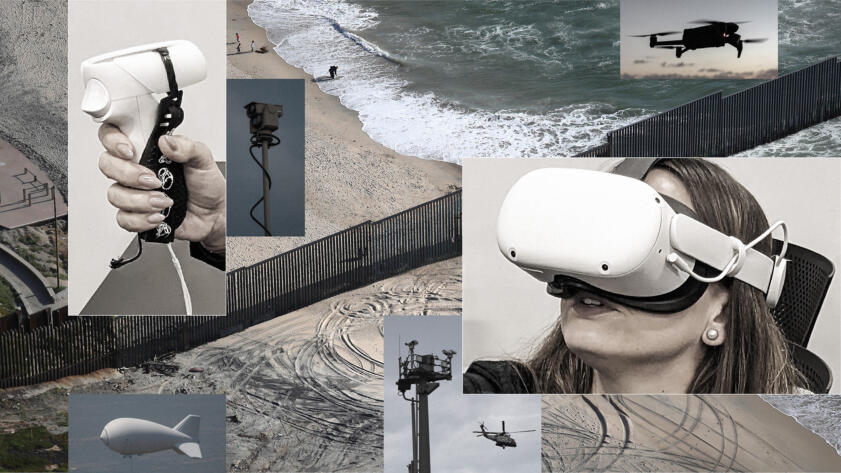

We’re both struck by how quickly these technologies become an unremarkable part of daily life. Over the last four decades—particularly after September 11—surveillance has drastically evolved. It goes beyond basic monitoring tools like border checkpoints, physical patrols, and “sapaportes.” As of July 15, the Department of Homeland Security has planted 479 surveillance towers along the southern border, according to data compiled by the Electronic Frontier Foundation. The “virtual wall” makes its way from the California coast all the way down to the lower tip of Texas.

Now, everyday communities are almost numb to the persistent and pervasive presence of government- and privately-funded technology like autonomous towers, aerostat blimps, sky towers, incognito license plate readers, and biometrics. The rapid growth of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms that study their every move is the new normal.

“I actually think if you ask a lot of people that live on the border, they’ll tell you that as far as surveillance, that they’re not being surveilled, or that they don’t notice the surveillance or that surveillance is kind of not important to them,” Lara-García told me. “And I think that is part of the reality of just living in these communities: It’s not that important to them because they’re so used to it or because they don’t notice it.”

My conversation with Lara-García has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Lara-García: One thing that is kind of a paradox about living and having lived on the border is that there are moments when you can’t not be aware of the intense amount of enforcement and surveillance and activity across the border. But at the same time, it also just becomes a fabric of your life that you don’t notice, or you just don’t pay attention to it. Part of that is because it gets normalized, but also sometimes because there’s surveillance and enforcement that actually just doesn’t impact your life at a particular moment.

That is twofold for people, who unlike me, don’t cross into the U.S. or Mexico regularly. And so for those people who don’t have activities that bring them across the border, the way that they physically experience surveillance and enforcement is less, or at least seems to be less.

Madan: What does that look like? A giant blimp hovering over your community?

Is it an automated license plate reader? Is it a mobile camera towering over their community? Is it a mixture of them? What does surveillance look like in practical terms?

Lara-García: I vividly remember the helicopters. I lived in Playa de Tijuana growing up, and that’s right across—you can see the border wall very closely. So you would see the helicopters flying across, and you would hear them at different times of the night. Sometimes, it would be more active. You can look across the wall and just see the border patrol cars. But yeah, you can also see these digital technologies. The digital technologies that you encounter, at least in my experience, are typically only visible when you get very close to the border crossing point.

The thing that can be unsettling is that there are so many ways that you are probably being watched. You’re aware that you’re being watched, but you can’t see it with your eyes. But you have no idea what they’re actually able to see and what they know about you. And so the forms in which you don’t know how you’re being watched, or you don’t know what information they have on you, is part of the unsettling experience of living on the border.

Madan: Has that been your experience just on the Mexico side, or also on the U.S. side?

Lara-García: I guess I should be clear that for the most part, in my experience, going from Mexico into the U.S. is where you feel the intensity of that particular type of surveillance. Going from the U.S. into Mexico is a much easier experience. And it’s because, you know, the Mexican government doesn’t have capacity or necessity to create such digital infrastructure for surveillance.

Madan: What if you were to strip out the component of crossing to and from via border checkpoints? What about just daily life? You’re at your home on the U.S. side, going to the doctor, the grocery store. Talk to me about surveillance on that type of level.

Lara-García: I would say that it depends on where you are. So let’s say you are in Nogales, Arizona, which is right across the border wall. You see the border patrol driving in your neighborhood. You see helicopters flying right on top of you. Sometimes they’re actually searching for people, so you can see the process of pursuit. The chip readers are there but invisible. My parents live pretty close to the border wall, and sometimes they go driving to the desert. It’s public land. And then sometimes you’re out there hiking, and then all of a sudden, border patrol comes. They start asking you all of these questions about what you’re doing there, why are you going there. It’s public land. There’s no reason why someone who lives in the neighborhood shouldn’t be able to go.

News

The Future of Border Patrol: AI Is Always Watching

Human rights advocates warn of algorithmic bias, legal violations, and other dire consequences of relying on AI to monitor the border

And so, you know, there are two questions, right? One is, how do they know where I am? How did they see me? And the second thing is, like, well, you know, I’m entitled to be here… So that’s what it’s like living close to the border.

Madan: How do you think surveillance shapes the settlement patterns and community formation of migrants in border cities? Is that part of your research at all?

Lara-García: I can speak on this as someone who is very familiar with the history of the border, and this is part of my academic expertise. One of the things that you can see about the settlement patterns of cities on the border is that cities on the border grow because of the creation of the border. If you look at most of the contemporary settlements that are right along the border, they’re about 100 years old. They’re actually the product of the end of the Mexican-American War. The borderline was drawn and then these settlements emerged. This is a case of cities like Tijuana, Nogales, Mission, McAllen, Reynosa. The one exception, the one city that actually predates the existence of the contemporary border, is El Paso. El Paso was a settlement that existed before this period, before the Mexican-American War. As the border has become a zone of more intense enforcement, those cities have kind of incorporated those enforcement infrastructures.

It’s hard to say exactly how surveillance shapes the specific settlement patterns, but it’s to say that the creation of this border, which was supposed to divide communities and make sure that people knew what nation-state they were in, is the thing that shaped, actually, the origin of most of those very cities. Most of the economies and the activities of the cities along the border are oriented towards being able to cross and move things across the border. And so, that enforcement line is important.

Madan: How has surveillance infrastructure transformed urban spaces in border cities? Do you see it?

Lara-García: You absolutely see the transformation of urban spaces in ways that want you or allow the government to surveil you more effectively as you’re approaching the border. So the thing that’s interesting, the way that you really, really see this is because they want to get a read on who you are. They move and they shape or change the road systems in such a way that you can’t avoid being surveilled.

Madan: What would you say are some of the most invasive surveillance practices that you’ve observed?

Lara-García: Personally, the thing that is most unsettling is: the ways that you don’t know that you’re being surveilled. It’s the feeling that, at any given moment, there is something or someone watching you to check if you’re doing something wrong.

Again, an example, you’re going for a stroll in your neighborhood, and all of a sudden the Border Patrol shows up and starts asking you questions, right? You’re taking a walk in your neighborhood where you live. And then, of course, they’re probably pulling you over because of the way that you look. If you’re someone like me, who’s Mexican, you know, you can’t help it. And they probably are racially profiling you. You fit a profile and they think that you’re suspicious, even though you live in the neighborhood, and you’ve lived there longer than any of them have ever even been posted at the border. So to me, that’s the most unsettling form of surveillance. It’s the way that you don’t know that you’re being watched.

Madan: How does this type of surveillance practice affect the daily lives of everyday border residents?

Lara-García: There are two sets of people. A person who has economic resources, who’s educated, who is able to get the documents that allow you to cross and has a necessity and a desire to cross routinely. What’s also true is that there are subsets of people who don’t have as much exposure or necessity to enter the field of surveillance as often, right?

There are people who might have, like, a commercial visa, who come to the U.S. a couple times a year just to do shopping for Christmas. And then there’s also the subset of people on the border that don’t ever cross, right? Sometimes, the surveillance is kind of not important, or they don’t ever experience it at all. And part of that is actually because they are being surveilled less because they are people who cross less, they’re of less interest to the entities that are interested in collecting your information.

But on the other hand, if you’re a border resident, all of these activities become normalized. There’s something that just becomes a daily part of your life. So you see the blimp, and you’re like, “Alright, well, there’s a blimp. It has really no effect on my life.” Or, you know, the border patrol driving by. “Well, you know, they do that 10 times a day. So, like, I don’t care about that.”

Hello World

A Virtual Reality Tour of Surveillance Tech at the Border

A conversation with Dave Maass of the Electronic Frontier Foundation

Madan: I’m curious if your current research intersects at all with surveillance, specifically?

Lara-García: I don’t specifically study surveillance. But one of the things that my research touches on is describing and narrating the daily experiences of immigrants. And so to the degree that they are concerned about the tools that the government uses to make their legal status known to deport them, these things come up.

One thing I can say is that immigrants, especially those that are undocumented, are always aware of their legal vulnerabilities. There’s this great book written by Asad L. Asad called “Engage and Evade: How Latino Immigrant Families Manage Surveillance in Everyday Life.”

One of the things that he talks about is how we talk about immigrants trying to evade surveillance routinely. The flip side of this is that there are also lots of immigrants trying to engage, who are working to allow themselves to be surveilled when they are doing good things. So they want to be essentially seen by the state as being people who are productive, contributing members of society. And so that’s the flip side.

Madan: How do you think this type of surveillance influences people’s trust in the government and law enforcement? Given your experience, has it eroded any trust you have, having lived in so many places along the border?

Lara-García: This is me putting on my sociologist hat. There are lots of studies that show that when there’s increased enforcement, that leads to decreased trust. There are also studies that show that when there is increased enforcement, and there’s specifically increased immigration enforcement, people are less willing to go to the police to report things. So there’s empirical evidence to show that when there is increased enforcement, there is also eroded trust and the ability of institutions to respond to actual real problems.

Madan: From your research, what are the most significant findings regarding the intersection of migration, urban sociology, and surveillance?

Lara-García: My research hasn’t looked specifically at changing enforcement regimes in the U.S., but I think one thing that we do know as immigration scholars is that there’s increasing attempts to to have internal enforcement of immigration. And in order for that to be accomplished, they’re using and deploying different types of surveillance technologies. As there becomes more political desire to monitor the whereabouts of particular people, there is deployment of new technologies to keep track of where they are. So, like, the ankle monitors that they put on asylum seekers after their cases have been heard is an example.

But historically, the largest and most intense sites of surveillance tend to be closest to the border. The worrisome tendency is when those start to expand and extend inward. And so places where there was no known immigration enforcement before might become sites of immigration enforcement surveillance in the future. The government has collected and has good records of individuals, like biometric reads. There is a very possible future where they could use cameras on the subway to try to find someone who is undocumented, and that’s a really scary prospect.

I think there’s lots of potential for these technologies to be deployed in ways that will make the experience, specifically of immigrants, worse. But, you know, the potential exists for lots of populations.The potential for specific harms for immigrants exists, but also the harms exist for the general population in all sorts of different ways.

***

Lara-García is just one of many academics, experts and sources who I’ve spoken to as I continue to investigate surveillance at the southern border. If you’d like to contribute to my reporting by way of any insight or tips, please reach out. And yes, I take snail mail, too!

Monique O. Madan

(786) 369 – 6249

P.O. Box 832155

Miami, FL 33283