The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection is trying to build AI-powered border surveillance systems that automate the process of scanning people trying to cross into the U.S., an effort that experts say could push migrants to take more perilous routes and clog the U.S. immigration court and detention pipeline.

To achieve full autonomy across the borderlands, CBP held a virtual “Industry Day” in late January, where officials annually brief contractors on the department’s security programs and technology “capability gaps.”

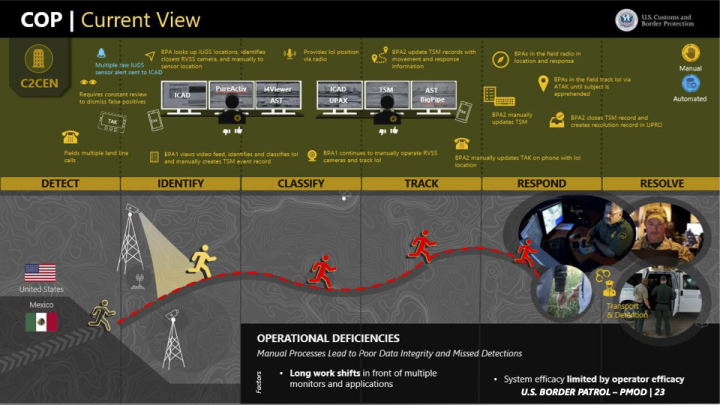

One of the main shortcomings: too many missed border crossing detections because border agents spend long work shifts in front of computers.

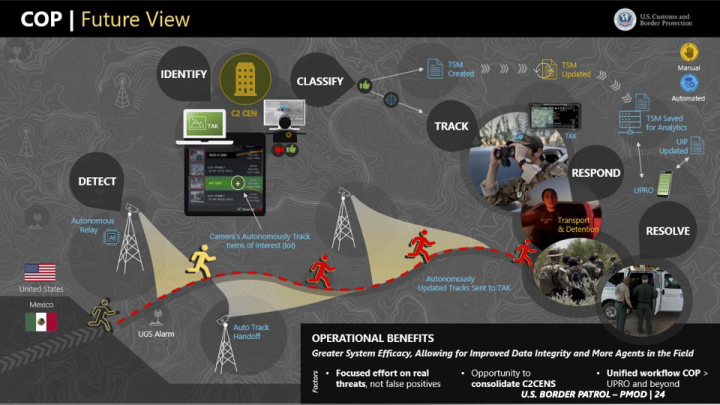

Presentations and other materials shared at Industry Day are public record, but they are geared toward third-party contractors—and often go unnoticed. The Markup is the first to report on the details of CBP’s plans.If all goes as hoped, then U.S. Border Patrol “operators would need only to periodically monitor the system for accountability and compliance,” officials wrote, according to meeting documents.

Currently deployed surveillance technology relies on human staff to observe and relay information received from those technologies. Investing in tech that’s not AI-driven would increase the number of people required to monitor them around the clock, officials wrote in a 2022 document that was shared at the event, adding, “New autonomous solutions and enhancements to existing systems are therefore preferable and are expected to reduce the number of personnel required to monitor surveillance systems.”

Some of CBP’s goals include:

- Creating one unified central operating system for all land, air, and subterranean surveillance technology

- Upgrading fleets of mobile surveillance trucks

- Integrating persistent, real-time surveillance in remote locations

- Reducing costs and human operator dependence

- Minimizing margin of error and missed detections

- Maximizing use of AI to flag illegal border crossings in real-time

- Investing in technology that would navigate terrain and surveil moving “items” or people

- Fully autonomizing surveillance so that more agents can be placed in the field to apprehend, transport and detain border crossers

Currently, only one out of 12 components used by CBP’s Command, Control, and Communications Engineering Center—the technological hub for everything the agency does along the border—is autonomous, records show. Once the department reaches its goal, nine out of 12 would be automated, according to an analysis by The Markup.

The main goal is to hand off surveillance decision-making to AI, largely eliminating the human element from the point a person crosses the border until they’re intercepted and incarcerated.

Since at least 2019, DHS has been gradually and increasingly integrating AI and other advanced machine learning into its operations, including border security, cybersecurity, threat detection, and disaster response, according to the department’s AI Inventory. Some specific uses include image generation and detection, geospatial imagery, identity verification, border trade tracking, biometrics, asylum fraud detection, mobile device data extractions, development of risk assessments, in addition to more than four dozen other tools.

“For 20-plus years, there was this idea that unattended ground sensors were going to trigger an RVSS camera to point in that direction, but the technology never seemed to work,” Dave Maass, Director of Investigations at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), an international nonprofit digital rights and research group, told The Markup.

“More recently, Anduril [a defense technology company] came in with ‘autonomous surveillance towers’ that were controlled by an AI system that would not only point the camera but also use computer vision to detect, identify, and track objects. All the other vendors have been trying to catch up with similar capabilities,” Maass added, referencing how the slide shows an unattended ground sensor going off and alerting a tower, then the tower AI does all the work of identifying, classifying and tracking the system, before handing it off to humans.

“To realize this increased level of autonomy throughout all surveillance and intelligence systems, USBP must leverage advances in AI, machine learning, and commercial sensors designed for an ever-evolving, autonomous world,” CBP said in a presentation, led by Julie Koo, the director of CBP’s industry partnership and outreach program.

But using AI and machine learning may come with ethical, legal, privacy, and human rights implications, experts say. Among the main concerns: the perpetuation of biases that may lead to discriminatory outcomes.

Eliza Aspen, a researcher on technology and inequality with Amnesty International, said advocates are “gravely concerned” about the proliferation of AI-enabled police and surveillance technologies at borders around the world, and its potential impact on borderland communities and asylum-seekers.

“These technologies are vulnerable to bias and errors, and may lead to the storage, collection, and use of information that threatens the right to privacy, non-discrimination, and other human rights,” Aspen said. “We’ve called on states to conduct human rights impact assessments and data impact assessments in the deployment of digital technologies at the border, including AI-enabled tools, as well as for states to address the risk that these tools may facilitate discrimination and other human rights violations against racial minorities, people living in poverty, and other marginalized populations.”

Hello World

A Virtual Reality Tour of Surveillance Tech at the Border

A conversation with Dave Maass of the Electronic Frontier Foundation

Mizue Aizeki, the executive director of The Surveillance Resistance Lab, said it’s important to digest the role that tech and AI is playing “in depriving rights and making it more difficult for people to access the very little rights that they have.

“One of the things that we’re very concerned about is how … the nature of the ability to give consent to give all this data is … almost meaningless because your ability to be seen as a person or to access any level of rights requires that you give up so much of your information,” she said.

“One of the things that becomes extremely difficult when you have these systems that are so obscured is how we can challenge them legally, especially in the context when people’s rights—the rights of people on the move and people migrating—become increasingly limited.”

Border Patrol had nearly 250,000 encounters with migrants crossing into the U.S. from Mexico in December 2023, the most recent month for which data is available. That was the highest monthly total on record, easily eclipsing the previous peak of about 224,000 encounters in May 2022.

Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, an associate policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, a research organization, called the growing tech arena “a double-edged sword.”

“On the one hand, advances in automation are really helpful for certain aspects of what happens at the southern border. I think it’s been extremely helpful, especially when migrants are stuck in perilous situations, if they’ve been hurt, if a member of their group is dehydrated or ill or something like that. There are different ways that, whether it’s via a cellphone or via some sort of remote tower or via something, Border Patrol has been able to do search and rescue missions,” she said.

“But there are still similar problems that Border Patrol has been facing for the last several years, like what happens after someone is apprehended and processed. That requires resources. It’s unclear if automation will provide that piece,” she said.

Though migration patterns have historically shifted as technology has advanced, Putzel-Kavanaugh said it’s too soon to tell if fully automated surveillance would scare migrants into taking on more dangerous journeys.

“I think that people have continued to migrate regardless of increased surveillance. AI could push people to take more perilous routes, or it could encourage people to just show up to one of the towers and say, ‘Hey, I’m here, come get me.’”

Samuel Chambers, a border researcher who’s been analyzing surveillance infrastructure and migration for years, said surveillance tech increases harm and has not made anything safer.

“My research has shown that the more surveillance there is, the riskier that the situation is to migrants,” Chambers said. “It is shown that it increases the amount of time, energy, and water used for a person to traverse the borderlands, so it increases the chances of things like hyperthermia, dehydration, exhaustion, kidney injuries, and ultimately death.”

During his State of the Union address this month, President Joe Biden touched on his administration’s plan to solve the border crisis: 5,800 new border and immigration security officers, a new $4.7 billion “Southwest Border Contingency Fund,” and more authority for the president’s office to shut down the border.

Maass of the EFF told The Markup he’s reviewed Industry Day documents going back decades. “It’s the same problems over and over and over again,” he said.

News

With AI, Anyone Can Be a Victim of Nonconsensual Porn. Can Laws Keep Up?

States around the country are scrambling to respond to the dramatic rise in deepfakes, a result of little regulation and easy-to-use apps

“History repeats every five to 10 years. You look at the newest version of Industry Day, and they’ve got fancier graphics in their presentation. But [the issues they describe are] the same issues they’ve been talking about for, gosh, like 30 years now,” Maass said. “For 30 years, they’ve been complaining about problems at the border—and for 30 years, surveillance has been touted as the answer. It’s been 30 years of nobody saying that it’s had any impact. Do they think that now these wonders could become a reality because of the rise of AI?”

In his 2025 budget unveiled earlier this month, Biden reiterated the unmet needs from an October request: the need to hire an additional 1,300 Border Patrol agents, 1,000 CBP officers, 1,600 asylum officers and support staffers, and 375 immigration judge teams.

Buried in that same budget was a $101.1 million surveillance upgrade request. In the brief, DHS told Congress the money would help maintain and repair its network of surveillance towers scattered throughout the borderlands. That’s in addition to the agency’s $6 billion “Integrated Surveillance Towers” initiative, which aims to increase the number of towers along the U.S.–Mexico border from an estimated 459 today to 1,000 by 2034.

The budget also includes $127 million for investments in border security “technology and assets between ports of entry,” and $86 million for air and marine operational support.