Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Hi everyone,

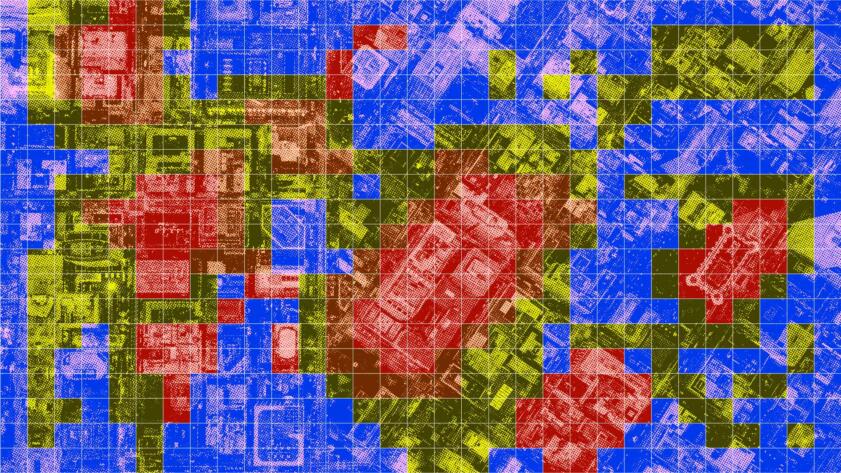

It’s Markup reporter Aaron Sankin again. In early October, I published an investigation into a predictive policing algorithm from a company called Geolitica, formerly known as PredPol. We compared the algorithm’s predictions on where and when crimes were most likely to occur to actual crime reports made to the police. Based on our analysis, those predictions were correct less than 1% of the time.

We got our crime report data from a police department in New Jersey that had purchased Geolitica’s algorithm. Police officials insisted that they bought the program thinking it would be helpful to prevent crime, but quickly realized it wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t already know.

Geolitica’s predictions weren’t effective, but the idea that crime tends to concentrate in particular areas, and in broadly predictable patterns, is supported by reams of criminology research. The company suggested sending police officers to these “hot spots” to prevent crimes through law enforcement presence alone.

What predictive policing doesn’t do is consider why these hot spots of reported crimes exist in the first place.

Prediction: Bias

Predictive Policing Software Terrible At Predicting Crimes

A software company sold a New Jersey police department an algorithm that was right less than 1% of the time

For a previous investigation into Geolitica’s algorithm, we asked 38 police departments what they asked officers to do when they arrived at a software-predicted location. No department mentioned asking officers to identify any factors that could have led to the prediction. Some said they suggested officers sit in their cars and fill out paperwork.

“If you want to solve a problem, if you want to understand a problem, you need to diagnose the problem,” Joel Caplan, a professor at the Rutgers School of Criminal Justice, told me. “Predictions are only proven right if you never fix the problem and the incidents keep happening when they’re predicted. That’s not prevention.”

Caplan was part of a research team at Rutgers that developed risk terrain modeling (RTM), which combines crime report data with land use information to help identify the reasons why crime might be clustering in a particular location. The focus isn’t solely on sending more cops to those locations—it’s about finding ways to think more clearly about the problem.

For example, “if you have five or six carjackings and you analyze them with RTM, you might realize that all of the carjackings are occurring at gas stations near highway on-ramps next to bus stops,” Caplan said. “And then you’re like, that makes sense because they’re using it to get away onto the highway. It’s not just all gas stations, it’s gas stations near highway on-ramps.”

When I showed a map of the predominantly low-income and Latino neighborhoods where Geolitica’s system had made predictions in Haverhill, Mass. to Bill Spirdione, the head of a food pantry in the city, he noted that it was largely a map of where people needed the most help from social services like his.

One place where RTM was used was in Newark, N.J., where the city employed the program to conduct a geographic analysis of aggravated assaults. The analysis identified a particular set of location types as the most frequent settings for assaults: parking lots, grocery stores, and abandoned properties. It was in the last category that the city took particularly interesting action.

The Rutgers team passed along the addresses of abandoned properties, including buildings and lots, where assaults were clustering to the city’s planning department, as well as some local community organizations, which used the data to help it decide which city-owned lots to purchase and turn into affordable housing.

“There might be five houses that they want to purchase and remediate, but they have limited resources so they have to choose which site is most suitable for their purchase and remediation,” Caplan said. “They used these results and said, if we’re going to remediate a house, and we can do it in a location that’s high-risk…They could help share the burden of crime prevention by doing what we’re already doing anyway.”

Other groups adapted city-owned vacant lots in high-risk locations into usable, public spaces with amenities like playgrounds. In her seminal work, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” Jane Jacobs wrote about the concept of “eyes on street,” which holds that crime is more likely to occur in spaces where there aren’t observers. Turning a vacant lot into an inviting public space would make that area safer simply by increasing the number of people there at any given time.

Caplan was unable to point to any figures showing how these property remediation programs affected crime rates. However, he highlighted another program in Newark, where RTM was used to identify areas with the highest risk of car thefts. Those parts of the city were targeted for the distribution of flyers reminding people not to leave their unlocked cars unattended, resulting in a nearly 50 percent decrease in auto theft.

Geolitica, which is shutting down operations at the end of this year, and SoundThinking, the company acquiring many of its assets, have both indicated they’ve incorporated elements of RTM into their own patrol management platforms. It’s a sign that, at least in this particular law enforcement context, there is (hopefully) a growing realization that predictive analytics shouldn’t be a shortcut around having to do the hard thinking about why a problem exists in the first place.

Thanks for reading,

Aaron Sankin

Investigative Reporter,

The Markup