Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Hello,

My name is Maddy Varner, and I’m an investigative data journalist here at The Markup. When I’m not crunching numbers and cleaning pdfs for our stories, one of the things I enjoy doing in my spare time is natural dyeing. Dunking fabric into buckets filled with weird extracts and dried flowers might seem like the farthest thing from data journalism—but the two practices have similarities.

Much like data journalists, dyers are obsessed with reproducibility. This is for practical reasons: If you’re able to attain a color you really like, you want to know how to do it again. Dyers carefully monitor factors like temperature, pH levels, weights of both the fabric and dye material, and what sort of preprocessing, or “mordanting,” is done before a fabric is thrown into a dye bath. All of this is meticulously recorded in a dyer’s journal, along with an actual sample of the resulting fabric.

Some readers might be reminded of what journalist and Arizona State University professor Sarah Cohen calls a data diary. Reporters at places like the Associated Press, the Center for Public Integrity, and here at The Markup will spend time recording what kinds of analyses they tried, what worked (and what didn’t!), and what questions they still have about a dataset.

Often, a large part of dyeing is actually going out into the world and gathering materials, in the same way a data journalist must go out and collect information or build bespoke datasets to understand a topic. Projects like Julia Beeler’s Mushroom Color Atlas, which documents hundreds of colors produced by dyeing with different fungi, “show their work” (much like our methodology series here at The Markup) by including detailed notes about how each sample was collected and processed.

Much like data journalists, dyers are obsessed with reproducibility.

While journalists’ diligent data collection and careful documentation of their work will build up to a finished analysis, a dyer’s goal is typically a specific color.

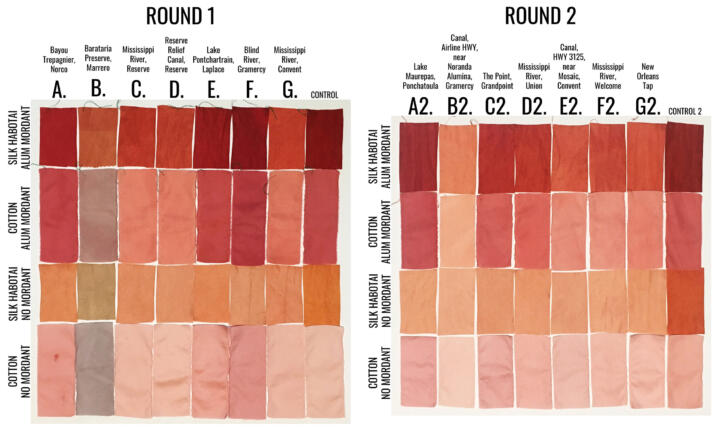

That’s why when I saw artist Jamie Bourgeois’s project Water Madders, I was struck by the way she was instead using color as a signal to help her understand Gulf Coast water pollution. Bourgeois tested how madder root—known for centuries by dyers for both its bright red color and sensitivity to the water it’s used with—reacted to different samples she collected from waterways near her hometown.

Bourgeois grew up in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, an area along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge that has a high density of industrial plants and some of the highest rates of cancer in the United States. When she started her project, local activists, including the groups Rise St. James and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, were fighting to stop an affiliate of Formosa Plastics from building a petrochemical plant in the area. A Louisiana judge has since revoked the plant’s air permits, and residents recently sued St. James Parish, calling for a moratorium on the construction of similar plants.

The results of Bourgeois’s initial tests showed variations in shades across different samples, and while she’s still performing control experiments to understand what might have caused these differences, she plans to continue to try to make invisible things affecting her hometown’s waterways visible. Conversations with environmental scientists, activists, and other dyers have helped shape the hypotheses she’ll test in the future.

I had the opportunity to speak with Bourgeois about her project, what she learned, and how others can use creative approaches to ask questions about the world around them.

Our conversation is edited for brevity and clarity.

Varner: Tell me a bit about yourself. What led you to work on Water Madders?

Bourgeois: I’m originally from St. James Parish, La. I was very interested in art when I was in high school, and all of my family did lots of hunting and outdoor recreational activities. But this idea of the environment and the impact of all of the petrochemical plants was not very present, or really a thought in my mind, until I went to college and I ended up taking an environmental science class. And somehow for one of the projects—I don’t know if it was to research something in your hometown or what—I landed on an article that talked about Louisiana’s Cancer Alley and discovered that my hometown was smack in the middle.

That was my first introduction to the environmental problems in my hometown. Of course, I had always heard of the different advisories for Blind River, which is a river that I swam in, ate food from, and that sort of thing as a young child, but it wasn’t a red flag. Even though there were advisories of mercury poisoning in the river, nobody really paid much attention to it.

Fast-forward a number of years. When I graduated, I decided my studio practice was going to focus around natural dyes. And so I did lots of different research, read books, contacted different artists and artisans, and learned just lots of different techniques and properties of natural dyeing. My work started to focus on Louisiana, and all my ideas were very illustration-based, using natural dyes to create the color and the actual line work in the screen printed textiles that I was creating.

Then there was news that this fertilizer plant in Convent, La., which is in St. James Parish, had a breach in their waste stacks. There was all this news circulating about the fact that if this thing busts, it’s going to send all of this sulfuric acid and radioactive material into the nearby waterways, and I believe that’s when I started thinking about this idea of pollution in the water.

Water is not just water.

Acidity affects the natural dyes, but so do different metals, salts—all this stuff really affects what your color outcome is. And so I started thinking about that, and how I could do these tests and incorporate natural dyes into maybe visually being able to see if certain bodies of water are polluted or not.

Varner: When people talk about natural dyeing, color is often framed as the goal and not a signal. Can you talk a bit about why you wanted to use color as a signal in this project, and some of the challenges you ran into with that?

Bourgeois: Even with natural dyes, for the most part, people don’t think about their water quality. They don’t understand that the invisible things in the water can affect the outcome of the color. You know, it’s just like, “Oh, madder is red, so I’m gonna get a red textile.” But there are so many more steps in dyeing a piece of fabric with a plant dye, or an insect dye. It’s not as easy as just putting some plants in a pot and turning the water heat up.

The goal of using color was to be able to visually demonstrate that not all water is the same. I was hoping to see if I could sort of pull out the pollution, but then what I figured out was that it’s very complex. It’s very possible that I’m demonstrating pollution, but I think I need to gather and do way more tests in order to prove something.

It started out as me wanting to prove something and became more of an educational tool to have people visualize and immediately see that water is not just water.

Varner: Can you tell me about your water collection process? Did you run into any issues or surprises while collecting samples?

Bourgeois: I knew I wanted to get multiple sites on the Mississippi River. I didn’t have access to a boat to go into the middle of the rivers, just the shorelines. So all of the places were just places where I can get access to, and I wanted to get different parts of the river, but then also the Blind River and then the man-made canals. And then I got a sample close to where Mosaic [the Convent fertilizer plant] had the breach and those types of things.

While I was starting this project, it was also the beginning of media coverage of Formosa Plastics, which Rise St. James and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade were fighting against. So I went to their proposed site. I went to the Mississippi River, and I went over the levee, and I went down to the water to collect there. If the plant was successfully built, I was hoping to go back year after year to keep collecting samples to see how the water changed.

There was a security guard in a golf cart that was sort of like guarding the site. And he did question me, but I just sort of played the, “Oh, I’m just an artist doing an art project!” And he was like, “O.K.” So I was able to go and collect water.

Varner: As part of your project, you mentioned that you started having conversations with environmental scientists, among other groups. How did those conversations shape or change your project?

Talking to these different scientists and professionals really enriched the entire process….

Bourgeois: Talking to these different scientists and professionals really enriched the entire process and gave me even more questions and even more ideas on what I could do next. I have all these different plans and ideas for continuing this project; I just haven’t had a chance to get out there yet. I want to test in different ways and be a little bit more methodical about how I’m testing and where I’m testing, and getting better tools to do sort of the control tests.

The more knowledge I gather from scientists and professionals, the more tools I have to think about what the results are. I mean, that’s how science is right? You have the hypothesis and you test.

And then also talking to other natural dyers as well. I have some great friends that are more knowledgeable in the chemistry of natural dyes that have really helped me to sort of think differently about the results that I got.

This project, in general, connected me with people that I wouldn’t have contacted otherwise, or maybe just would have known them from behind the screen but never actually interacted with, but now it gives me an opportunity to connect and learn more from these people directly.

Varner: Do you have any advice for others who want to learn more about their communities and environments?

Bourgeois: If you have questions, or if there’s something you want to learn more about, don’t be afraid to reach out. It’s always daunting and intimidating to reach out to people who you admire, but it’s so worth it. And usually those people love that you’re reaching out and want to talk to you. If you have a question about a water body, or trees, or invasive species, or if you just want to know more about the land’s history, just start doing research and finding the people who might have the knowledge and ask them questions, and more questions will pop up. And that’s how the ball gets rolling—by being curious and then pursuing the curiosities.

Thanks for reading.

All the best,

Maddy Varner

Investigative Data Journalist

The Markup