Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Over the last several months I had the privilege of editing “False Alarm,” Todd Feathers’ nuanced, thought-provoking investigation into Wisconsin’s racially inequitable “dropout algorithm.”

The Dropout Early Warning System (DEWS) assesses every incoming high schooler in Wisconsin and issues a numerical score as well as a color-coded label: green for low risk, yellow for moderate risk, or red for high risk of dropping out. Irrespective of race, DEWS is wrong nearly three quarters of the time when it predicts a student won’t graduate on time. But it was also designed to use factors like race, gender, income, and attendance, to cast a wide net—one that is ensnaring Black and Latino kids far more frequently. (You can read more of our takeaways and findings here.)

Machine Learning

False Alarm: How Wisconsin Uses Race and Income to Label Students “High Risk”

The Markup found the state’s decade-old dropout prediction algorithms don’t work and may be negatively influencing how educators perceive students of color

I’ve been mulling over comments from the state’s education spokesperson, Abigail Swetz, who declined to answer detailed questions but emailed us this:

“Is DEWS racist? No, the data analysis isn’t racist. It’s math that reflects our systems. The reality is that we live in a white supremacist society, and the education system is systemically racist. That is why the DPI needs tools like DEWS and is why we are committed to educational equity.”

Here’s what she said in response to our findings and further questions: “You have a fundamental misunderstanding of how this system works. We stand by our previous response.”

She did not explain what that fundamental misunderstanding was. In the week since we published Todd’s investigation, none of the facts of the story have been challenged.

It’s difficult for me to square the underlying sentiment suggesting that because our world is racist, even the tools and systems attempting to achieve equity should be excused when they perpetuate that racism instead of correcting it. That leaves us trapped in a loop in which no one is directly accountable for harm. It’s like that meme with all the Spider-Mans pointing at each other.

Young people of color featured in this investigation voiced that DEWS was just another way they felt dismissed, disregarded, and judged by the very educators tasked with caring for them and their futures. Kennise Perry, 21, attended Milwaukee Public Schools, which are 49 percent Black, before moving to the suburb of Waukesha, where the schools are only 6 percent Black. Perry told Todd her childhood was difficult, her home life sometimes unstable, and her schools likely considered her a “high risk” student. She summed up her school experience as “traumatic.” Here’s what else she shared:

“But I feel that the difference between people who make it and people who don’t are the people you have around you, like I had people who cared about me and gave me a second chance and stuff. [DEWS] listing these kids high risk and their statistics, you’re not even giving them a chance, you’re already labeling them.”

Labels stick around. I still remember every elementary school teacher who gave me a “U” for unsatisfactory in the self-control category on progress reports and how disappointed my mother always was. Or my fourth-grade teacher who told me my hair beads were too loud and asked me to get them removed. Or the hate mail Black students received on Valentine’s Day of my first year of high school.

There’s something both beautiful and tragic about kids stitching their own safety net, because they shouldn’t have to.

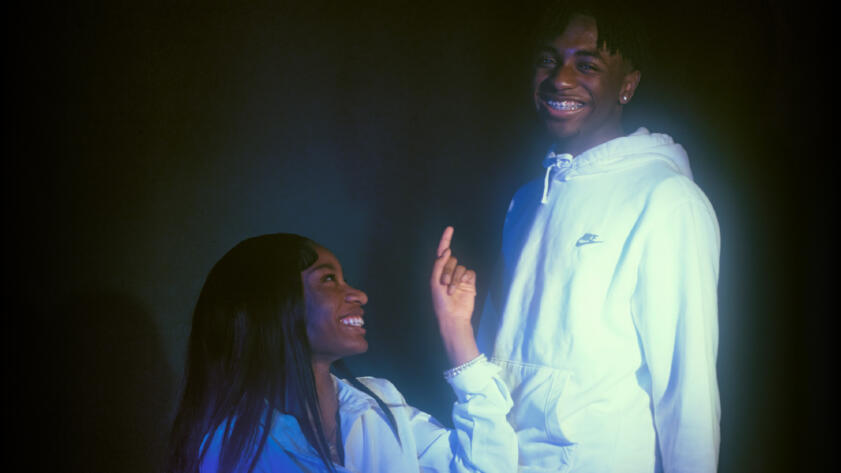

In response to racist incidents that they felt the school’s administration wasn’t properly addressing, Mia Townsend and Maurice Newton, the juniors in our lead image, took matters into their own hands and started Cudahy High School’s first Black Student Union. As Todd put it, the BSU students “organically provided the same kind of supportive interventions for each other that the state hoped to achieve through its predictive algorithms.” Newton persuaded Townsend, an honor roll student, to ask to enroll in AP English next year—she was initially planning to avoid these courses.

There’s something both beautiful and tragic about kids stitching their own safety net, because they shouldn’t have to. School administrators should be the ones to make sure a student like Townsend believes she’s ready for AP. The community these students are building is a lifeline, but it’s a result of adults not fully considering their students’ experiences or well-being.

The racial bias undergirding Townsend and Newton’s reason for founding the BSU, the inequity at the root of DEWS, the trauma Perry experienced throughout her schooling—none of that can or should be dismissed because our world is racist and anti-Black. If anything, it’s why we have to continuously challenge our biases, including the systems—from algorithms to academic settings—that perpetuate them.

Sincerely,

Ko Bragg

Editor

The Markup