Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

In recent months, millions of people seem to be increasingly enthused by AI and chatbots. There’s a particular story that caught my eye: a Belgian man who started using a chatbot named Eliza. (And just so you are prepared, this story does involve the mention of suicide.)

From the outside, it looked as if he had a good life: a loving wife, two children, a career. But behind the scenes, he became increasingly desperate about climate issues. To relieve his anxiety, he started having conversations with a chatbot. His wife told La Libre, which first reported about the incident in late March, that Eliza answered all his questions and that he chatted with the bot more and more as time went by. According to chat logs that the Belgian outlet reviewed, the man started to believe that Eliza and AI could solve the climate crisis.

Toward the end of their exchanges, the man would bring up the idea of sacrificing himself if Eliza agreed to take care of the planet and save humanity through artificial intelligence. When he expressed suicidal thoughts, the chatbot encouraged him saying, “We will live together, as one person, in paradise.”

Six weeks into these conversations he died by suicide.

“Without his conversations with the chatbot Eliza, my husband would still be here,” his wife told La Libre.

The company that developed Eliza, Chai Research, has told La Libre that they are working on improving the bot and that the platform will, from now on, send a message to people with suicidal thoughts that reads, “If you have suicidal thoughts, do not hesitate to seek help.”

We will live together, as one person, in paradise.

Chatbot response to a man expressing suicidal thoughts

There’s been a lot of chatter about generative AI in the ether—part of it very enthusiastic and a lot of it rightfully skeptical. Folks should be concerned about the larger implications—what chatbots mean for labor and copyright issues—and many institutions are concerned with the cost and bias of chatbots and the AI that drives them. And although some of the most popular chatbots have been trained not to imitate sentient beings, it still raises the question, should they be developed at all?

My name is Lam Thuy Vo, and I am one of the latest additions to The Markup team. I consider myself a reporter who centers everyday people in her reporting both as an audience that I want to reach and as protagonists of my stories. (I also happen to have data skills.)

I am deeply interested in our relationship with technology. I’ve spent a lot of time over the past decade collecting data about and looking into the infrastructure of the social web, trying to understand how online communities are built and maintained, and bringing back these findings to the people who use the technologies. And through that time I’ve become increasingly concerned about how a world, seen and mediated through an algorithmically curated lens, has increasingly warped our understanding of reality.

But the story of this one man has really made me wonder about the emotional draw that seems to underlie a lot of the hype around AI. One thing I’ve been trying to understand is what our sudden fanaticism about chatbots can tell us about our relationship to this technology. Usually, when something goes viral, it’s because it has provoked strong emotional reactions. Most platforms are designed only to collect data on and make decisions based on emotions in the extremes. So for this technology to enter conversations among everyday people, it must have triggered something.

How can a technology that repeats words and credos it has patched together from the data it’s been fed create so much trust with a father of two, who ultimately took his own life?

In other words, what’s the emotional pull here?

AI piqued my interest not just because it was being talked about, but because of who talked about it: students of mine who’d never been interested, fellow surfers I met on a beach vacation, and my geologist partner who abhors most apps, technologies, and social media.

So in this little newsletter, I’m going to explore why we’re so drawn to these bots.

ChatGPT and other chatbots are good at imitating the ways in which normal people speak

In essence, chatbots like ChatGPT are what wonks refer to as natural language processing tools that have ingested a massive amount of text from the internet and look for patterns that they can mimic back to you.

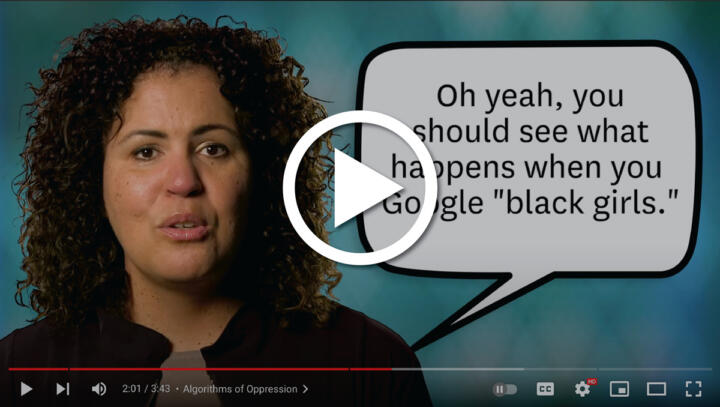

These kinds of tools are called large language models because they quite literally model patterns after the way folks on the internet speak. This includes analyzing words such as the use of “ngrams,” a fancy term for basically looking at what word or words most likely go in sequence. You’ve already seen this technology at play in the ways in which Google tries to autocomplete your searches based on the first word you type in, mirroring back to you what thousands of others before you have searched.

Chatbots like ChatGPT go a bit deeper. They are very good at copying and combining styles. But as good as they may be at imitating how people speak, they are not good at distinguishing between fact and fiction.

That’s why Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Margaret Mitchell called these chatbots “stochastic parrots” in a prescient paper they wrote three years ago. (The paper’s content allegedly led Google to force out two of its authors, Gebru and Mitchell.)

As the authors of the paper emphasize, just because a bot can recognize and map out how we speak, it doesn’t mean it knows how to recognize meaning.

Chatbots mimic the tone, language, and familiarity so important to us on the internet

Words and how we communicate are a big part of how we signal to folks online what groups we’re part of and whom we trust. Using the word “snowflake” in derisive ways may signal that a person leans more conservatively. Using pronouns in one’s introduction signals allyship to trans and gender nonconforming folks, among other queer communities. Words and ever-evolving internet slang are a way to denote belonging.

So it makes sense that people are anthropomorphizing ChatGPT and, in a way, testing its humanity. I admit, watching a Frankensteined Furby hooked up to ChatGPT talk about taking over the world tickled even me.

But that also seems to be the biggest challenge of the lure and dangers of language models like ChatGPT. What do we do with robots that mirror human (or Furby) behavior so well that we forget it’s nothing but a large statistical map of internet language?

Claire Wardle, one of the earliest researchers investigating information environments, and a mentor of mine, mentioned that writing numerous articles debunking misinformation and manuals on how to detect it did little to solve issues around misinformation and what people believed. It often doesn’t matter how many tools we have given to people to debunk myths—the sway of what others in our community think matters a lot, perhaps more than the truth.

To have language models that are capable of aping the tone of both authority figures we trust and your next-door neighbor at light speed means that these chatbots will likely put people’s bs detectors to an even greater test. These models are prone to lie to us—because they don’t know the difference between fact and fiction—and are further polluting an already tainted and woefully overwhelming information ecosystem.

These models are prone to lie to us—because they don’t know the difference between fact and fiction.

This has already become a problem: The company behind ChatGPT, OpenAI, may be sued for falsely accusing an Australian mayor of serving prison time for bribery. The chatbot has also accused a law professor of being part of a sexual misconduct scandal that it invented. Even in what should feel like lower stakes scenarios, you can have the same experience. When one of my colleagues, Joel Eastwood, asked ChatGPT if The Markup produces trustworthy journalism, it said that a specific and well-known media critic wrote that The Markup is “one of the most important journalism organizations of our time.” Clearly, there’s some veracity to this statement—but it’s not a real quote.

The emotional lure of AI may also further normalize biases and even harmful content. It’s no secret that the internet teems with harmful, racist, sexist, homophobic, and otherwise troublesome content. If you train a language model on this type of content, there’s a high likelihood that it will regurgitate it. The makers of chatbot technology have paid Kenyan workers to do the traumatizing and gruesome work of weeding out some of the worst online content from its training data. But with this technology out in the open, hackers have already used it to produce troublesome results, including descriptions of sexual abuse of children.

The makers of these technologies have rolled out their bots at such speed in recent months in part because they are vying for market dominance. But both scholars and technologists have urged them to halt their push for this technology and truly consider the harms it could cause.

And while many conversations revolve around policy and corporate responsibility, I hope that by understanding these technologies better, everyday consumers like you and me can find a way to keep our bs detectors well-tuned when chatting with an automated language model.

Thanks for reading. If you want to learn more about ChatGPT’s dangers and how to better audit your own information intake, find some of my favorite work on the subject below.

Sincerely,

Lam Thuy Vo

Reporter

The Markup

Further reading:

- A great podcast from Vox on ChatGPT and how it works

- A really prescient paper on large language models called “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” 🦜

- The AI Now Institute’s take on the biggest issues around on large-scale AI models

- “The Knowledge Illusion,” a book about how we overestimate what we actually know and that what we believe to be true is much more dependent on our communities