Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Hi, folks, my name is Todd Feathers, and I’m an enterprise reporter here at The Markup.

Last month, reporters at Lighthouse Reports and Wired published “Inside the Suspicion Machine,” a tremendous exposé of the fraud-detection algorithm used by the city of Rotterdam, Netherlands, to deny tens of thousands of people welfare benefits.

The investigation showed that the algorithm, built for Rotterdam by the consultancy Accenture, discriminated on the basis of ethnicity and gender. And most impressively, it demonstrated in exacting detail how and why the algorithm behaved the way it did. (Congrats to the Lighthouse/Wired team, including Dhruv Mehrotra, who readers may recall helped us investigate crime prediction algorithms in 2021.)

Cities around the world and quite a few U.S. states are using similar algorithms built by private companies to flag citizens for benefits fraud. Not for lack of trying, we know very little about how they work. Lighthouse and Wired were able to demonstrate how much a single input variable, such as being a parent, affected a Rotterdam applicant’s risk score. But in many places, we don’t even know what the input variables are for these high-stakes decision-making systems.

How a fraud detection algorithm makes its calculations and why it was designed to operate that way aren’t merely questions of interest to journalists. People automatically denied benefits need that basic information to appeal decisions when their right to due process has been violated.

“A lot of the time there’s an overall cost-cutting happening [by welfare agencies], and an algorithmic determination is used to paper over the real reason benefits are being reduced and to offer a seemingly neutral reduction, but in order to challenge it, you need to be able to pinpoint the reason. Without that information, you can’t mount a challenge,” said Hannah Bloch-Wehba, a Texas A&M School of Law professor who studies how algorithmic opacity threatens fair government. “That’s what we are owed as citizens of the state: that, when it takes away something to which we are entitled, at the very least, they should tell us why.”

When [the state] takes away something to which we are entitled, at the very least, they should tell us why.

Hannah Block-Wehba, Texas A&M School of Law

People denied food and rent benefits or placed under investigation because of Rotterdam’s algorithm can now begin to understand how the system failed only because Lighthouse did something epically, mythically difficult: It obtained what it described as the “holy trinity of algorithmic accountability: the training data, the model file and the code.”

“It took nearly two years to acquire the materials necessary to carry out this experiment,” the reporters wrote in their methodology. “We sent FOIAs (Freedom of Information requests) to governments across Europe requesting documentation, evaluations, code, and training data for machine learning models similar to the one deployed by Rotterdam.”

Rotterdam was the only city to provide the model file and other technical documentation, and that was after a year of negotiations. In the end, it still took a stroke of luck for the reporters to get the training data: City officials unknowingly included it in the source code of histograms they sent to reporters.

It took six years, from the algorithm’s deployment in 2017 until “Inside the Suspicion Machine” published, for the public to get a full picture of how it worked and what went wrong. Rotterdam stopped using the algorithm in 2021.

Unfortunately, we never get close to obtaining the “holy trinity” for most government decision-making algorithms. And the more cities and states turn to government by private algorithm, the less effective the tools of transparency used by journalists, activists, and people harmed by algorithms seem to become.

It’s been 10 years since the state of Michigan launched the Michigan Integrated Data Automation System (MiDAS), a fraud-detection algorithm with a 93 percent error rate that automatically denied tens of thousands of qualified applicants their unemployment benefits, leading to bankruptcies and home foreclosures.

Lawyers fighting on the front line against MiDAS’s determinations still don’t have full clarity into how the system—which remains in operation after some reforms—was designed and operates. What information they do have has largely been gleaned through state and federal lawsuits brought by Michiganders who had their tax returns garnished after MiDAS automatically flagged them for misrepresentations and initiated collections on their accounts.

It took nearly two years to acquire the materials necessary to carry out this experiment.

Lighthouse Reports and Wired

“I still don’t know if we’ve actually seen the formal algorithm,” said Tony Paris, an attorney with the nonprofit Sugar Law Center for Economic and Social Justice who has represented unemployment applicants caught up in MiDAS’s mistakes.

Bloch-Wehba has said that, when algorithms are used to deprive citizens of liberty or property, governments should be required to disclose input variables and how they are weighed. Several states are considering bills that would require agencies to document the automated decision systems they use and perform algorithmic impact assessments.

But across the country, lawmakers’ prior efforts to mandate greater transparency for government automated decision systems have largely sputtered out. In 2021, more than 30 Michigan legislators co-sponsored a bill that would have mandated the state hire an independent expert to audit MiDAS’s source code and algorithms. The bill didn’t make it out of committee.

Meanwhile, FAST Enterprises, one of the companies primarily responsible for MiDAS, says in promotional material that six other states use its unemployment benefits software: Massachusetts, Montana, Oregon, Nevada, Tennessee, and Washington, which has had its own problems with the company. It’s not clear whether all those states’ systems include algorithmic fraud detection.

And FAST isn’t the only vendor of these systems. For several years, the nonprofit Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) has been tracking the spread of technologies from Pondera Solutions, which sells its “Fraudcaster” algorithm to cities and states. Thomson Reuters acquired Pondera in 2020.

Like the reporters at Lighthouse, those covering MiDAS in Michigan, and many of us here at The Markup, EPIC’s staff has primarily used public records requests to try to pull back the curtain on government algorithms. Every U.S. state and many national governments (including the U.S.’s) have a freedom of information or open records law that allows the public to request documentation of government business. It’s an amazing system and the backbone of a lot of investigative journalism. But when it comes to getting information about algorithms that governments have hired private companies to build, freedom of information laws are falling short. Lighthouse’s success is a notable exception, and it took a long time.

EPIC’s Ben Winters and Tom McBrien said that many government agencies they made information requests to about Pondera simply never responded (which is illegal). Some agencies that did respond gave EPIC copies of their contracts with Pondera, which listed specific deliverables like validation tests of the fraud-detection system. But when EPIC subsequently requested the results of those tests, the agencies “stonewalled or there was pushback to say that’s proprietary or confidential” information, McBrien said.

In my own reporting, I’m regularly turned away by agencies claiming trade secret exemptions.

Despite their extensive public records work, EPIC, and by extension the rest of us, still don’t know all the input variables that cities and states feed into Pondera’s Fraudcaster system. We don’t know how exactly Fraudcaster calculates risk or what decisions humans made about how those predictions should be used.

Winters and McBrien didn’t even ask agencies for Pondera’s code or training data—pillars of that holy trinity of algorithmic fairness—and I don’t either in most cases. At least in the U.S., government agencies and public records appeals bodies have held that the most detailed but vital information about privately built algorithms are shielded from public view, even when those algorithms were created for the sole purpose of performing a core government function.

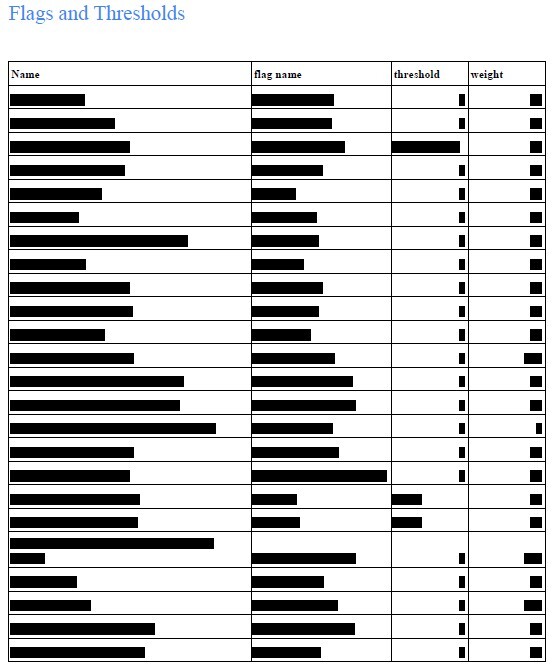

In all honesty, this column has been a 1,500-word subtweet about several government agencies and benefits-fraud-detection companies that—at least for the time being—will remain nameless. Suffice it to say, I’ve been trying to learn more about a particular algorithm used to detect fraud in several government benefits programs—and not getting nearly as far as I’d like. Sometimes you get the holy trinity, sometimes you get pages of this:

But this topic has implications that go well beyond my own challenges as a reporter. This particular kind of public-private partnership and the opacity and stonewalling it creates threatens the due process rights of tens of thousands of people.

There isn’t going to be a journalistic exposé for every fraud-detection algorithm out there. And even if there were, the information isn’t getting to the people who need it fast enough.

As Bloch-Wehba told me, “The big question is not ultimately ‘How do we know what’s happening.’ It’s ‘How do we know it before it’s too late.’ ”

Thanks for reading,

Todd Feathers

Enterprise Reporter

The Markup