Since we launched Blacklight, our real-time website privacy inspector, The Markup readers have used it to scan hundreds of thousands of websites to find out which user-tracking technologies appear on them.

Based on the questions we’ve been getting, it seems that one result in particular is causing users a bit of consternation.

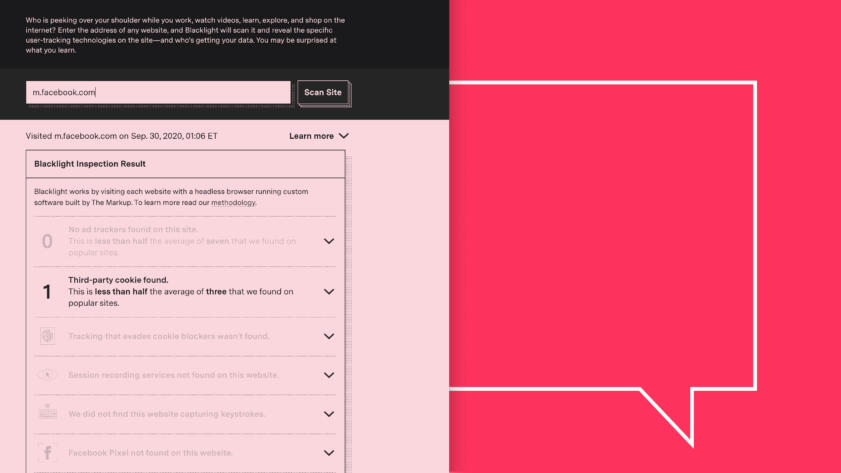

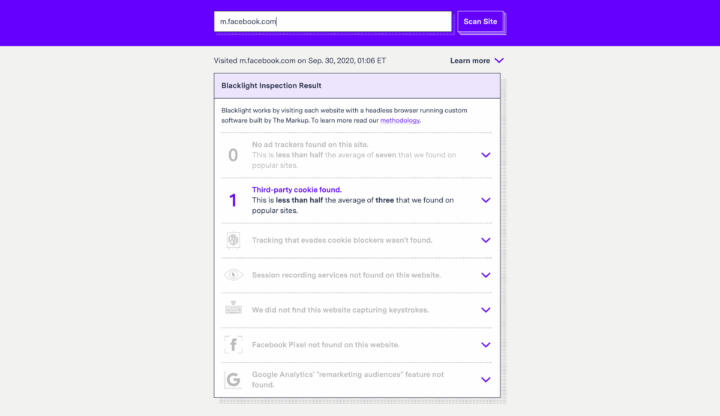

Scanning Facebook.com with Blacklight returns a clean bill of health, save for a single third-party cookie set by Google’s advertising arm, DoubleClick. (A third-party cookie is a string of data that a website installs on your device that allows the installer to recognize you on other websites where it has also installed tracking technology.)

Facebook is infamous for obsessively tracking people—is Blacklight saying it doesn’t track people on its own website?

That is decidedly not what we’re saying.

Two things are at play. One, Blacklight tests for third-party cookies—trackers that send data to others, not the website you are currently scanning.

And, two, Blacklight can’t sign on to your Facebook account (or your Instagram account or your Amazon account or your Netflix account or … you get the picture). When you ask Blacklight to scan sites that require a sign-in to access information, it can only run tests for tracking technology on pages that are outside that wall, such as the sign-in page itself.

If you think of Facebook like a store that sells chairs, Blacklight just takes you for a spin around the parking lot to check whether anyone is sitting in a parked car jotting down the license plate numbers of everyone who comes through. While that parking lot may appear to be relatively free of creeps, that’s not to say there isn’t someone inside jotting down credit card numbers at the checkout.

We found that Facebook, for its part, has placed its own tracking technologies on a third of popular websites around the world. But, when it comes to its own website, Facebook only allows the aforementioned single third-party (external) cookie.

By the way, for Blacklight users who noticed that the tool scanned Facebook’s mobile page and wondered why, Blacklight emulates an iPhone largely as a way to avoid bot-detection tools. But that doesn’t affect the outcome: The third-party tracking is similar on Facebook’s pages both on desktop and mobile (which was also true of other social media sites we checked).

So how do I know when and how Facebook is watching me when I use its site?

We got a clue of Facebook’s first-party tracking technologies when we looked at the code that appeared on Facebook’s log-in page in late September. The site attempted to set seven different cookies. (Again, these first-party trackers aren’t reported in Blacklight results.)

One of those cookies is the “fr” cookie, which, according to the company’s cookie policy, is “Facebook’s primary advertising cookie” and contains information like your Facebook user ID. It allows the company to link someone’s browsing history across the web with his or her Facebook profile.

Another is the “datr” cookie. Facebook’s cookie policy says that this cookie, “Identifies browsers for purposes of security and site integrity, including for account recovery, and identification of potentially compromised accounts.” The cookie has been controversial nonetheless. The Belgian Privacy Commission tried to stop Facebook from placing it on users’ devices in 2015, claiming it was being used to track people for advertising purposes. The dispute is ongoing.

Once you’re fully logged into Facebook, the platform sets first-party cookies on its internal pages, which The Markup was able to see by inspecting network requests appearing on a logged-in Facebook account in a standard web browser. The company tracks users’ actions in myriad ways. For example, its data policy discloses that Facebook collects “information about the people, Pages, accounts, hashtags and groups you are connected to and how you interact with them.”

This internal tracking can be used for a number of reasons—for example, Facebook’s “wd” cookie is used to remember the dimensions of a user’s browser window to make pages load more efficiently, according to CookieDatabase.org. But the main reason Facebook follows you around its site is to build detailed profiles of each user’s interests in order to target ads that presumably will be more successful than non-personalized ads, since they’re in some way connected to things the user sought out on his or her own.

(Pro tip: you can click here to check out what Facebook thinks your interests are. Some of its guesses will be based on your web browsing outside the Facebook garden because of the cookies the company has set on other sites.)

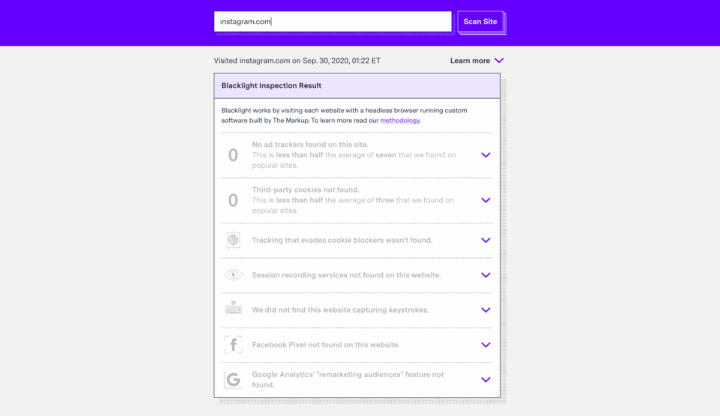

Is it the same deal with Instagram? Lots of first-party trackers but few third-party trackers?

It is, in fact, the same deal. Facebook owns Instagram.

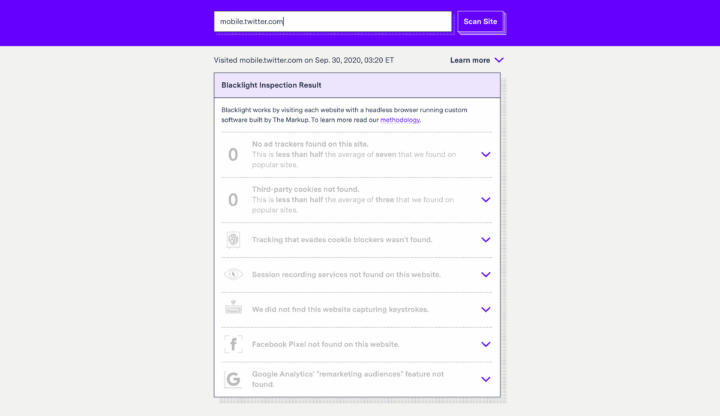

And in case you were wondering, Twitter’s landing page is also clean, at least when it comes to third-party tracking.

Why would Facebook want to use first-party tracking instead of third-party tracking?

Facebook spokesperson Alex Dziedzan didn’t answer specific questions about this but rather directed The Markup to the company’s browser cookies page (which can be found by going to Facebook’s cookie policy and then clicking on the “cookies” hyperlink in the first paragraph of the “Why do we use cookies” section).

Speaking very broadly, third-party tracking has a stronger association with online advertising than does first-party tracking. First-party tracking is how sites perform important and relatively innocuous tasks like remembering you so you don’t have to sign in again every time you visit a page.

As a result, privacy-protecting web browsers have taken steps to curtail third-party tracking while mostly permitting first-party tracking. All of the major browsers, except for Google’s Chrome, block third-party cookies by default, and Google has promised Chrome will soon follow suit. If a website wants to track users, it’s going to be easier for them to do it using first-party cookies than third-party ones.

That’s why, a couple of years ago, Facebook introduced a first-party cookie that other website operators can place on their pages that looks, to web browsers, like a first-party tracker but still sends data to Facebook.

“The cookie looks like it’s coming from the site displaying the ad, while in fact it sends data back to Facebook and, as such, performs functions typical of third-party cookies,” explained a blog post by the advertising technology company ClearCode.

“Abandoning the ‘legacy’ third-party cookie and switching to the first-party cookie as the default option for the Facebook Pixel”—a tracker that works in conjunction with the company’s third-party cookies—the blog post said, “is intended to help businesses continue using analytics and tracking ad attribution, independently of the browser they’re using.”

How do I make sure Facebook doesn’t track me as I move across the web?

One way to prevent Facebook from linking what you do on its platform with all the other stuff you do while browsing the web is to use Facebook Container extension for Mozilla’s Firefox browser. This extension effectively walls off what you do on Facebook from everything else you do on the internet, thereby limiting the company’s view into your online behavior.

How do I make sure Facebook doesn’t track me on Facebook?

Delete your account.