Hello, friends,

I first learned the term “risk assessments” in 2014 when I read a short paper called “Data & Civil Rights: A Criminal Justice Primer,” written by researchers at Data & Society. I was shocked to learn that software was being used throughout the criminal justice system to predict whether defendants were likely to commit future crimes. It sounded like science fiction.

I didn’t know much about criminal justice at the time, but as a longtime technology reporter, I knew that algorithms for predicting human behavior didn’t seem ready for prime time. After all, Google’s ad targeting algorithm thought I was a man, and most of the ads that followed me around the web were for things I had already bought.

So I decided I should test a criminal justice risk assessment algorithm to see if it was accurate. Two years and a lot of hard work later, my team at ProPublica published “Machine Bias,” an investigation proving that a popular criminal risk assessment tool was biased against Black defendants, possibly leading them to be unfairly kept longer in pretrial detention.

Specifically what we found—and detailed in an extensive methodology—was that the risk scores were not particularly accurate (60 percent) at predicting future arrests and that when they were wrong, they were twice as likely to incorrectly predict Black that defendants would be arrested in the future compared with White defendants.

In other words, the algorithm overestimated the likelihood that Black defendants would later be arrested and underestimated the likelihood that White defendants would later be arrested.

But despite those well-known flaws, risk assessment algorithms are still popular in the criminal justice system, where judges use them to help decide everything from whether to grant pretrial release to the length of prison sentences.

And the idea of using software to predict the risk of human behaviors is catching on in other sectors as well. Risk assessments are being used by police to identify future criminals and by social service agencies to predict which children might be abused.

Last year, The Markup investigative reporter Lauren Kirchner and Matthew Goldstein of The New York Times investigated the tenant screening algorithms that landlords use to predict which applicants are likely to be good tenants. They found that the algorithms use sloppy matching techniques that often generate incorrect reports, falsely labeling people as having criminal or eviction records. The problem is particularly acute among minority groups, which tend to have fewer unique last names. For example, more than 12 million Latinos nationwide share just 26 surnames, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

And this week, reporter Todd Feathers broke the news for The Markup that hundreds of universities are using risk assessment algorithms to predict which students are likely not to graduate within their chosen major.

Todd obtained documents from four large universities that showed that they were using race as predictor, and in some cases a “high impact predictor” in their risk assessment algorithms. In criminal justice risk algorithms, race has not been included as an input variable since the 1960s.

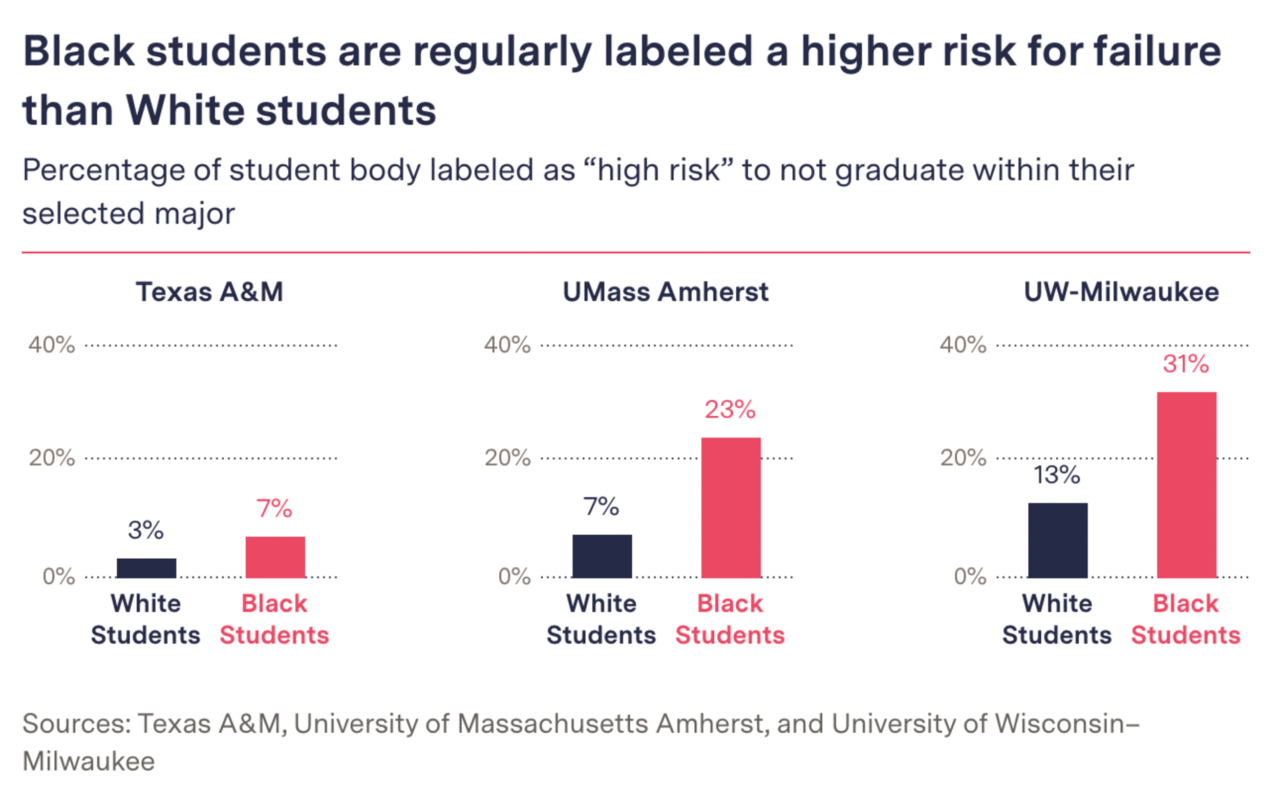

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, the University of Houston, and Texas A&M University the software predicted that Black students were “high risk” at as much as quadruple the rate of their White peers.

Representatives of Texas A&M, UMass Amherst, and UW-Milwaukee noted that they were not aware of exactly how EAB’s proprietary algorithms weighed race and other variables. A spokesperson for the University of Houston did not respond specifically to our request for comment on the use of race as a predictor.

The risk assessment software being used by the universities is called Navigate and is provided by an education research company called EAB. Ed Venit, an EAB executive, told Todd it is up to the universities to decide which variables to use and that existence of race as an option is meant to “highlight [racial] disparities and prod schools to take action to break the pattern.”

If the risk scores were being used solely to provide additional support to the students labeled as high risk, then perhaps the racial disparity would be less concerning. But faculty members told Todd that the software encourages them to steer high-risk students into “easier” majors—and particularly, away from math and science degrees.

“This opens the door to even more educational steering,” Ruha Benjamin, a professor of African American studies at Princeton and author of “Race After Technology,” told The Markup. “College advisors tell Black, Latinx, and indigenous students not to aim for certain majors. But now these gatekeepers are armed with ‘complex’ math.”

There are no standards and no accountability for the ‘complex math’ that is being used to steer students, rate tenants, and rank criminal defendants. So we at The Markup are using the tools we have at our disposal to fill this gap. As I wrote in this newsletter last week, we employ all sorts of creative techniques to try to audit the algorithms that are proliferating across society.

It’s not easy work, and we can’t always obtain data that lets us definitively show how an algorithm works. But we will continue to try to peer inside the black boxes that have been entrusted with making such important decisions about our lives.

As always, thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup