Hello, friends,

One year ago, The Markup officially launched, setting out to investigate how the world’s most powerful institutions are using technology to reshape society. It was a big idea for a small nonprofit newsroom, but the moment called for it. With blackbox algorithms reaching into every corner of culture and trillion-dollar tech conglomerates surveilling our most personal data for private gain, there was a growing need for greater accountability in tech. And that’s what independent, investigative journalism does best.

Our first investigation was an examination of Allstate’s secret algorithm for setting car insurance prices, which we found was charging higher prices to people who it predicted were less likely to shop around. It was, perhaps, not the most obvious first story for a newsroom with the tagline “Big Tech Is Watching You. We’re Watching Big Tech.” Most people likely don’t think of car insurance as Big Tech. But, like many things in our lives, it is.

If we have learned anything from this past year, it is that Big Tech is everything and everywhere. From Zoom conference calls to contactless food delivery to remote schooling to vaccine scheduling, technology is the gateway to everything from luxuries to life or death resources.

Most of these automated services we rely on are run by inscrutable algorithms that are impossible for the public to understand, and that’s not right. We at The Markup believe that the public deserves to know how technology is being used to make decisions that affect people’s lives.

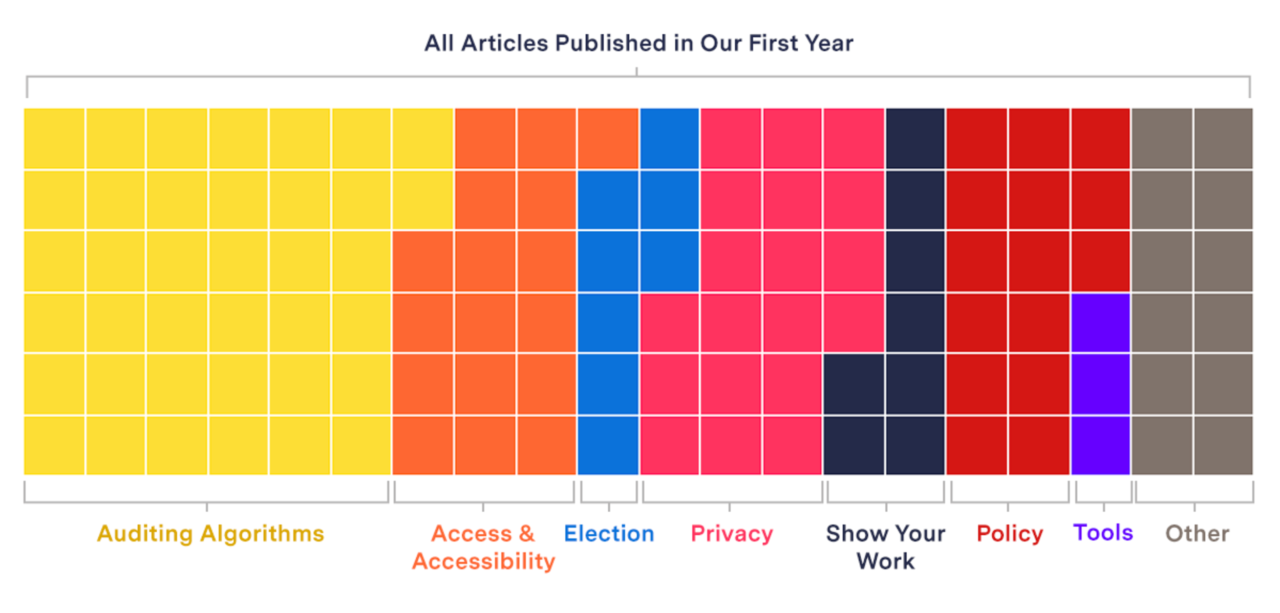

So that is why I am thrilled to report that when we ran the numbers of what The Markup covered in its first year of publishing, stories that audited algorithms were the bulk of our coverage, followed by our two other favorite topics—privacy and inequitable access to technology.

Auditing algorithms is hard work, and as The Markup reporter Alfred Ng wrote this week, there are no agreed-upon standards for how auditors should independently assess algorithmic performance. It’s even harder for journalists, who are not being invited in to do an audit but are attempting to understand algorithms from the outside.

So I thought it would be interesting to review the different approaches we have taken to auditing algorithms so far.

The Secret Document. The Allstate investigation was powered by a document that investigative data journalist Maddy Varner obtained through a public records request to Maryland insurance regulators. The document we obtained listed the prices that Allstate was proposing to charge to every one of its customers in Maryland. This allowed us to do some fancy math to analyze their algorithm and show that it was a suckers list that aimed to squeeze big spenders.

The Experiment. To analyze how Gmail’s algorithm sorts email into different inboxes, we designed an experiment. Investigative reporter Adrianne Jeffries set up a new Gmail account and subscribed to hundreds of political email newsletters to see how Gmail would sort them when they arrived. She and investigative data journalist Leon Yin found that there was wide and seemingly arbitrary variation between the political newsletters that were sorted into the primary inbox and those sorted into the less-visible “promotions” inbox.

Scrape and Classify. Investigative data journalist Leon Yin measured how often Google boosted its own products to the top of the search results page by scraping more than 15,000 search results and then building classifiers to help us sort out which results were Google products and which were not. (We accounted for different interpretations of each category in the full methodology.) The result? We were able to find that Google gives itself 41 percent of the first page and 63 percent on the first screen of a mobile device.

The Tool. Investigative data journalist Surya Mattu took the “scrape and classify” approach to another level when he built Blacklight, a privacy forensics tool that lets readers analyze how third parties are exploiting user data on any website. When a user enters a URL into Blacklight, it instantly visits the page and runs several tests to see if the site is using any invasive techniques, such as recording keystrokes and mouse movements or “fingerprinting” the visitors’ computer.

The Honey Pot. Investigative reporter Aaron Sankin has covered internet hate groups for a long time, and the result of his searching for a lot of unsavory content is that he is also targeted with unsavory content. This is what hackers call turning yourself into a “honey pot”—meaning you make yourself look like an attractive target for whatever it is you are searching for. This is likely why Facebook saw him as someone interested in “pseudoscience” and targeted him with ads for a radiation-blocking hat, and how he discovered that Facebook had created a linked network of Holocaust denial pages and groups. Both examples allowed us to show how the platform’s algorithm wasn’t doing what it promised.

Court Records. When we heard that landlords were using software to assign risk scores to potential renters, we struggled to figure out how to tackle the story. Investigative reporter Lauren Kirchner sought and obtained public records for what kinds of software public housing authorities were using, but we couldn’t get data about how many people were incorrectly denied housing by mistaken risk scores, and the private housing market was still a mystery.

So we ended up using the old-school technique of scouring court records to find out how many people had filed claims against the software makers for harmful errors. It took months, but we ended up with a striking database of cases that showed a clear pattern of sloppy and life-altering mistakes by the algorithms.

The Panel. To understand how Facebook’s algorithms target information to different groups of people, we set up a national panel of users who let us monitor their Facebook feeds. The Citizen Browser project is probably our most ambitious—and expensive!—attempt to audit an algorithm, but it has already yielded insights that we could not have gotten any other way, including the fact that Facebook never labeled any of Trump’s posts “false” and that Facebook broke its promise to Congress to turn off political group recommendations.

As you can see from this list, each story demands its own technique. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to auditing the algorithms that determine the architecture of our lives.

And truthfully it’s kind of insane that we have to do this amount of engineering and data analysis. If we were reporters covering another industry—say airlines—we would likely spend much more of our time on traditional reporting techniques, such as filing public record requests to the Federal Aviation Administration, which is responsible for ensuring safety of airplanes. We likely wouldn’t be trying to inspect the planes ourselves (although perhaps the 737 Max disaster makes the case that someone should be).

But there is no regulatory body that oversees Big Tech, and so we do these insanely heavy lifts because we believe the public needs to know how we are being sorted and judged by automated systems.

And that’s not all we did this year. We filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court to defend journalists’ right to scrape public information from the internet. We built tools to protect the privacy of our readers. This week we launched our first-ever annual report, beautifully conceived and designed by Markup president Nabiha Syed and her team, which nicely captures all of the work we have done and the impact we have had.

In the year since we published our first story, Big Tech has only gotten much bigger, which means The Markup is called on to shoulder even more weight. It’s in that spirit that we’re launching our first-ever annual giving campaign. We couldn’t do what we do without reader support. If you would entrust us with a tax-deductible contribution in any amount, it would be our honor to use it to hold Big Tech to account.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup