Hello, friends,

As you know, we love to analyze algorithms here at The Markup. The more complex and secretive it is, the more excited we are to deconstruct it. That’s why we’ve taken deep dives into Allstate’s individualized pricing algorithm and Gmail’s inbox sorting algorithm.

Recently we decided to look into what seemed like simpler algorithms: how third-party sellers set prices on Amazon.com. If you’re like us, you’ve probably spent some of your time during quarantine being frustrated by the high prices of basic items on the site. At one point, to give a couple of examples, prices on Amazon for black beans jumped eight-fold from $3.17 to $24.50, and the cost of flour in some cases quintupled to $110 from $22.

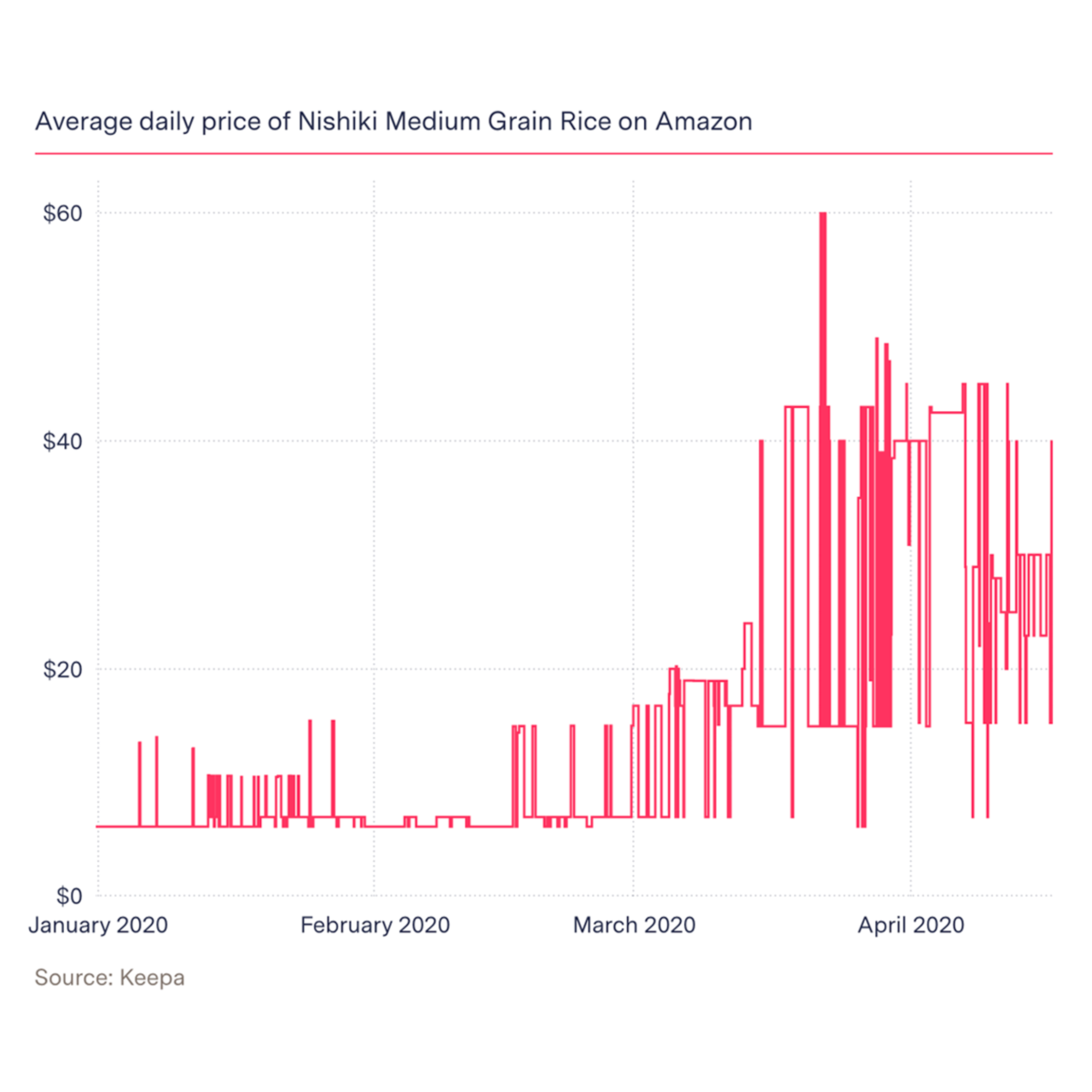

Consider this chart of the price of a five-pound bag of Nishiki rice, which has careened from $10 to as high as $60 in the past two months.

Of course, some of the volatility was based on supply and demand. As Will Oremus delightfully explained in The Marker, the toilet paper shortage was due to a huge surge in demand. With everyone suddenly staying home, the average household was predicted to use 40% more toilet paper than before.

And it’s not easy for manufacturers of staple items—where demand is usually stable—to ramp up production quickly. After demand surged for dry yeast, Fleischmann’s Yeast sold out two to three weeks of supply almost instantly, according to an interview in USA Today with John Heilman, vice president of yeast manufacturing for Fleischmann’s parent company, AB Mauri. He said it will likely take the company one to two months to ramp up production enough to get store shelves stocked with yeast again.

It turns out, though, that there is more to the wildly fluctuating prices on Amazon than just supply and demand. Reporter Sara Harrison explored the nuances of dynamic pricing algorithms on Amazon in this week’s Ask The Markup. She found that price volatility on Amazon is exacerbated when vendors pit pricing algorithms against each other to win the coveted “Buy Box”—which is the default vendor that users get when they click Add to Cart.

In a 2016 study, third-party sellers who used algorithmic pricing would change their prices tens or even hundreds of times every day as they wrestled for the Buy Box, according to researchers at Northeastern University, who tracked the prices of more than 16,000 items on Amazon. Those sellers were more likely to win a spot in the Buy Box.

But when sellers configure their algorithms to always set prices just slightly above the price of their competition, the constant price changes can lead to skyrocketing costs for consumers. In one bizarre instance, two competing algorithms drove the price of a science textbook up to $24 million.

Such extremes could be avoided if price ceilings were set for certain products, but while Amazon has said that it is cracking down on price-gouging, it lets sellers set their own prices, and the U.S. government does not set price caps.

And that means you should expect the price of rice to continue to fluctuate on Amazon. If you want to try to avoid paying too much, you may want to try an Amazon price-tracking browser extension such as Camelcamelcamel or Keepa.

Good luck with your online shopping, and thanks, as always, for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup