Multi-level marketing companies sometimes face allegations of operating as pyramid schemes, in part because of how they’re structured. In both illegal pyramid schemes and legal multi-level marketing companies, sales representatives sell products or services while recruiting people to join them. These businesses have captured the zeitgeist in recent years, thanks to docuseries (LuLaRich) and podcasts (“The Dream“) exploring their ills.

What receives far less attention is the software that powers these companies. In the digital age, software firms are what enable the multi-level marketing industry to do its work. And experts have been weighing how culpable software companies may be if their customer turns out to be a pyramid scheme.

“It is a very dangerous space to be in,” said Mark Eiglarsh, a criminal defense lawyer who has handled multi-level marketing cases before. “The onus is on [the software companies] to do everything they can to vet the companies they do business with, so not if, but when, a prosecutor questions them, they say, ‘Here are the lengths we took.’”

Software companies that serve multi-level marketing firms have been around for more than two decades. This sub-industry often works with smaller- and medium-sized multi-level marketing companies that don’t have the resources to build their own software. These companies are also distinct from payment processors like Square or Stripe, which aren’t designed for the multi-level marketing industry’s specific needs.

At its most expansive, multi-level marketing software can be a company’s backbone, structuring commissions, tracking sales, and identifying whether sales representatives are meeting their targets. When participants in a multi-level marketing firm want to track the money they earn from selling products or the new members they bring in, they often log into a portal provided by companies like Florida-based ByDesign Technologies.

In the digital age, software firms are what enable the multi-level marketing industry to do its work.

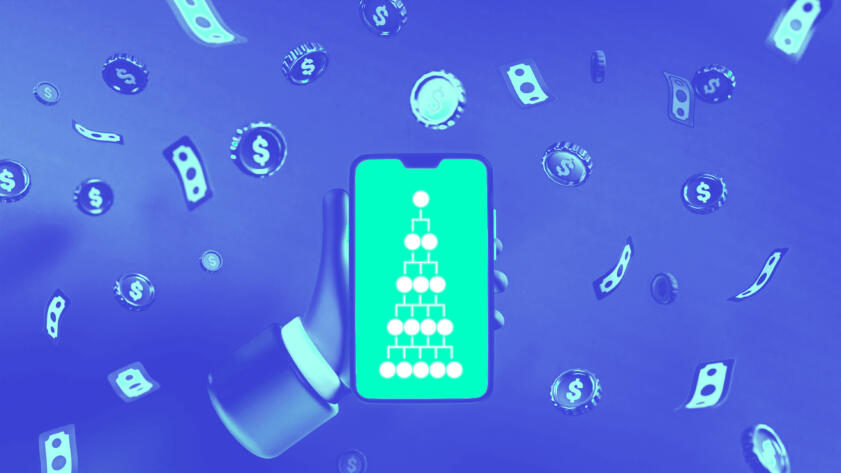

But what makes this software different from other offerings is its ability to customize the industry’s unique compensation structures. While there is some variation, compensation structures at a multi-level marketing company typically look like an upside down tree—each new person brought in is added to an existing sales representative’s “branch.” In addition to being paid for sales of a product or service, sales representatives can also be paid for what those below them on this tree bring in. As the company grows, this structure can become sprawling. Software helps manage this.

“Technology and technology provision is probably one of the biggest challenges for direct selling companies,” said Joseph Mariano, president of the Direct Selling Association trade group, “as it is for almost any business these days.”

The Direct Selling Association represents companies that account for nearly 90 percent of the multi-level marketing industry’s total sales volume, Mariano said. Its site lists 92 members, ranging from household names such as Amway and Herbalife to smaller shops. Several software companies, listed among its 129 suppliers, sponsored the Direct Selling Association’s annual conference this year, including Jenkon, Exigo, and Flight Commerce.

But multi-level marketing software can also allow for problematic customizations.

Machine Learning

AI Detection Tools Falsely Accuse International Students of Cheating

Stanford study found AI detectors are biased against non-native English speakers

“The narrative of [a multi-level marketing company] is, ‘We’re providing you with an opportunity, and the people you see being successful have the same opportunity we’re offering you,’” said William Keep, former marketing professor at The College of New Jersey, who’s served as an expert witness in multi-level marketing lawsuits. But that narrative is not always true.

For example, some multi-level marketing companies quietly allow certain new participants to come into the company higher up on the tree than others, he said, giving them a greater chance at success because of the established line of people below them helping bring in sales or meet a company’s minimum sales requirements. Others may move people from one “branch” to another, which can change the earnings of those affected. Pyramid schemes may also move new participants higher up on the tree, but solely moving people around doesn’t equate to illegal activity.

“That doesn’t mean the company who creates the software is making these decisions,” Keep said. “They’re being told this is how we want the software to work.”

Legal landscape: Pyramid schemes vs. multi-level marketing companies

Pyramid schemes, which are illegal, can look “remarkably like” multi-level marketing companies, according to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). How compensation works is one of the main factors regulators use to differentiate them.

Regulators use a two-pronged test to determine if a company is operating as a pyramid scheme:

- If a company's sales representatives are required to pay to sell its products or services,

- And if its sales representatives can earn “rewards” outside of sales to actual customers, such as payment for recruiting.

“You’ve got to look at the money flow,” said Lois Greisman, associate director of the FTC’s marketing practices division. “You’ve got to actually look at the incentive structure and where incentives are.”

Direct Selling Association members are required to follow a code of ethics to maintain their membership status, including prohibiting sales representatives from getting paid to recruit other sales people, Mariano said, except for “minimal incentives” within the bounds of the law.

But as for whether software companies hold accountability when servicing a multi-level marketing company accused of being a pyramid scheme, it comes down to the details.

Regulators take the position that basically, if you contribute to the illegality of something and know—or reasonably should know—what it’s doing, then you can be liable for it.

Rebecca Tushnet, Harvard Law School professor

Being aware of complaints against a customer or having some knowledge that its platform is being used for illicit activity can make them culpable, according to Harvard Law School professor Rebecca Tushnet.

“Regulators take the position that basically, if you contribute to the illegality of something and know—or reasonably should know—what it’s doing, then you can be liable for it,” Tushnet said.

For instance, the FTC previously sued technology companies that enabled illegal robocalls through their Voice over Internet Protocol products, despite the companies not being behind the calls themselves.

And then there’s the compensation structure. Stacie Bosley, economics professor at Hamline University, said software companies should look for a “disconnect” between sales representatives’ income from actual sales versus income from recruitment. If their income is heavily slanted toward recruitment, that should be a red flag, she said.

But this kind of analysis can bring in a thorny question of privacy and whether this hurts customers’ trust in the software companies, Eric Goldman, law professor at Santa Clara University, said.

Mariano said many software companies in this space advise their multi-level marketing clients on how to be compliant with the law.

One company, Rallyware, provides software to multi-level marketing and other kinds of companies, but doesn’t provide compensation management as a service. Even so, their contracts with clients specify that those companies make money in ways that are within the bounds of the law, according to Rallyware Senior Writer Alec Niedenthal.

Software companies have testified in court

Several multi-level marketing-focused software companies The Markup contacted for this article declined or did not reply to interview requests. But a legal case sheds light on how intertwined these companies can be with multi-level marketing companies and potential pyramid schemes.

In 2017, the FTC sued the leadership of a multi-level marketing company called Infinity 2 Global, which purported to be an investment opportunity. Keep testified as an expert witness for the case. The federal government alleged that Infinity 2 Global was a pyramid and Ponzi scheme. Its operations were made possible through a software platform provided by Texas-based Trinity Software.

Trinity advertises “the most advanced sales tools for [multi-level marketing] & party plan organizations. Bar none.” Its software allows multi-level marketing companies to pay their sales representatives commissions and track what customers are buying, among other features. While Trinity was not sued as part of the case, its CEO was called by regulators to testify.

Trinity created the infrastructure for how compensation was handled at Infinity 2 Global, and had access to information on sales activity, bonuses, where people sat in the company’s structure, how much each product contributed to the company’s overall profits, and what the company’s profit margin was. Its software also enabled shifting people around in the compensation “tree,” which could affect their income; Trinity CEO Jerry Reynolds testified that his company refuses to do this itself, and instead, Trinity coaches customer companies to get written permission from everyone affected by a shift like this before changing the compensation “tree.”

The specifics of this data were used by the federal government to argue that Infinity 2 Global operated as a pyramid scheme. Reynolds testified that he would not work with any company if he thought its compensation plan wasn’t workable. When asked if Trinity looks for patterns in this information, such as “who it was distributed to and who won and who lost,” Reynolds said his company does not.

“I don’t because it’s private,” he testified. “If they start having difficulty paying, then I’m going to run some queries and see if their business is tailing off so that I can prepare as a businessman that… I’m about to not get paid.”

Reynolds did not respond to requests for an interview.

Three leaders of the scheme were convicted of conspiracy to commit mail and securities fraud, and one was additionally convicted of money laundering and attempted tax evasion after prosecutors “proved at trial [the company] was operating as a pyramid scheme,” according to a 2022 release from the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Kentucky’s western district. Two of them were sentenced to 10 years and 4 years in prison, one of whom was ordered to pay a $100,000 fine. They were also ordered to pay restitution to victims. One of the defendants is currently appealing.

Mariano said that not all software companies have access to financial information such as the actual sales for a company. For those that do, he said culpability would depend on “the facts of each of those circumstances.”