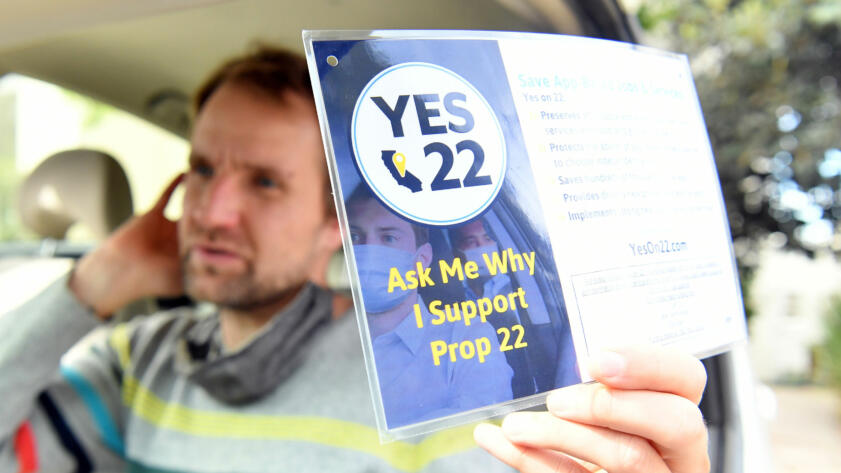

It was expensive—about $205 million, the most ever spent on a ballot initiative—and certainly unconventional, but Uber, Lyft, and Instacart gladly paid the price for passing Proposition 22, which classifies app-based drivers as contractors, an exemption to California’s law that would otherwise require that they receive full employee benefits. Emboldened, tech company executives have already started talking about how to cement a non-employee status for gig workers across the country and even the world.

Shortly after the Nov. 3 victory, according to TechCrunch, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said in an earnings call that he will “more loudly advocate for laws like Prop 22,” and that the company will prioritize working “with governments across the U.S. and the world to make this a reality.”

Similarly, Lyft’s co-founder John Zimmer told Axios he wants to “create certainty so that we can build more jobs. And do it state by state if we need to. It would be easier to do it at the federal level, but we’re just going to have to see how it plays out.” And Taylor Bennett, DoorDash’s global head of public affairs, told The Markup the company is “ready to work with legislators everywhere on policies that protect Dasher flexibility and extend portable and proportional benefits.”

Uber and Lyft declined to comment for this story.

The companies’ success in one of the most politically liberal states—and one where the legislature explicitly attempted to require companies to treat their drivers as employees—is not lost on activists fighting against what they see as the creation of a “permanent underclass of workers.”

“This was California’s fight,” Carlos Ramos, a driver and organizer with Gig Workers Rising, told The Markup. “Now this is America’s fight.”

So where, exactly, will the battle go next?

New York State May Be Next in Line

Because of its sheer market size, New York City—and therefore, New York State—is a crucial target.

Uber has already started New York–specific social media advertisements aimed at garnering public support for “a plan that gives gig drivers like me new benefits I need and the flexibility I want.”

A linked article from the advertisement asks that when “leadership in New York picks back up the conversation, they do so with people like me in mind. Consider ways to support workers while also guaranteeing that we can keep our flexibility and independence.”

“I think this movement is well under way,” said Erin Hatton, a sociologist focusing on labor issues at the University at Buffalo. “New York is really important.”

In 2018, New York City passed a law requiring a minimum payment scheme for gig workers.

This year, New York City council member Brad Lander, an advocate for classifying gig workers as employees, proposed a bill that would create a three-part test for employment in New York City that would make gig workers employees for the purposes of the city’s Earned Safe and Sick Time Act. Lander is also the co-sponsor of a resolution recommending that the state broaden the definition of employee to include gig workers.

In January, New York governor Andrew Cuomo planned to commission a study on gig worker classification, but once the coronavirus pandemic broke out, the study was not included in the state budget.

Several competing bills have been floating around the New York State legislature for a few years, with Democrats split in their support or opposition to cementing gig workers in their contractor status: One bill would define gig workers as employees; another would remove the issue of flexible versus rigid working hours from the debate over gig employee rights. Yet another would create a special status for gig workers, making them neither employees nor contractors, but give them the right to unionize as a group, known as sectoral collective bargaining. The bill removing flexibility from the debate passed the senate last year but failed in the assembly, and it now has returned to the senate labor committee for reconsideration. The two others have not left the senate labor committee.

Brian Chen of the National Employment Law Project said to also expect forthcoming Prop 22–like legislation in New York State, as companies have been laying the groundwork for public and lawmaker support.

A report from the Public Accountability Initiative (PAI) found that an Uber- and Lyft-backed group, Flexible Work for New York (run by public relations and lobbying firm SKDKnickerbocker on a pro bono basis), as well as the Lyft-backed New Yorkers for Independent Work, have spent more than $1.1 million on Democratic candidate campaigns in the New York State assembly and senate.

Uber’s head of work communications, Matthew Wing, is a former Cuomo communications director and is married to a current top Cuomo aide, Melissa DeRosa. Another former Cuomo staffer, David Yassky, has lobbied for Lyft since 2014, PAI found.

All in all, between January 2017 and June 2020, Uber and Lyft have spent a combined $11.5 million lobbying in New York State using 16 different firms, according to public data compiled by PAI.

“With the infrastructure in place in New York, it seems only a matter of time before gig economy employers make their next major attack on workers’ rights,” wrote Rob Galbraith, the author of the PAI report.

Other States

The Coalition to Promote Independent Entrepreneurs, which supports more workers being classified as independent contractors, estimates that 26 states currently have laws defining employee status, for purposes of filing unemployment, that could give gig workers an avenue for claiming full employee benefits through the courts. In most of them, however, the gig worker question has not been litigated.

The pro–independent contractor group is also tracking employment classification bills in 12 states that could impact how gig workers are defined.

New Jersey, Connecticut, and Massachusetts are among the states with laws defining employee status where the gig worker question has been litigated, but mandatory arbitration agreements that the gig companies require drivers to sign have so far slowed drivers’ attempts to sue.

Earlier this year, New Jersey legislators introduced a bill specifically designed to classify gig workers as employees; the bill has not come up for a vote yet. In January, New Jersey governor Phil Murphy also signed five pro-employee laws. One of them makes gig economy executives themselves personally liable for misclassifying employees.

Last year, New Jersey fined Uber $650 million for not paying unemployment and disability insurance taxes.

In July, the Massachusetts state attorney general sued Uber and Lyft for allegedly misclassifying drivers as contractors.

At the Federal Level, a Lot Depends on Georgia’s Special Election

Any plans for federal legislation specifically addressing gig workers’ status rests heavily on what happens in Georgia’s special election to fill two U.S. Senate seats, scheduled for Jan. 5, which will determine which political party controls the Senate.

Should Democrats win, there’s some hope for proponents of the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which passed the Democrat-controlled U.S. House in February but failed in the Senate. The legislation would strengthen a wide slew of labor and employment laws, and it includes a provision defining gig workers as employees.

Tech companies have certainly taken notice: Uber and Lyft each spent more than $1.2 million lobbying the federal government in the first half of 2020, according to Open Secrets, with the bill most cited (along with the coronavirus relief CARES Act) being the PRO Act.

And support for the bill among Democrats is not universal.

“I don’t think it strictly folds along party lines as one might expect,” said Hatton, the University at Buffalo sociologist.

Senator Mark Warner (D-VA) said through a spokesperson in a statement to The Markup that “voters all over the country made it clear that policymakers should take a nuanced approach to the labor market.

“We know that independent workers are not all the same—some are misclassified or would prefer to be treated as full-time employees, while others genuinely prefer to be independent contractors and use this kind of work to supplement other employment,” he said. Warner has not stated a position on the PRO Act.

As President, Joe Biden Could Weigh in on the Debate Pretty Quickly

Biden came out against Proposition 22 in his presidential campaign, but he also has tight connections to the tech world. Many former Obama administration officials have migrated to Silicon Valley, including former secretary of transportation Anthony Foxx, who is now chief policy officer at Lyft. David Plouffe, Obama’s 2008 campaign manager, was Uber’s senior vice president for policy until 2017, according to the Public Accountability Initiative. In 2017, he was fined for lobbying Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel (also an Obama alum) on behalf of Uber without registering.

Seth Harris—one of the authors of a 2015 paper outlining a separate category for gig workers and former acting Secretary of Labor under Obama—sits on Biden’s Department of Labor transition team. Anita Dunn, a top Biden adviser, is a partner at SKDKnickerbocker, the PR and lobbying firm running the Uber- and Lyft-backed front group, PAI found.

There could be forces in a Biden administration that either cut a bad deal or [are] on the side of the tech monopolies in this fight. I hope that won’t happen.

Brad Lander, NYC Council

Vice President–elect Kamala Harris’s deep ties to big tech are well reported, and her record as attorney general with them is mixed. Tony West, chief legal officer for Uber, is her brother-in-law and a longtime top adviser.

“There could be forces in a Biden administration that either cut a bad deal or [are] on the side of the tech monopolies in this fight. I hope that won’t happen,” said New York City council member Lander.

Should Biden choose to do so, he could pretty quickly weigh in on the fate of gig workers by rolling back a proposed administrative change the Trump administration made in September that would make it harder for gig workers to claim employee status. The comment period has ended, but the rule has yet to be finalized.

The National Labor Relations Board’s current general counsel, Peter Robb (a Reagan administration anti-union litigator), has opined that Uber drivers are independent contractors, and unless Biden fires him, as labor advocates hope, his term won’t expire until November 2021. So long as he keeps his post, the federal government is unlikely to advocate for gig workers’ employee status.