The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

If you’ve hunted for apartments recently and felt like all the rents were equally high, you’re not crazy: Many landlords now use a single company’s software — which uses an algorithm based on proprietary lease information — to help set rent prices.

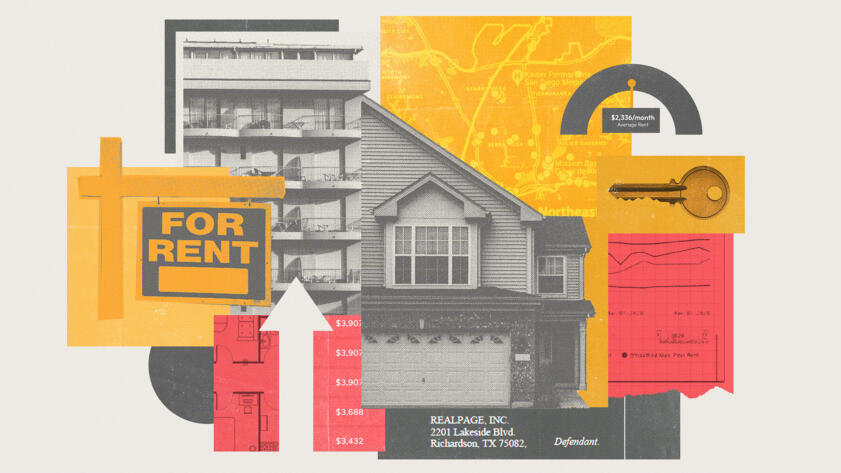

Federal prosecutors say the practice amounts to “an unlawful information-sharing scheme,” and some lawmakers throughout California are moving to curb it. San Diego’s city council president is the latest to do so, proposing a ban that would prevent local apartment owners from using the pricing service, which he maintains is driving up housing costs.

San Diego’s proposed ordinance, which is currently being drafted, comes after San Francisco enacted a first-in-the-nation ban on “the sale or use of algorithmic devices to set rents or manage occupancy levels” for residences in July. San Jose is considering a similar approach.

Similar bans have passed or are being considered across the country. In September, The Philadelphia City Council passed a ban on algorithmic rental price-fixing with a veto-proof vote. New Jersey has been considering its own ban.

In August, The Department of Justice and the attorney generals of eight states — California, North Carolina, Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota, Oregon, Tennessee, and Washington — filed an antitrust lawsuit against RealPage, the leading rental pricing platform based in Texas. The complaint alleges that “RealPage is an algorithmic intermediary that collects, combines, and exploits landlords’ competitively sensitive information. And in so doing, it enriches itself and compliant landlords at the expense of renters who pay inflated prices…”

RealPage has been a major impetus for all of the actions. Some officials accuse the company of thwarting competition that would otherwise drive rents down, exacerbating the state’s housing shortage and driving up rents in the process.

“We are disappointed that, after multiple years of education and cooperation on the antitrust matters concerning RealPage, the (Justice Department) has chosen this moment to pursue a lawsuit that seeks to scapegoat pro-competitive technology that has been used responsibly for years,” the company’s statement read in part. “RealPage’s revenue management software is purposely built to be legally compliant, and we have a long history of working constructively with the (department) to show that.”

Locked Out

Access Denied: Faulty Automated Background Checks Freeze Out Renters

Computer algorithms that scan everything from terror watch lists to eviction records spit out flawed tenant screening reports. And almost nobody is watching

“Every day, millions of Californians worry about keeping a roof over their head and RealPage has directly made it more difficult to do so,” said California Attorney General Rob Bonta in a written statement.

A RealPage spokesperson, Jennifer Bowcock, told CalMatters that a lack of housing supply, not the company’s technology, is the real problem — and that its technology benefits residents, property managers, and others associated with the rental market. The spokesperson later wrote that a “ misplaced focus on nonpublic information is a distraction… that will only make San Francisco and San Diego’s historical problems worse.”

As for the federal lawsuit, the company called the claims in it “devoid of merit” and said it plans to “vigorously defend ourselves against these accusations.”

In 2020, a Markup and New York Times investigation found that RealPage, alongside other companies, used faulty computer algorithms to do automated background checks on tenants. As a result, tenants were associated with criminal charges they never faced and denied homes.

Is it price fixing—or coaching landlords?

According to federal prosecutors, RealPage controls 80% of the market for commercial revenue management software. Its product is called YieldStar, and its successor is AI Revenue Management, which uses much of the same codebase as YieldStar, but has more precise forecasting. RealPage told CalMatters it serves only 10% of the rental markets in both San Francisco and San Diego, across its three revenue management software products.

Here’s how it works:

In order to use YieldStar and AIRM, landlords have historically provided RealPage with their own private data from their rental applications, rent prices, executed new leases, renewal offers and acceptances, and estimates of future occupancy, although a recent change allows landlords to choose to share only public data. This information from all participating landlords in an area is then pooled and run through mathematical forecasting to generate pricing recommendations for the landlords and for their competitors.

The San Diego council president, Sean Elo-Rivera, explained it like this:

Our tool ensures that [landlords] are driving every possible opportunity to increase price even in the most downward trending or unexpected conditions.

RealPage document included in federal antitrust lawsuit

“In the simplest terms, what this platform is doing is providing what we think of as that dark, smoky room for big companies to get together and set prices,” he said. “The technology is being used as a way of keeping an arm’s length from one big company to the other. But that’s an illusion.”

In the company’s own words, from company documents included in the lawsuit, RealPage “ensures that (landlords) are driving every possible opportunity to increase price even in the most downward trending or unexpected conditions.” The company also said in the documents that it “helps curb (landlords’) instincts to respond to down-market conditions by either dramatically lowering price or by holding price.”

Impact on tenants

Thirty-one-year-old Navy veteran Alan Pickens and his wife move nearly every year “because the rent goes up, it gets unaffordable, so we look for a new place to stay,” he said. The northeastern San Diego apartment complex where they just relocated has two-bedroom apartments advertised for between $2,995 and $3,215.

They live in an area of San Diego where the U.S. Justice Department says information-sharing agreements between landlords and RealPage have harmed or are likely to harm renters.

The rent goes up, it gets unaffordable, so we look for a new place to stay.

Alan Pickens, resident of a San Diego neighborhood where pricing software allegedly harmed renters or is likely to do so

The department in August filed its antitrust lawsuit against RealPage, alleging the company, through its legacy YieldStar software, engaged in an “unlawful scheme to decrease competition among landlords in apartment pricing”. The complaint names specific areas where rents are artificially high. Beyond the part of San Diego where Pickens lives, those areas include South Orange County, Rancho Cucamonga, Temecula, and Murrieta and northeastern San Diego.

In the second quarter of 2020, the average rent in San Diego County was $1,926, reflecting a 26% increase over three years, according to the San Diego Union-Tribune. Rents have since risen even more in the city of San Diego, to $2,336 per month as of November 2024 – up 21% from 2020, according to RentCafe and the Tribune. That’s 50% higher than the national average rent.

The attorneys general of eight states, including California, joined the Justice Department’s antitrust suit, filed in U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina.

The California Justice Department contends RealPage artificially inflated prices to keep them above a certain minimum level, said department spokesperson Elissa Perez. This was particularly harmful given the high cost of housing in the state, she added. “The illegally maintained profits that result from these price alignment schemes come out of the pockets of the people that can least afford it.”

Renters make up a larger share of households in California than in the rest of the country — 44% here compared to 35% nationwide. The Golden State also has a higher percentage of renters than any state other than New York, according to the latest U.S. Census data.

San Diego has the fourth-highest percentage of renters of any major city in the nation.

The recent ranks of California legislators, however, have included few renters: As of 2019, CalMatters could find only one state lawmaker who did not own a home — and found that more than a quarter of legislators at the time were landlords.

Studies show that low-income residents are more heavily impacted by rising rents. Nationally between 2000 and 2017, the percentage of income that Americans without a college degree spent on rent ballooned from 30% to 42%. For college graduates, that percentage increased from 26% to 34%.

“In my estimation, the only winners in this situation are the richest companies who are either using this technology or creating this technology,” said Elo-Rivera. “There couldn’t be a more clear example of the rich getting richer while the rest of us are struggling to get by.”

The state has invested in RealPage

Private equity giant Thoma Bravo acquired RealPage in January 2021 through two funds that have hundreds of millions of dollars in investments from California public pension funds, including the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, the Regents of the University of California and the Los Angeles police and fire pension funds, according to Private Equity Stakeholder Project.

“They’re invested in things that are directly hurting their pensioners,” said K Agbebiyi, a senior housing campaign coordinator with the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, a nonprofit private equity watchdog that produced a report about corporate landlords’ impact on rental hikes in San Diego.

RealPage argues that landlords are free to reject the price recommendations generated by its software.

RealPage argues that landlords are free to reject the price recommendations generated by its software. But the U.S. Justice Department alleges that trying to do so requires a series of steps, including a conversation with a RealPage pricing adviser. The advisers try to “stop property managers from acting on emotions,” according to the department’s lawsuit.

If a property manager disagrees with the price the algorithm suggests and wants to decrease rent rather than increase it, a pricing advisor will “escalate the dispute to the manager’s superior,” prosecutors allege in the suit.

In San Diego, the Pickenses, who are expecting their first child, have given up their gym memberships and downsized their cars to remain in the area. They’ve considered moving to Denver.

“All the extras pretty much have to go,” said Pickens. “I mean, we love San Diego, but it’s getting hard to live here.”

“My wife is an attorney and I served in the Navy for 10 years and now work at Qualcomm,” he said. “Why are we struggling? Why are we struggling?”