Everything was already packed into boxes, and she just had to go pick up the keys. Rafaela Aldaco had been struggling financially for years, raising two kids on her own, and now she was thrilled to have been accepted into a nonprofit transitional housing program in the suburbs of Chicago geared toward single moms in danger of homelessness. The program would both help her pay her rent at a new place and pay back old debts—a lifeline.

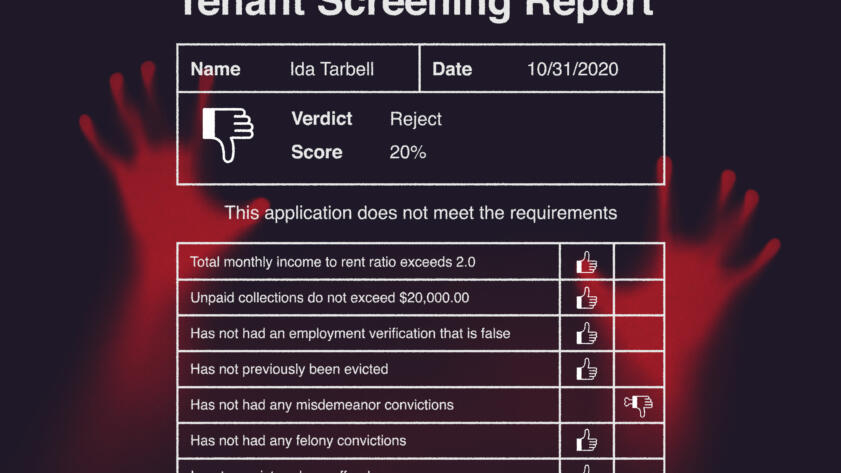

When she showed up at the apartment, though, she was told there was a problem. A tenant-screening report had surfaced something she’d rather forget, an altercation with her then-boyfriend when she was 18. At the time, she had taken five days of community service and six months of probation in exchange for having her record dismissed. But there it was on her Rentgrow screening report, almost 20 years later. She was turned away from the apartment, and the program. She drove her boxes to a storage facility.

“She was all excited about it,” Aldaco’s friend from her church’s Bible study group, Clementine Frazier, told lawyers in the court case Aldaco later filed against Rentgrow, “and then when it didn’t happen, she was devastated. Because she had nowhere to go.”

… when it didn’t happen, she was devastated. Because she had nowhere to go.

Clementine Frazier

Aldaco lost her 2016 case against Rentgrow in 2018, when a federal judge in the Northern District of Illinois ruled that her guilty plea was essentially the same thing as a conviction under federal law and therefore reportable in a background check. The appellate court agreed.

Rentgrow declined to comment on any litigation, as did the other screening companies mentioned in this article, RealPage and its subsidiary On-Site, but an industry trade group that represents those companies provided a statement to The Markup.

“Background check companies want to provide accurate criminal history information not just because the law requires it, but because it’s the right thing to do,” said Eric Ellman, senior vice president of public policy and legal affairs of the Consumer Data Industry Association. “Our members report facts as they are provided by courthouses across the country, and our members do not interpret that information for their landlord clients. Our members do not report sealed or expunged information if they know that the record is sealed or expunged, and our background check members regularly update court record information from courts across the U.S.”

Still, stories like Adalco’s are remarkably common.

Tenant screening companies have increasing sway over who does and does not get a given home—an estimated nine out of 10 landlords, under pressure to ensure their properties are safe, use companies like Rentgrow to perform background checks on potential tenants. Public housing authorities and nonprofit anti-homelessness programs use them too.

Locked Out

Access Denied: Faulty Automated Background Checks Freeze Out Renters

Computer algorithms that scan everything from terror watch lists to eviction records spit out flawed tenant screening reports. And almost nobody is watching

The reports, sold as the most comprehensive picture of a housing applicant, contain a person’s criminal and housing records, which background check companies either buy from government agencies or data broker middlemen, or else scrape from free, public websites. While holding considerable influence over a person’s life, the criminal checks can be wildly inaccurate, as a recent joint investigation by The Markup and The New York Times found. But, perhaps even more common, they can be confusingly vague or unfairly include information from a person’s past that a court has deemed obsolete.

The Markup reviewed hundreds of federal lawsuits filed in the past 10 years against tenant screening companies and found dozens of accounts from people who alleged they’d been denied housing after tenant screening companies made mistakes in reporting their criminal records. Renters said the companies either relied on outdated or imprecise data, reported convictions that were expunged, reported arrests that didn’t lead to convictions, duplicated charges, mischaracterized misdemeanors as felonies, or presented mere traffic tickets as crimes. In a fast-paced housing market, these kinds of “zombie” records can make the difference between getting a home or being summarily dismissed.

“A lot of people who go through the criminal justice system, they don’t look at real time; what they’re really worried about is this mysterious criminal record that’s going to haunt them,” said Bart Kaspero, a defense attorney with an expertise in data privacy. “They don’t know what the hell it looks like, they don’t know where it’s going to creep up, or who’s going to see it.”

Why Old Data Won’t Die

RealPage, one leading tenant screening company, paid more than $1 million to settle a federal class action case in 2018 over its alleged practice of reporting information that had been expunged from the courts. The lead plaintiff in the case, Helen Stokes, alleged she had been rejected from two senior living centers because of two old arrests related to fights she had with her then-husband. Legally, the arrest records had been expunged and therefore didn’t exist; and yet, her suit claimed, they locked her out of housing.

“One of the biggest issues I see is the failure to update information as it becomes available, and in particular the failure to have procedures to make sure that expunged court files are being removed from their databases and not reporting those,” said Ryan Peterson, a tenant and consumer attorney in Minnesota who frequently litigates cases against background screening companies for inaccuracies in reports.

Using the right source for criminal background checks is also key, experts say.

26

Number of infractions incorrectly reported as felonies on one person’s screening report.

Data has a tendency to travel. When someone is arrested, indicted, prosecuted, tried, jailed, or put on probation, each agency at each step of the way creates its own records. Some are public, some are not. So, for instance, if someone has managed to expunge a criminal record from a court, the court may delete its record, but the jail where the person served their sentence might still retain the person’s jail record. That can cause some confusion.

Brian Miller was all ready to start fresh after he successfully petitioned to have three old felony convictions expunged from his criminal record. He had been convicted of the felonies in his 20s, and had spent 2005 to 2007 in an Arizona prison. Eleven years later, when he applied for a new apartment with his wife and daughter, they were dismayed to hear that not only were those three felonies showing up on his screening report, but also a shocking list of 26 more felonies.

Eventually Miller and his wife learned the source of those records: According to Miller’s ongoing lawsuit against the screening service On-Site (which is owned by RealPage), it had allegedly gotten his data not from the courts but from the state’s department of corrections, which has a free inmate lookup website. The so-called felonies were actually disciplinary infractions he had accrued in prison, according to Miller. As Miller alleged in a statement in his case against the company, “[O]ne item ‘sexual harassment’ was listed as a felony conviction on the Report, but was related to a time when I told a correction’s officer to kiss my posterior, and was written up for it.”

The decentralization of data across government agencies can also have a multiplying effect. According to cases filed against tenant screening companies in federal court, there are people who claim they have been denied housing because their screening reports made it look as if they had five different criminal convictions when a screening company mistakenly presented multiple court actions related to a single charge as different crimes. Others claim they have had probation violations connected to one criminal charge get counted as additional convictions too.

Minor Infractions, Major Headaches

In 2015, Ethan Harter was visiting Denver with his dad to look for apartments in anticipation of his cross-country move to begin law school. He filled out an application at an apartment he liked, paying the nonrefundable fee and checking “no” on all the boxes asking him if he had ever been convicted of or pleaded guilty to any felonies, sex-related crimes, or misdemeanor assaults. When he was rejected, he claimed in a lawsuit later filed against the screening company RealPage, the property manager told him that a criminal offense had shown up on his screening report.

The report showed a 2011 criminal offense from North Carolina, where he lived, but the specific charge was listed as “Not provided.” The property management company must have assumed he committed a serious crime, he thought.

It made my stomach turn.

Ethan Harter

The truth? It was a speeding ticket. Harter remembered being pulled over years before, on his way home from high school baseball practice. He had been going 75 in a 55-mph zone.

“It made my stomach turn,” Harter remembers now. “I was going into law school at the time, and I didn’t want people throwing around bogus information about me having a serious felony on my record.” Harter’s 2016 suit against RealPage for defamation and libel was ultimately dismissed after the judge decided that the screening report, while incomplete, was technically accurate.

Lashonda Whitehurst faced a similarly confusing situation when she was allegedly rejected from housing near Tampa, Fla., in 2018 because of a “misdemeanor” on her record from nine years earlier. When she finally tracked down a copy of her screening report from On-Site, according to a lawsuit she later filed against the company, she saw that the so-called misdemeanor was a reference to a fine she received from the county police when her burglar alarm had accidentally gone off.

Whitehurst sued On-Site for violating the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and her case was settled for an undisclosed amount in 2018.

Digital Punishment Can Perpetuate Inequality

These zombie records can sometimes follow people around for years, or even decades. Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, most negative information is supposed to drop off people’s consumer reports after seven years, but that rule doesn’t apply to criminal convictions.

Sarah Lageson, a sociologist at Rutgers University, has written about how the permanence of criminal records in the data economy amounts to a kind of “digital punishment” for everyone who’s ever had any encounter with law enforcement. When people have criminal records they can’t shake, their punishment by the state is extended by private companies that do background checks. Housing or job rejections can also make it harder for them to recover.

If you’re forcing people into unstable situations, the long-term consequences of that are more instability and more inequality.

Sarah Lageson, Rutgers University

“Any theory of rehabilitation, of making sure people can move on from past mistakes or move on from poverty, involves stability,” said Lageson. “If you’re forcing people into unstable situations, the long-term consequences of that are more instability, and more inequality.”

It’s also unclear that background reports, with all their flaws, actually help landlords choose the best possible tenants.

“There’s this overarching issue, which is, where’s the data that shows how predictive this information is?” asked Drew Sarrett, a consumer attorney in Richmond, Va. “Because if you deny someone, you can’t ever find it out. You’ll never know whether they would be a good tenant, because you won’t rent to them.”

A Unique, Simple Solution

There are states cracking down on zombie records, including Pennsylvania.

Back in 2008, the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts (AOPC) was getting multiple calls from people complaining that they had successfully gotten their criminal records expunged from the courts, but the records were still showing up on public websites, David Price, deputy chief counsel at AOPC, recalled on a webinar last year for others involved in reentry services.

He and his colleagues helped the callers get their expunged information taken offline, but they also wanted to figure out a way to make sure the court’s updated information was getting to the data brokers in a more systematic, proactive way.

So they came up with the “lifecycle file” in 2010: AOPC sells data brokers all of the state’s centralized court records and also sends out weekly updates to those records (like expungements) for free. The data brokers get direct access to the most accurate information, and in exchange they’re contractually required to incorporate those updates. AOPC even does random audits of the companies’ data to make sure they comply, and will cut off those that don’t.

Pennsylvania passed a “Clean Slate” law in 2018; since then, more than 35 million criminal cases have been automatically sealed from the public. But the AOPC’s system has been able to handle it.

There’s no magic here. We’d be happy to share our experience.

David Price, Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts

“In Pennsylvania, we’re really lucky—we actually don’t see a ton of errors with expunged or sealed cases coming up on private background checks, because of the lifecycle file,” said Seth Lyons, a supervising attorney at the nonprofit Community Legal Services of Philadelphia. “It successfully forces them to update their information.”

This lifecycle file system is possible in Pennsylvania because, compared to other states’, its data is already very centralized. But it doesn’t have to be the only place to try.

“Any court that’s interested in replicating this,” Price told his colleagues, “there’s no magic here; we’d be happy to share our experience.”