The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

This article is copublished with CalMatters, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. Sign up for its newsletters.

Last Saturday, I was at a community gathering of around 30 Vietnamese immigrants, all in their 50s and 60s, in Oakland, California, when I asked if anyone knew anything about AI or artificial intelligence.

None of them had ever heard of it.

In the past year, AI has become one of the most hyped technologies. Many have praised its potential to change knowledge work for the better, but even more people worry that the proliferation of easy-to-use AI tools could further pollute an already murky media ecosystem with even more false or misleading information.

And in this room full of elders from my community, the Vietnamese community, no one knew about it, which meant no one knew to look for it.

It was the third time I had visited this group to better understand how their lives were impacted by misinformation and how to give them the information they needed to navigate it. They were gathered in the morning, as they do every Saturday, to sing karaoke with their friends at the Vietnamese community center. But on this particular Saturday, I was also teaching them about deepfakes.

“Cái nào là mặt giả?” I asked.

“Which one is the fake face?”

Two Vietnamese Americans, Sarah Nguyễn, a PhD candidate at the University of Washington Information School studying misinformation in the Vietnamese community and Thảo Lê, a Vietnamese interpreter in training, were also present, to join and observe The Markup’s effort in educating the elders of my community about misinformation.

“Cái nào là mặt giả?” I asked again.

“Which one is the fake face?”

Several people squinted at the screen and started guessing letters. The room was very divided.

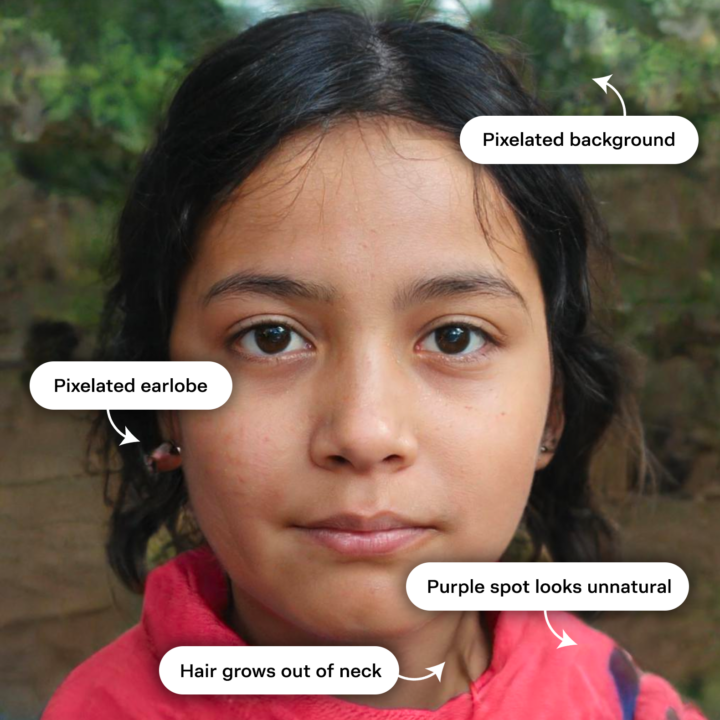

Now, my Vietnamese is good enough to get compliments from grocery store owners, especially when I make jokes or share my take on the best kind of banh mi. But it’s nowhere near good enough to speak about the minutiae of technology, let alone to describe the latest developments in AI. With the help of Lê and Nguyễn, who both chimed in whenever I was fishing for the Vietnamese translation of terms like “algorithms”, “automated recommendation systems”, and “fake news”, we revealed that the picture on the left was AI-generated.

Using a combination of hand waving, pointing, and a mix of Vietnamese and English, we pointed out details like:

“Tóc không bình thường.”

“Hair is not normal.”

“áo cũng không bình thường. Bên này khác bên này.”

“Clothes are not normal. This side is different from this side.”

What's wrong with this AI-generated photo?

This was our attempt to explain to these elders how AI is currently used. But despite their lack of knowledge of AI and various other technologies, these senior citizens are already struggling with online threats like robocalls or phishing attempts. One woman mentioned she was hacked on Facebook, while another man asked how he should respond to a robocall. “If I respond to the robocall’s question, does this mean they ‘got me?’,” asked one man. When we initially spoke to them, we also found that they were struggling to find good news sources in their language.

Hello World

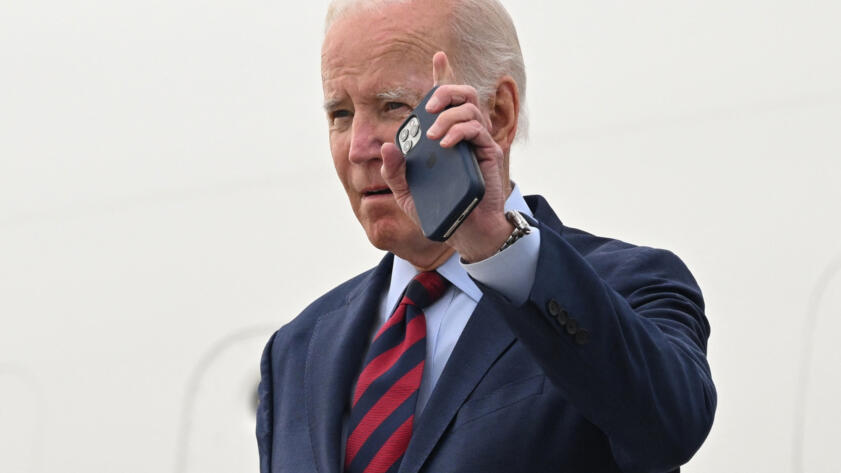

Deepfakes: Did Joe Biden Really Call?

A guide to spotting audio and video deepfakes from a professor who’s studied them for two decades

AI-generated calls may only complicate these issues. There have already been reports of AI-generated robocalls that were trained on the voices of loved ones and last year, mayor Eric Adams sent out AI-generated robocalls in Mandarin to New York City residents (he does not speak Mandarin).

But despite a year of headlines about AI, Nguyễn, Le and I were the first people to talk through concepts like algorithms and artificial intelligence with them.

It reminded me of the kind of role that children of immigrants generally play in families: we often become interpreters for our parents and grandparents, translating for them anything from important tax forms to cultural norms.

I grew up mostly speaking Vietnamese at home and I had only used it to ask for the foods I loved or to tell my parents about how school was going. Nguyễn and Lê had similar experiences.

So how did the three of us explain AI in Vietnamese?

“Nó giống như một cỗ máy. Nó học mặt của nhiều người xong nó làm mặt giả.”

“It’s like a machine that learned about many faces and then made a fake face.”