Subscribe to Hello World

Hello World is a weekly newsletter—delivered every Saturday morning—that goes deep into our original reporting and the questions we put to big thinkers in the field. Browse the archive here.

Hi everyone, Lam here.

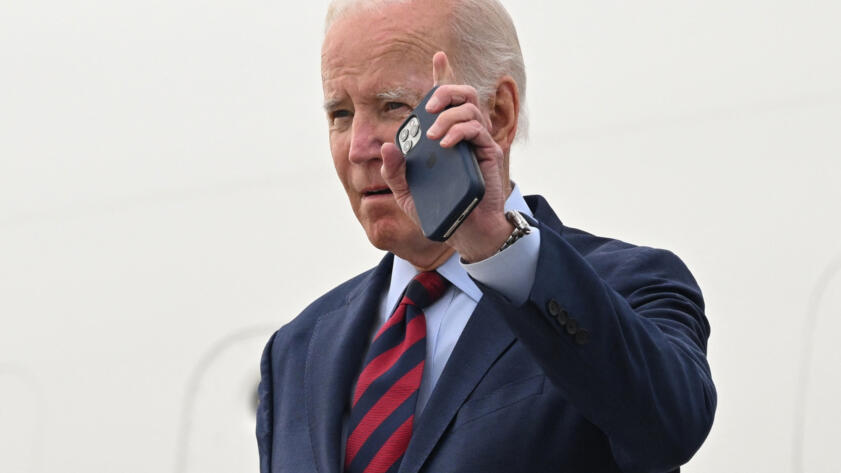

Earlier this year, there were reports of Joe Biden calling voters in New Hampshire to keep them from showing up at the polls during the primaries.

“It’s important that you save your vote for the November election,” President Biden said on the call, which emerged in the run-up to the state’s presidential primary in January. “Voting this Tuesday only enables the Republicans in their quest to elect Donald Trump again.”

Except, the voice that people were hearing on the other side wasn’t Biden. It was audio produced by generative AI, meant to deceive voters into thinking that if they vote during primary elections, they can’t vote during the general election. Biden’s fake robocall is just one of many recent examples of AI-generated content targeting U.S. voters.

This election cycle promises to be one that will likely continue to destabilize our sense of trust in public institutions. And while we may be worried about false actors using AI to confuse or dissuade voters, it’s increasingly being used to make political points: In March 2023, Republicans responded to Biden’s bid for reelection with a political ad, made with AI-generated images, that imagined a dystopian future if Biden were reelected. In June, Ron DeSantis’ campaign released an AI-generated fake video of Donald Trump hugging Anthony Fauci, the former chief medical adviser to the U.S. president who advised Trump during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, Trump recently claimed that an ad making him look bad was AI-generated, except the footage was real.

Deepfakes have arrived in the American mainstream in this election cycle and are blurring the line between fact and fiction.

I recently spoke with Siwei Lyu, a professor at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, about how anyone can try to spot deepfakes in 2024. He has studied deepfakes for more than two decades and is developing deepfake detection tools for the general public.

Fake Videos

Watch what is being said and how mouths move. Especially sounds that involve letters like B or P, you may notice that the lips are not closed when making those sounds, when they should be.

“If you look carefully at the words being spoken, and the movement of the lips, they may not be in perfect synchronization,” Lyu explained.

Fake Audio

Audio is more difficult to check. Our visual perception is usually better than our ability to catch clues that audio has been faked. That’s one reason fakers use Joe Biden’s voice to try and fool voters, instead of creating a video equivalent.

When trying to figure out if you’re listening to fake audio: First, listen for background noise. A lot of tools cannot reproduce ambient noise well. If someone is calling from outside and you don’t hear any background noise, that can sometimes be a giveaway.

Second, listen for a lack of “paralingual features.” These are the sounds we naturally make in between spoken words, like licking our lips or breathing. We’re so used to hearing them we barely notice they’re there, and right now, AI tools are bad at producing these kinds of sounds. But if you listen closely and a recording sounds a little too quiet, the audio might be AI-generated.

Using Common Sense

Even as technology improves and makes it harder for us to spot tells, Lyu said that the best defense is still common sense. It’s about being aware, slowing down, being proactive, and using a bit of fact checking, he said. If you get a call from someone claiming to be your relative but something sounds a little off, hang up and call that relative to check. If someone is calling to claim that you cannot vote, take the time to step back and research the issue a little bit.

Knowing that bad information and scammers are out there, especially the ones who want to take your money, it’s helpful to expect bad information from time to time and learn how to find the information you need.

Inside The Markup

Call for Pitches: Misinformation in Immigrant Communities

Help us expand our coverage of how misinformation impacts immigrant communities

Why are deepfakes becoming more and more common? In the past few years, deepfake technology has changed in a few major ways, according to Lyu. Technology has gotten a lot more sophisticated in producing content that sounds—and in the case of video, looks—more and more realistic. Who can access that technology has also changed. Three years ago, anyone who wanted to use generative AI to create deepfakes would have to know at least a little bit of programming. But since last year, more and more consumer-friendly software tools have lowered the barrier to entry.

I know that spotting deepfakes and other AI-generated information can feel like an endless game of Whac-a-Mole. But in my years of reporting on misinformation, one thing I’ve often seen is that polarizing and false information often takes advantage of people consuming information on the fly, such as when we’re reacting to breaking news (when information is still being gathered) or while we are passively doomscrolling through our social media feeds. As Lyu said, a helpful antidote to this is to slow down and to be proactive about your consumption of news and political information. This will mean researching organizations that serve you content and then building your own small but mighty trusted network of news and information—from local news outlets you like to institutions you regularly visit and trust, like your local library.

Thanks for reading,

Lam Thuy Vo

Investigative Reporter

The Markup