Hi,

I’m Aaron Sankin, a reporter here at The Markup. And I’m here to talk about how it’s kind of your fault that the internet sucks. But also it isn’t your fault at all, and you should probably be nicer to yourself about it.

Back in 2021, when Meta whistleblower Frances Haugen leaked a trove of the tech giant’s internal documents, much of the focus was on how the company’s products could be harmful to mental health—especially for young people. Instagram, the documents showed, had a tendency to make teen girls feel worse about their bodies. A 2018 shift in Facebook’s algorithm intended to strengthen social bonds instead stoked users’ rage. And an internal report found that one in eight users reported having an unhealthy relationship with the platform.

The reports sparked a public firestorm, not to mention congressional hearings, but for Whitney Phillips and Ryan Milner, Haugen’s smuggled documents confirmed what their years of research had already showed definitively: the online world can be a real drag.

Phillips and Milner—who teach media literacy at University of Oregon and College of Charleston, respectively—have spent their academic careers looking at toxic effects of online culture in books like The Ambivalent Internet and This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things. They began by looking at online enclaves infamous for digital pollution, like troll communities that delight in spreading toxic mischief far and wide. But they’ve come to see many of the bad feelings engendered by social media as algorithmically-intensified versions of the same set of anxieties that have plagued humanity since before two computers first traded data packets.

Everyone who uses the internet has, at some point, probably done something crummy and been the victim of someone else doing something crummy. It’s the circle of posts and it moves us all. But, luckily, interrupting this cycle is possible—if you use the internet a little more slowly, a little more mindfully.

Their 2023 book Share Better and Stress Less: A Guide to Thinking Ecologically About Social Media is an attempt to give readers, especially kids and teens, a framework for using the internet in a healthy and responsible way. What’s striking about the book is how nearly all of their suggestions are about what’s going on in your body rather than what’s going on in your computer.

I spoke with Phillips and Milner about how people can better regulate their emotions while scrolling, and to know when to pause, take a breath, and not get drawn into an online flame war that will only serve to make life worse for everyone involved.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Sankin: One of the things I liked about Share Better and Stress Less is that even though it’s framed in a simple and straightforward way that young people can understand, a lot of this advice is fairly universal for anyone trying to stay sane while using the internet. What prompted you to write the book?

Phillips: My own experience with this conversation about mental health and the role it plays in how we’re sharing and what our online spaces look like, a lot of that was really crystallized as COVID ramped up.

As that was happening, more of the conversations [among students in my media literacy class] were shifting to mental health. In part, because the world was getting increasingly more stressful, both politically and then also COVID. And that, of course, became political very quickly

In the classroom, the more I saw my students struggling, the more they were admitting to sharing in ways they recognized as being problematic. Students were starting to hear that maybe the university would be shut down. They’d be like, “All I’m doing is sharing rumors. I know most of them are probably false. I know that it’s probably bad that I’m doing it. But it makes me feel like I’m doing something and I cannot help it.”

They were trying to process information and hitting retweet, or whatever platform they were on, that was part of their process of coping.

Sankin: So much of the book is about regulating your own emotions, work that’s happening on this side of the screen, happening inside of your head. It’s thinking about your own relationship to social media as you are using social media and putting thoughtfulness into your moment-to-moment experience.

Phillips: A lot of that is not just your relationship to social media, it’s your relationship to yourself. How well are you able to identify what is happening in your body? People were not talking about embodied experiences when they were talking about the problem of mis- and dis-information. But those issues are intimately connected.

Hello World

Face Scanning and the Freedom to "Be Stupid In Public": A Conversation with Kashmir Hill

The longtime privacy journalist on how investigating Clearview AI helped her appreciate facial recognition—and envision a chaotic future

We all know what it feels like to be stressed out. That’s not something that’s talked about in a systematic way. This isn’t just about social media. This is about meat, our bones and our nervous system. Where has that been in this conversation about media literacy?

Milner: As we went along in our research, we started thinking and talking more about the cognitive and psychological elements. It was happening in our classroom conversations, for sure, but it was also happening in my own life.

During lockdown, when we were remote teaching, I would teach my couple classes in the morning and then during the afternoon, I wouldn’t have a ton to do. So I’d just melt into the couch and scroll through Twitter.

We use one example in the book of me scrolling through Twitter, seeing a video, overreacting to it, sending it to my brother, freaking out about it, and having to stop, fact check it, and then walk it all back. If, in the moment, I had stopped and said, “Where am I at? How am I doing? What am I doing? Is this the best for me right now?” If I would have had that moment of slowness and self-reflection, it would have done me a lot of good.

Sankin: Can you walk me through that feedback loop? Using the internet and coming across content that triggers you in a way that creates behaviors that, when you look back at them, you’re like, “I was not my best self in that moment.”

Phillips: I’m not a neuroscientist. So I’m not going to I’m not going to claim that level of expertise. But in reading and listening to people who are experts, a good way of looking at your brain is as a closed fist. The front part of your brain, the prefrontal cortex, is where all of your higher-level decision-making takes place. It’s what allows you to distinguish between real threats and imagined threats. Some scientists refer to it as the upstairs brain.

The downstairs part of the brain is where you have a lizard functioning. That’s the fight/flight/freeze, the limbic system. That’s what gets activated, what lights up when something overloads your system and you suddenly get overwhelmed, get scared, get angry.

The best way to think about it is that essentially you flip your lid—your prefrontal cortex becomes dislodged from the bottom part of your brain. You’re no longer able to do all of that really important higher-order functioning that that can help you identify, “that’s not actually a threat to me right now,” or “I can try to see where someone else is coming from,” or “I’m going to do something that’s going to help me take care of myself.”

All of those really important skills literally go offline. One of the things that activates the limbic system is when you get overwhelmed by too much information. Too much is coming at you. It’s too scary. It’s confusing. Once you lose that, the ability to have thoughtful communication goes out the door. Your ability to take care of yourself in appropriate ways goes out the door. Your ability to think about other people as people goes out the door.

All of those things are what push people into the screaming matches, to share things that under different circumstances when their lid was not flipped, they would maybe think twice about. We just don’t have the ability to be our most thoughtful, generous, flexible selves when we move into this space of stress.

Online spaces, because they’re designed to inundate us with information, are designed to inundate us with stress. Online spaces are just not conducive to this kind of thinking. That’s a problem because this kind of thinking is actually how we have important, difficult, challenging, thoughtful communication with other people. A lot goes wrong when you flip your lid and it just so happens the spaces we spend the most time in are designed to make it very difficult to keep your lid screwed on tight.

Hello World

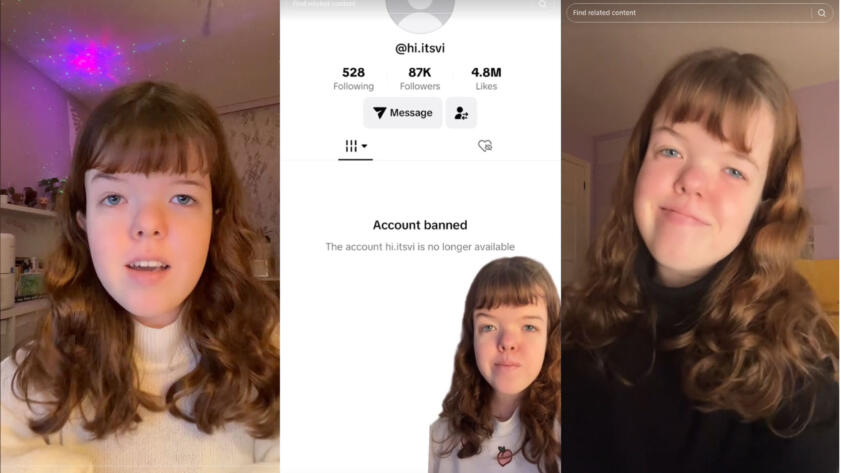

‘Every Day That I Don’t Get My TikTok Account Back Is An Opportunity That’s Lost’

How arbitrary account bans affect the livelihoods of creators with disabilities

Milner: When thinking of a younger audience, I think it’s even more of an important lesson, even more important to remember. Because, as we know, the upstairs brain isn’t fully developed. The prefrontal cortex isn’t as fully there. Young people in general are more inclined to shortsighted thinking, impulsiveness, and all the stereotypes about teenagers.

It really becomes this perfect storm where you have people who haven’t thought about the stuff as much yet, their brain isn’t quite there. And then you’ve got, like Whitney was just saying, an ecosystem designed to feed on those kinds of impulses.

Sankin: How would someone develop a practice that would allow them to disrupt this mechanism?

Phillips: These days, when I have conversations about technology, almost immediately, the conversation stops being about technology. A lot of what drives anxious behavior is fear of rejection. It’s feeling like you don’t have something that you need.

When people say, what should we do about these problems with technology? My short answer, and I’m not really being glib, is: everybody should be in therapy. But then, also recognizing that not everyone can go to therapy, not everyone has access to therapy.

But if you can’t, for whatever reason, how can you shift that relationship with yourself so that you are listening in a more compassionate way? Oftentimes when people get really frazzled and angry, they think what they’re feeling is anger and they’re actually wrong. It’s something else. It’s something that’s softer. We don’t always know how to talk to that part of ourselves and particularly how it manifests in our body.

The need for connection and the anxiety that emerges when we don’t get what we need as humans, as social beings. That isn’t new. That’s been around forever. But the technology has really shifted some of the dynamics and intensified a lot of the things that have already existed. they create more screens that people aren’t responding to us on.

I think it’s really important for people to think about some of the negative or potentially negative consequences of technologies. But also getting so focused on just the technologies themselves takes away both the embodied conversation and takes away from the fact that being a person is hard. It’s just really hard. Being an adult is really hard. Being a kid is really hard. We never fully figure things out. And every time we get a little older and get a little bit more mature, we realize other areas where there’s still a lot to learn.

Sankin: You make this argument in your book that everyone is in some way responsible for online pollution. If you exist online, you are going to do things from time to time that make the internet a slightly worse place. That really shifts the dynamic of the conversation, which I think is largely focused around the idea that the really toxic trolls, the apex predators of internet toxicity, are the problem.

Milner: The initial assumption that a lot of people would make going into a social media how-to guide for middle schoolers would be more about how to protect yourself from cyber bullies, from catfishes, from predators. How to put on your armor and put up your defenses. Ways that you can shelter yourself and insulate yourself from the big bad world out there.

But I think young people hear a lot of that and, in my experience having three kids, they get a lot of that. A lot of that is pretty intuitive after a little bit of conversation. When you’re gaming online, don’t give out your personal information. Don’t add random people on Snapchat.

The mentality is not one of pointing a finger, not one of saying “you’re messing this up” or “you’re doing this wrong” or “you’re being mean.” But instead, even if you think you’re right, think about the unintended consequences of being a person online.

We all know the story of how social media platforms get their money. The problem is that those ways to get money are very often directly at odds with what we need to be our best selves in these places. They’re at odds with being slow or being mindful. They reward that lizard brain sharing. They reward the anger. They reward the outrageous and sensational. There’s all kinds of tricks and schemes to get you to keep refreshing, keep scrolling.

The norms of social media now—the algorithmic docency, the slot machine dynamics, the reward for sharing and consuming outrage—none of those align well with the practices, mediated or otherwise, that get us to a less stressed kind of place.

Phillips: It’s important to get people to reflect on the less obvious parts of this conversation. If you’re approaching the issue as the problem online is people who intend to do harm. They’re setting out to cause harm. They are mean on purpose. If so, the solution to the problem is just don’t be mean, and that’s all you need to do.

If you shift how you are thinking to be about where polluted information, or problematic information, comes from, to think about the ways that we can potentially contribute to it, or that we’re just all part of this process, then nobody can step outside of the ecosystem, we’re all contributing something. That is an incentive to really take care of ourselves.

Especially aiming this message at younger people, God help them, they’re going to be inheriting this soon enough. And the question is what kinds of systems are they going to build? What kind of systems are they going to accept?

They won’t be able to know how to resist that or build something different if they don’t know what the problems are. You’ve got to have conversations about the individual and conversations about the collective, big and small, happening simultaneously to try to think about what kind of world could we build together.

Take a deep breath and check in with yourself,

Aaron Sankin

Investigative Reporter

The Markup