Warning: this methodology contains many offensive terms and expletives.

In 2007, only two years after YouTube’s launch, the Southern Poverty Law Center called it “the hottest new venue for extremist propaganda and recruitment.”

In the ensuing 14 years, journalists and researchers have continued to highlight YouTube’s effect on the propagation of the hate movement’s ideology, including The New York Times’ 2019 profile of a young man radicalized by what he saw on YouTube and a recent study showing that some of the platform’s users gradually migrated from moderate political content to fringe, racist videos.

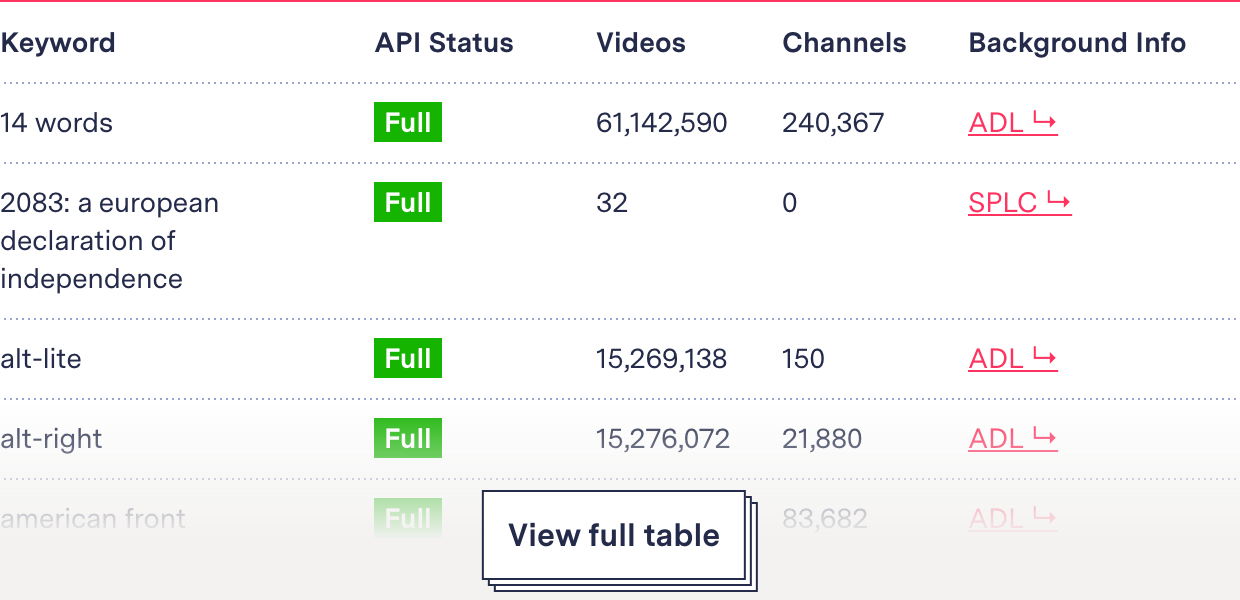

See our data here.

In recent years, advertisers have expressed concern about their ads appearing next to extremist content that could damage their companies’ reputations. In 2017, many major companies said they would halt advertising on YouTube due to hateful content on the platform. YouTube responded by introducing a new set of “brand safety” controls, including “removing ads more effectively from content that is attacking or harassing people based on their race, religion, gender or similar categories,” Google’s chief business officer, Philipp Schindler, said in a blog post.

The company says it prohibits “content promoting violence or hatred against individuals or groups,” based on attributes ranging from race and ethnicity to gender and sexual orientation, and Schindler promised to aggressively go after violators. Over a three-month period in 2019, YouTube said it removed more than 17,000 channels and 100,000 videos for violating its rules on hate.

Most of the advertisers that boycotted YouTube in 2017 came back, and its primary source of profit remains selling the attention of its billions of users. Advertising on YouTube earned parent company Google almost $20 billion in advertising revenue in 2019 alone.

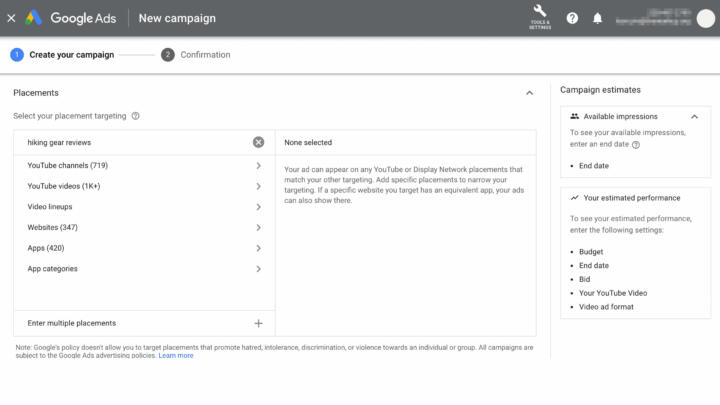

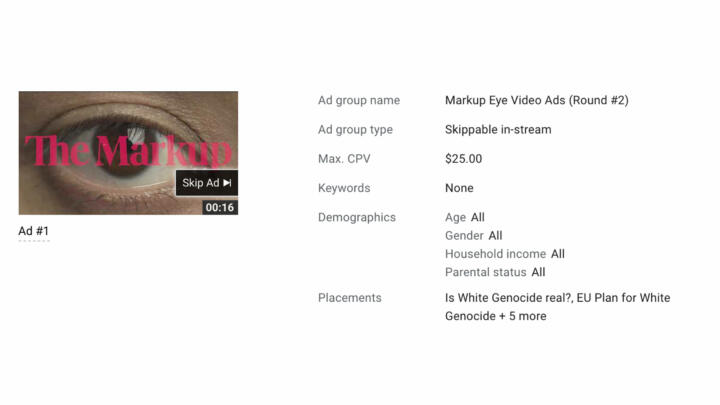

We sought to understand whether advertisers could use hate terms and phrases to target ads on YouTube, which would go against its public statement that hate speech is not “advertiser friendly.” Our goal was to examine whether the company was limiting or facilitating the placement of ads on hate content, rather than count up the number of hate-promoting videos that appear on the platform.

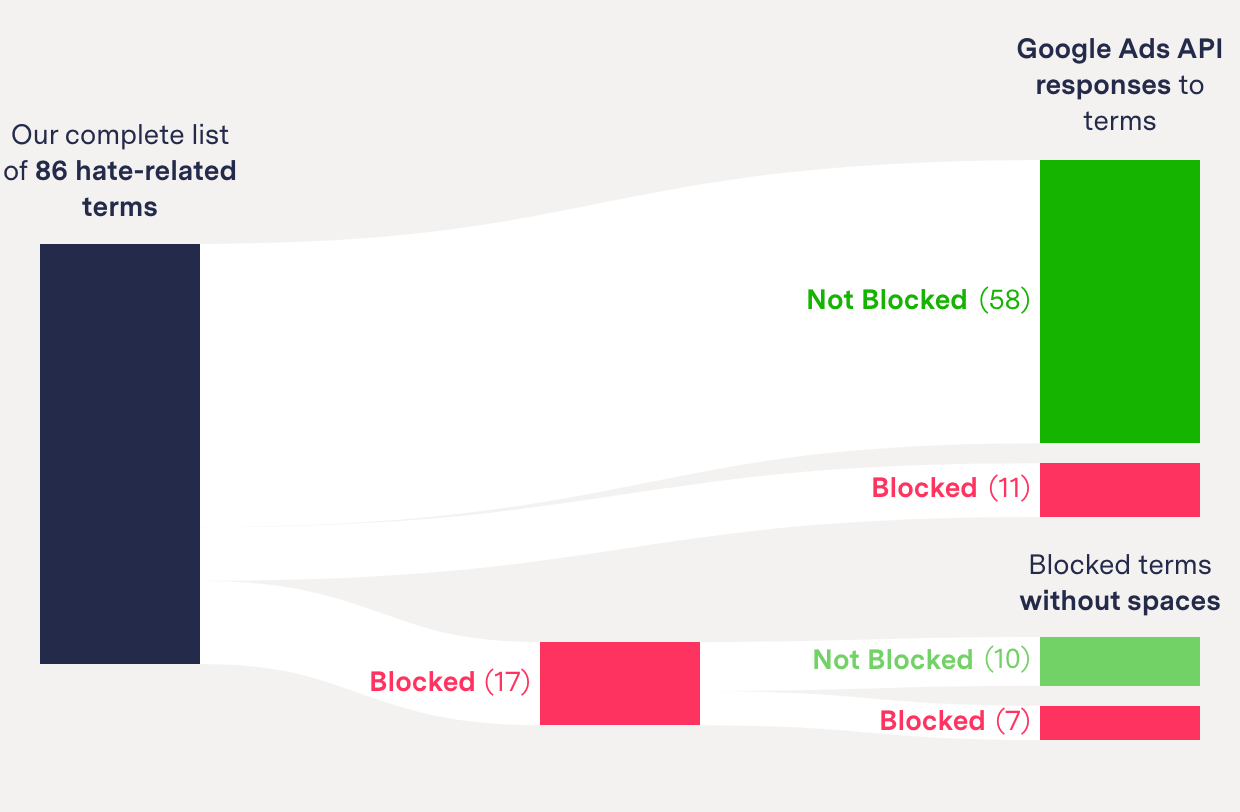

Using Google Ads, the portal allowing advertisers to place ads on YouTube, we found Google does in fact block some hate terms—but only a fraction of them, and in all but three cases, the blocks were easily circumvented.

Two-thirds of our list, 58 well-known hate terms and phrases, could be used to search for videos and channels upon which to place ads. Only a third of our list, 28 terms, were blocked. Removing spaces in multiword phrases or pluralizing singular nouns was enough to get around the block in almost every instance.

A video screencapture of the Google Ads Portal. It shows a user searching for ad placements on YouTube with the term 'white genocide'. Many videos and channels are suggested.

It’s not that YouTube lacks the ability to create stricter blocks but rather that it has chosen to be looser with some blocks, including for the terms “White genocide,” “heil Hitler,” and “gas the k—-” (we used the offensive racial epithet in our search, not dashes), which when run together without spaces could be used by advertisers to find videos. We found that the company has blocked other terms much more stringently. For instance, we found that any search containing “sex” or “Nazi,” even if it was a portion of the word, was blocked for ad placement.

Among the first 20 videos that appeared when searching for each of the hate terms and phrases were many news videos—which is consistent with YouTube’s prioritization of news media, which the company considers “authoritative.” But we also found some hate videos on the first tranche of 20 that appear on searches for hate terms on Google Ads.

Going deeper into the search results surfaced more troubling content, we found, including from dozens of channels identified by experts as “alt-right” or “alt-lite” and known peddlers of White supremacist, neo-Nazi, and other hateful talking points.

It’s impossible to know from the Google Ads portal whether the hate content it suggested for ad placements is “monetized”—meaning the videos can run ads and ad revenue is shared with whoever posted the videos. YouTube only discloses such revenue sharing to a video’s uploader, and the company places ads on videos even when it does not share revenue.

Google spokesperson Christopher Lawton said the company has a second tier of blocking that prohibits ads from running on certain offensive content, including “YouTube videos associated with the term ‘Whitegenocide’ and, therefore, no ads would have been allowed to appear alongside them.” He declined to say how many other words on our list received similar blocks or how those blocks were implemented. Other more mainstream videos that YouTube recommended for advertising related to “Whitegenocide” played ads as one of the authors of this article watched it.

In response to our findings and this methodology, the company expanded the number of hate terms on its blocklist. “Our teams have addressed the issue and blocked terms that violate our enforcement policies. We will continue to be vigilant in this regard,” Lawson said.

Even then, Google left 14 (16.3 percent) of the hate terms on our list available for ad placement searches, including the anti-Black meme “we wuz kangz,” the neo-Nazi appropriated symbol “black sun,” and “red ice tv,” a White nationalist media outlet that YouTube banned from its platform in 2019. When we asked Lawton why these hate terms remained available, he did not reply, but the company then took down 11 of them, leaving only three: the White nationalist slogan “you will not replace us,” “American Renaissance” (a publication described by the Anti-Defamation League as White supremacist), and the anti-Semitic meme “open borders for Israel.”

And Google’s new blocks did not follow the pattern of previous blocks, but rather the company replicated the API’s native response to words that return no relevant videos. The new blocked words now return the same response as gibberish in the API. In so doing, Google muddied any future efforts to replicate this investigation with other keywords, shielding the company from further scrutiny.

Methodology

Data Collection

Google Ads API for Ad Placements

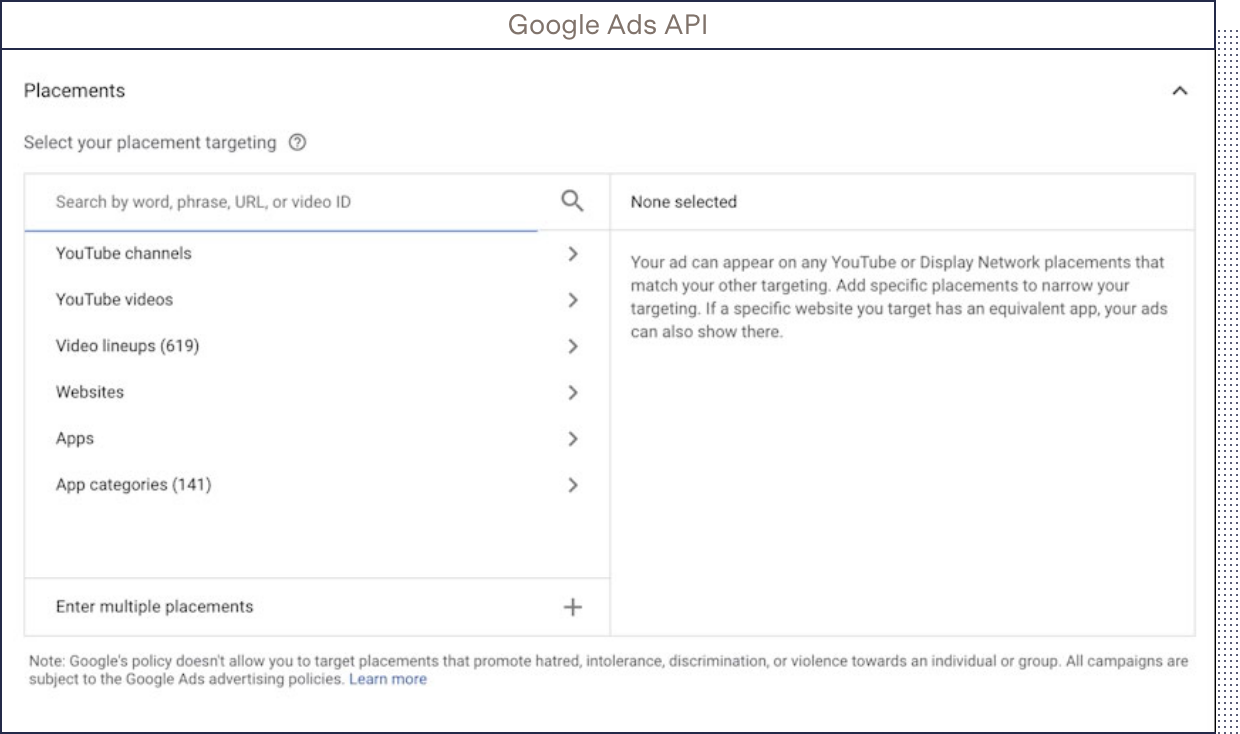

We set up an account on the Google Ads portal using the markup.org email address of one of the authors of this investigation. This is the portal where advertisers place campaigns on YouTube and other Google properties.

Our investigation focuses on one of the targeting options within the portal: ad “placements” on YouTube videos. This allows advertisers to use keyword searches to find and select specific videos and channels on which to advertise.

We discovered the portal’s undocumented API for ad placements (called “PlacementSuggestionService”) by manually typing keywords and listening for the portal’s network requests. This process allowed us to reverse-engineer the API for our investigation.

The API takes a two-letter country code; ours was “US.” This means this investigation only applies to the keyword blocklist for ad placements made in the United States.

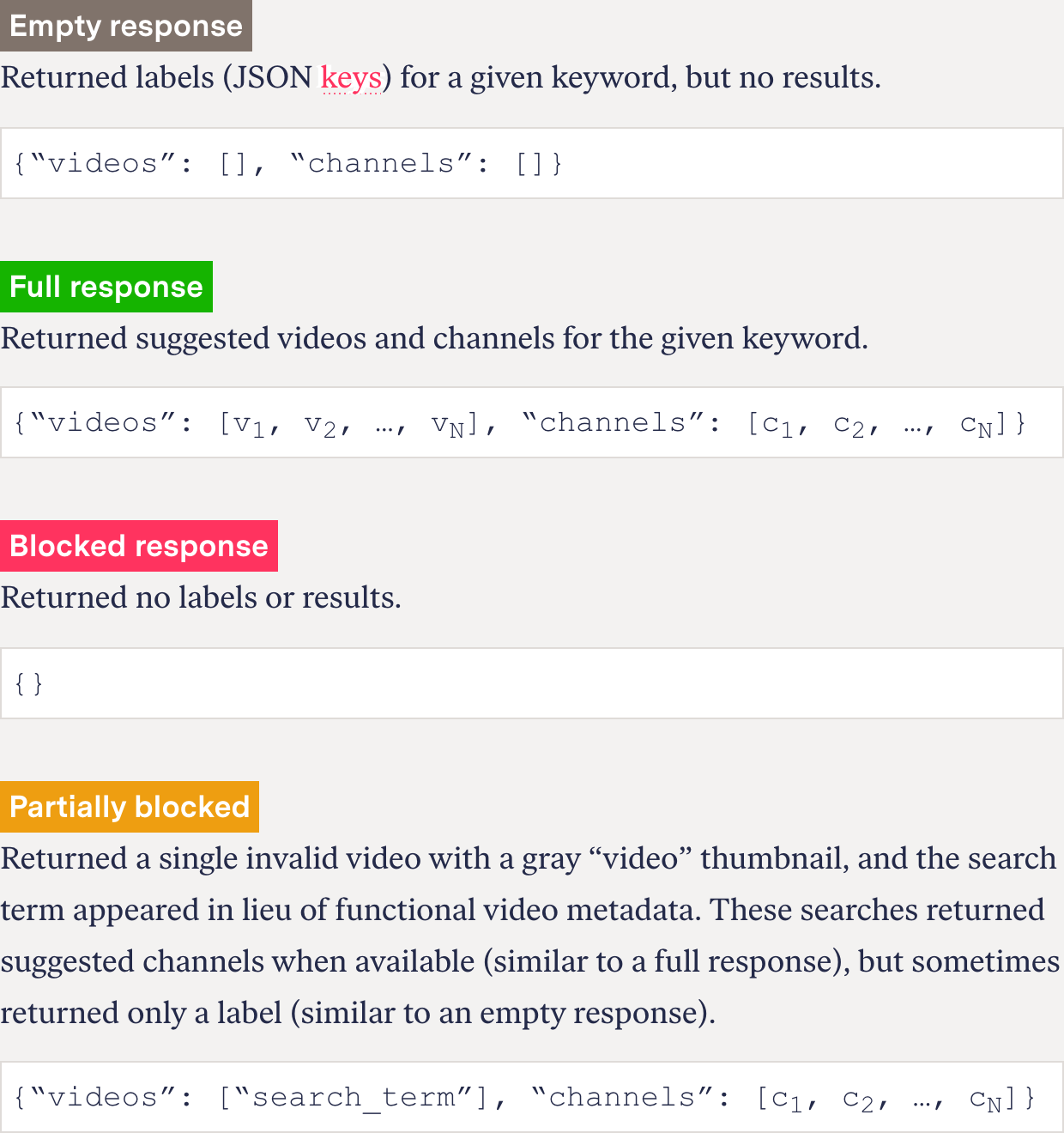

For any keyword, the API returned one of four kinds of responses, simplified below:

Empty response

Returned labels (JSON keys) for a given keyword, but no results.

{“videos”: [], “channels”: []}

Full response

Returned suggested videos and channels for the given keyword.

{“videos”: [v1, v2, …, vN], “channels”: [c1, c2, …, cN]}

Blocked response

Returned no labels or results.

{}

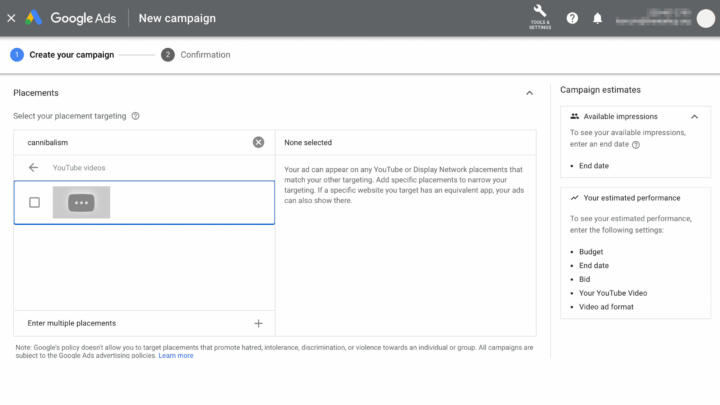

Partially blocked

Returned a single invalid video with a gray “video” thumbnail, and the search term appeared in lieu of functional video metadata. These searches returned suggested channels when available (similar to a full response), but sometimes returned only a label (similar to an empty response).

{“videos”: [“search_term”], “channels”: [c1, c2, …, cN]}

See the actual responses from the API in GitHub.

Full responses listed up to 20 suggested videos and 20 suggested channels and specified the total number of related YouTube videos and channels for the term. On the front end of the ad buying tool, the user can click to see more videos and channels, and the related videos list cuts off at “1K+.”

To understand the differences between searches that did not return a full slate of videos and channels, we did two things. First, we sent 20 random character strings as keywords through the API. These returned responses with labels but no videos or channels—what we called an “empty response” above. It is our marker for a term for which there are no actual related videos on the platform.

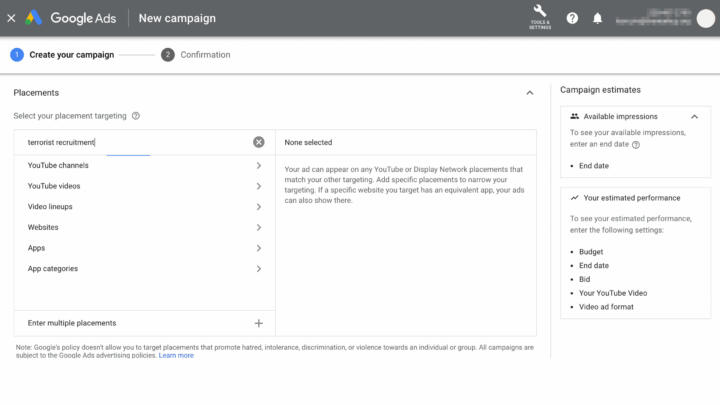

To determine whether and how the API blocked forbidden words, we created a list of 150 keywords from examples YouTube points to as violations in its community guidelines for video content. We sent these through the API, and the majority—75.3 percent—returned an empty JSON packet of data (“{}”). These are what we called “blocked” above. These blocked terms include “fuck,” “selling firearms,” and “terrorist recruitment.” (To see this list, and the API’s responses for each keyword, please refer to the “policy” tab in the “what_is_blocked.xlsx” spreadsheet in our GitHub.)

To an ad buyer, these blocked responses would look the same as an empty response, where there are truly no matching results on the platform: The portal shows no videos related to that keyword. It is only with access to the API that we are able to differentiate between a term that was blocked by the platform and one for which there are truly no responsive videos.

We didn’t get any empty responses from the API for any of the terms we searched. Each either surfaced videos or was fully or partially blocked.

Three prohibited terms, “cannibalism,” “dogfighting,” and “disparagement,” returned valid channel suggestions with an invalid suggested video—a gray thumbnail and the initial search term set as a video ID but no actual video. This is what we are calling “partially blocked” above. In our analysis, partially blocked search terms usually provided channel suggestions, but some terms did not, including “3Dprintguns.” We still consider those to be partially blocked due to the presence of the gray thumbnail video image.

Sourcing Hate Keywords

We created a list of 86 hate groups, slogans, conspiracy theories, and memes that are well-known or openly promote malice, hostility, or violence against one or more social groups. We kept it short deliberately. Using a larger list would have undoubtedly unearthed more terms on YouTube’s keyword blocklist but would have also inevitably led to contention about our choices, creating a distraction from our findings.

We began by gathering terms from three sources: the Southern Poverty Law Center (1,781 terms), the group Muslim Advocates (60 terms), and the Alt-right Glossary (198 terms) from RationalWiki.org, a nonprofit wiki centered on refuting pseudoscience and authoritarianism.

That produced a list of 2,039 terms, which we whittled down by removing names of individuals, local chapters of hate groups, obscure terms, and heavily coded dog whistles. We then ran that list through the Google Ads portal and removed keywords that did not return any hate-related YouTube videos in the top 20 results provided by the portal, in an abundance of caution.

We vetted this smaller list one more time, consulting media manipulation researchers at the Technology and Social Change project at the Shorenstein Center at Harvard University, and arrived at our final list of 86 vetted and active hate keywords. (Full list in “Findings” below.)

We ran the list of terms through the Google Ads API for ad placements on Nov. 20, 2020, and saved the JSON responses. We submitted each of the terms in multiple ways: as complete phrases, breaking them down into individual words, switching them from singular to plural, changing suffixes (‑ist became -ism), and removing spaces between multiple-word phrases.

Findings

What’s on the Blocklist

Of the 86 hate keywords on our list, 58 (67.4 percent) yielded full responses, with the portal listing suggested videos and channels for ad placements. These include “White power,” the White nationalist chant “blood and soil” (which echoed throughout the 2017 Unite The Right march in Charlottesville, Va.), and the White nationalist far right “great replacement” conspiracy theory. YouTube slaps a warning on videos about The Great Replacement and other “topics prone to misinformation” through an infobox that links to Wikipedia.

Only 28 hate terms on our list (32.6 percent) were blocked. These include “KKK,” “White pride,” and “White genocide,” a conspiracy theory about planned demographic shifts toward a White minority. YouTube puts a warning label on “White genocide” videos too.

None of the hate terms on our list returned partially blocked or empty responses. Each returned a full response or was blocked.

Band-Aid Fixes

To test the integrity of YouTube’s blocklist, we modified the terms that were blocked using rudimentary techniques to see if we could get around the ban. We were able to circumvent it in almost every case by using simple modifications such as removing spaces in multiword phrases or pluralizing singular nouns. This shows that the blocklists are a “Band-Aid” fix—small patches on larger problems.

When we removed spaces from the 17 multiword phrases that were blocked, most, 58.8 percent (10 terms), returned full responses and another 17.6 percent (three terms) returned partially blocked responses. Only one returned an empty response, similar to when we ran random strings of letters through the portal, and three queries continued to return blocked responses with spaces removed: “holocaustdenial,” “Whiteprideworldwide,” and “AmericanNaziparty.”

The base terms “Nazi,” “White pride,” and “holocaust” also returned blocked responses on their own. One oddity: “Whitepride” was not blocked without “worldwide.” (The list of blocked base terms is on GitHub.)

Space Removal Vulnerability

| Blocked response | Full response |

|---|---|

| white pride | whitepride |

| white pill | whitepill |

| white nationalist | whitenationalist |

| white genocide | whitegenocide |

| sieg heil | siegheil |

| radical islamic terror | radicalislamicterror |

| jewish question | jewishquestion |

| heil hitler | heilhitler |

| globalist jews | globalistjews |

| dual seedline | dualseedline |

We tested two other simple workarounds: swapping a singular with a plural noun (adding an “s”) and swapping suffixes (turning an “-ist” to an “-ism”). These workarounds also successfully circumvented the keyword block. While “White nationalist” was blocked, “white nationalism” returned a full response—as did the plural “White nationalists.” (We found this plural noun vulnerability when running banned phrases from YouTube’s policy list through the API as well. Notably, terms containing terrorist were banned, but not the plural terrorists.)

The plural noun vulnerability did not work for any of the single blocked words like “Nazi,” k—, or the n-word. (We used the actual offensive racial epithets in our search.)

The varying intensity of the blocks suggests that YouTube exercises an ability to be looser or stricter in its blocks, intentionally blocking some terms with a partial match and others only after an exact match.

The varying blocking levels we found could be the result of Google using regular expressions (or regex) to construct patterns to automate text matching. Regex can look for exact words or cast a wide net. For instance, regex can perform a partial match and find “Nazi” between characters or nestled in a sentence. Regex can also look for exact matches for phrases like “White nationalist.”

Hate Phrases vs. Hate Content

We analyzed a total of 1,311 unique videos from the top 20 suggestions from all the hate terms on our list. Most of these videos were from news outlets. CNN, AP Archive, PBS NewsHour, and VICE were among the most commonly suggested. YouTube says it surfaces “authoritative” sources higher than others in searches about “news, science and historical events,” which can explain why videos from established news organizations would regularly be among the first 20 results for many terms, even hate terms.

Importantly, Google Ads’ top suggestions also included videos by critics and debunkers of the hate movement, including Shaun and ContraPoints.

However, the portal’s top suggestions also included videos featuring the neo-Nazi podcast The Daily Shoah, White nationalist digital media outlet Red Ice TV, and the Council of Conservative Citizens, a White supremacist group that inspired a 2015 mass shooting at an African American church in Charleston, S.C.

Most common YouTube channels from video suggestions (top) and channel suggestions (bottom) for hate terms.

| YouTube channel | Video Suggestions |

|---|---|

| CNN | 27 |

| Ruptly | 24 |

| AP Archive | 18 |

| Destiny | 12 |

| The F/S Effect | 12 |

| Dystopia Now | 12 |

| Newsy | 11 |

| Global News | 10 |

| The Young Turks | 10 |

| Soap - Sim Racer | 9 |

| Journeyman Pictures | 8 |

| VICE News | 8 |

| NowThis News | 8 |

| YouTube channel | Channel suggestions |

|---|---|

| Democracy Now! | 4 |

| VICE | 4 |

| CinemaSins | 4 |

| PragerU | 4 |

| Beau of the Fifth Column | 4 |

| act.tv | 3 |

| Trae Crowder | 3 |

| StevenCrowder | 3 |

| The Officer Tatum | 3 |

| Pixel_Hipster | 3 |

| ContraPoints | 3 |

| Dia Beltran | 3 |

We cross-referenced the channels of all the uploaders of videos Google Ads recommended as the top 20 for each search term and compared them to channels that researchers at The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne identified as “Alt-right”—which the researchers defined as extremists who embrace White supremacist, anti-Semitic, and anti-feminist beliefs—and those the researchers identified as “Alt-lite,” who are almost identical but who deny embracing White supremacist ideologies “although they frequently flirt with concepts associated with it.”

We found 15 videos posted by seven “alt-right” channels and 18 videos posted by 15 “alt-lite” channels in Google Ads’ top tier recommendations for our search terms. We did not count the numerous re-postings by unofficial accounts of videos produced by banned (“deplatformed”) personalities including Stefan Molyneux, Mike Enoch, Alex Jones, and Ethan Ralph. As a result, this list is an undercount.

A more recent list created by researchers at Dartmouth College, Northeastern University, and University of Exeter and provided to The Markup by the Anti-Defamation League turned up 32 videos uploaded by 21 “extremist or white supremacist” channels and 53 videos uploaded by 41 “alternative” channels among Google Ads’ recommendations for the hate terms on our list. Because the ADL would not permit us to publish the names of those channels, we include this information for anecdotal purposes.

To find out what was deeper in YouTube’s catalog, we scrolled until we exhausted all available video suggestions from the ad portal on three hate keywords on our list: “Whitegenocide,” “we wuz kangz” and “White ethnostate.” We reviewed a total of 1,635 unique suggested videos and found that while news sources considered authoritative tended to dominate the first 20 results for each keyword, more fringe sources permeated later results.

For those three keywords alone, we found 14 videos uploaded from six channels identified by researchers as “alt-right” and 30 videos uploaded from 16 channels identified by researchers as “alt-lite.” (Again, for anecdotal purposes, the more-recent, private list provided by the ADL led to more matches: 23 videos uploaded from 14 “extremist” channels and 219 from 38 “alternative” channels.)

Among the videos suggested by Google Ads were dozens by demonetized Gamergate celebrity Carl Benjamin (“Sargon of Akkad”) alone, some of which include resurfaced messages from the neo-Nazi blog Stormfront. We also found racist propaganda that featured a West Virginia Attorney General’s office staff member reciting White nationalist mantras. The staff member was fired in 2016, after the original video was viewed more than 260,000 times.

This content analysis was done simply to find out if Google Ads would suggest any hate-promoting videos in response to the keyword searches or whether only news and other noncontroversial content would appear. We did not seek to document exactly how many hate-promoting YouTube videos or channels Google’s ad portal connects to the hate terms on our list. The API reported there are 169 million videos on YouTube related to the term “White power” that were available to advertise on, for instance, but we did not verify that the portal would load that many nor did we document all of them.

Limitations

Ad Blocking on Individual Videos

It is unclear what other blocks Google may implement to stop advertising on offensive content.

We attempted to place ads on videos that YouTube’s ad placements portal suggested for “Whitegenocide.” The seven videos we selected contained racist propaganda, White nationalist mantras, and far-right conspiracy theories. The ad campaign was greenlit as “eligible,” meaning it was “active and can show ads.”

Google spokesperson Christopher Lawton said in an email that the company has a second tier of blocking that prohibits ads from running on certain offensive content, including “YouTube videos associated with the term ‘whitegenocide’ and, therefore, no ads would have been allowed to appear alongside them.”

We received no such notification from Google Ads regarding our ad campaign, and Lawton declined to answer questions about why advertisers are not informed when the platform has decided a video is ineligible for ads. No ads were shown on our ad campaign before we ended it three days later, and our credit card was not charged.

Lawton also declined to answer questions about how many other words on our list received similar blocks or how they were implemented. Despite his statement that videos associated with the term “Whitegenocide” would be unable to play ads, other more mainstream videos that YouTube had recommended as related to that term played ads as one of the authors watched it.

For this reason, we do not know whether the YouTube videos Google Ads showed as related to the hate terms on our list could ultimately run ads.

He did say some of the videos we tried to advertise on have now been removed altogether for violating YouTube’s policies against hate.

Monetization

Our study did not seek to investigate whether YouTube allows those who produce hate videos to profit from them. There is no way to determine whether a video is “monetized” or not—meaning YouTube shares profits with whoever posted it—unless you own the video, or own copyrighted content featured in the video.

Further, YouTube’s recent change to its terms of service allows the company to advertise on “non-partnered” channels’ videos—meaning whoever posted the video may not be receiving any money from YouTube for ads that show up on it. Instead, YouTube keeps all profits for ads on such videos.

By the same token, just because a keyword is blocked from ad placements does not mean that all videos related to that keyword are demonetized, restricted, or subjected to any other form of penalty that YouTube takes against creators who break its rules.

For these reasons, we do not know if the videos and channels that YouTube suggested for ad placements on the hate terms on our list were monetized.

Google Response

Google spokesperson Christopher Lawton did not take issue with any of our findings or our methodology. He acknowledged that the company blocked some hate terms—and that many had slipped through.

“We take the issue of hate and harassment very seriously and condemn it in the strongest terms possible,” he said. “We fully acknowledge that the functionality for finding ad placements in Google Ads did not work as intended—these terms are offensive and harmful and should not have been searchable. Our teams have addressed the issue and blocked terms that violate our enforcement policies.”

We re-ran the list of hate terms through the API and found Google had blocked an additional 44 terms that had not been blocked before we approached the company.

Google responded to our study by blocking more terms

| Remained available | Newly blocked from placements |

|---|---|

| american renaissance | 14 words |

| amerimutt | 2083: a european declaration of independence |

| black sun | alt-lite |

| boogaloo | alt-right |

| color of crime | american front |

| diversity is a code word for anti-white | american identity movement |

| hammerskin | american vanguard |

| national socialism | blood and soil |

| open borders for israel | civilization jihad |

| race and iq | council of conservative citizens |

| red ice tv | cultural marxism |

| we wuz kangz | daily shoah |

| whitepill | daily stormer |

| you will not replace us | dualseedline |

| zionist occupation government | ecofascism |

| ethnic cleansing | |

| ethnonationalism | |

| ethnostate | |

| globalistjews | |

| great replacement | |

| heilhitler | |

| identitarianism | |

| identity evropa | |

| it's okay to be white | |

| jewishquestion | |

| league of the south | |

| lgbtp | |

| proud boys | |

| race realism | |

| race war | |

| racial holy war | |

| radicalislamicterror | |

| right wing death squads | |

| send them back | |

| shitskins | |

| siegheil | |

| sonnenrad | |

| southern nationalist | |

| swastika | |

| traditionalist worker party | |

| unite the right | |

| vdare | |

| war on whites | |

| white civil rights | |

| white ethnostate | |

| white lives matter | |

| white nationalism | |

| white power | |

| white separatism | |

| white sharia | |

| whitegenocide | |

| whitenationalist | |

| whitepride |

When we asked Lawton why the remaining 14 terms were still available for ad placements, he did not reply, but Google quietly took down all but three: the white nationalist slogan “you will not replace us,” “American Renaissance” (a publication described by the Anti-Defamation League as White supremacist), and the anti-Semitic meme “open borders for Israel.”

But the way Google took action effectively makes it impossible to replicate this investigation. For terms that originally returned full responses, the Google Ads portal now returns “empty” responses. This type of response had previously only appeared when we’d run strings of nonsensical letters through the platform and in one instance of a long hate phrase that we ran through without spaces. By returning empty responses for blocked words, too, Google has made it impossible to distinguish between the phrases the platform blocks and those for which there are no relevant YouTube videos.

The company did the same thing for nine of the 10 multiword phrases that had previously returned responses when we removed spaces—they now return empty responses. (“Whitepill” remains available for ad finding, despite being blocked as two words.)

Lawton declined to answer any of our specific questions about the portal or monetization, or whether the hate terms on our list were ever used to purchase advertisements.

Conclusion

We used two curated lists to reveal the existence of YouTube’s hate term blocklist, which was both brittle and alarmingly limited.

YouTube had blocked less than a third of the 86 hate terms on our list for ad placement searches. “White power,” “blood and soil,” and “great replacement” were among those that were cleared for ad placements. And all but three of the 17 blocked phrases could be circumvented with easy workarounds, like removing the spaces in multiword phrases or pluralizing singular nouns.

The varying strength of the blocks reveals that YouTube purposely made some more porous than others, limiting advertisers from ever searching for videos on permutations of the words “Nazi” or “KKK,” for instance, but allowing advertising on phrases such as “White genocide,” as long as they’re run together as one word.

Many of the videos Google Ads served up as potential advertisement for campaigns using the hate terms were from news channels—in fact, they tended to dominate the top 20 results. We also found some videos from critics and debunkers of the hate movement. However, we found dozens of videos posted by channels that experts label as “alt-right” or “alt-lite,” which they defined as flirting with but not publicly embracing White supremacist concepts.

When we brought our findings to Google, the company responded by blocking another 44 words and some additional phrases without spaces. But it left 14 (16.3 percent) of the hate terms available for video finding for ads, including the anti-Black meme “we wuz kangz,” the neo-Nazi appropriated symbol “black sun,” and “red ice tv,” a White nationalist media outlet that YouTube banned from its platform in 2019. When we asked why those were left, the company removed all but three of them.

Our discovery of YouTube’s keyword blocklist is the public’s first glimpse of YouTube’s effort to prevent advertisers from targeting potentially hateful content by blocking keyword searches.

While acknowledging the presence of its hate blocklist—and expanding it in response to our findings—Google also took steps to preclude future analysis by muddying this API’s responses to blocked phrases. It compromised the ad buying platform’s native response when there are no responsive videos for a word by sending the same signal for newly blocked words. This action serves only to further shroud the company’s actions in secrecy, shielding it from scrutiny by journalists, independent researchers, and others.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jeffrey Knockel of Citizen Lab, Robyn Caplan of Data & Society, and Manoel Ribeiro of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne for comments on an earlier draft of this methodology. We would also like to thank Brian Friedberg of the Technology and Social Change Project at the Shorenstein Center at Harvard University for reviewing the keyword lists used for our reporting.