In 2010, California hired the consulting firm Deloitte to overhaul the state website people use to apply for unemployment benefits. Things didn’t go well: Later that year, technical errors led to the halting of payments for some 300,000 people, according to the Los Angeles Times. And, the paper reported that, at $110 million, the final cost of the system was almost double the initial estimate.

A decade later, the taxed, aging system built by Deloitte in California is struggling again, this time under the strain of new applicants put out of work by the pandemic.

But Deloitte still won a fresh contract last month to again help out with California’s unemployment system. The Sacramento Bee reported that the company has received another $16 million to provide unemployment call center services and help deliver benefits. Deloitte still receives nearly $6 million per year under the contract to maintain the system, the Bee reported.

The move is part of a pattern: States continue to spend millions of dollars hiring Deloitte, IBM, and other contractors to build and fix unemployment websites, even amid growing concerns about the quality of their work. And the crush of unemployment applications flooding in around the country since the pandemic hit have only made the situation worse.

$77.9M

Total tab for Deloitte's 2013 contract with Florida to update its unemployment website. Errors prevented applicants from receiving crucial payments.

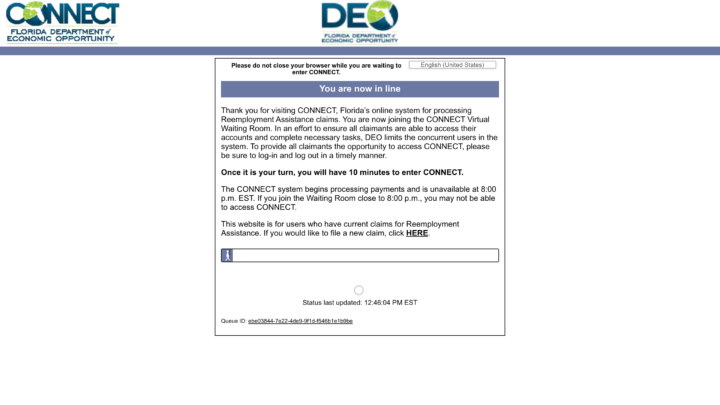

In Florida, the online unemployment system, also built by Deloitte, has crashed repeatedly, and phone help lines, staffed by the contractor Titan Technologies, have been continuously tied up. Nearly three million workers have filed claims, but the state has provided benefits to only about 1.6 million people, according to the Tampa Bay Times.

Problems struck Florida’s unemployment website almost immediately after Deloitte was hired to update the site in 2013 with a $63 million contract. Errors prevented applicants from receiving crucial payments, leading to a public battle between state officials and the company. The final tab for the site ballooned to almost $78 million.

The consulting company defended its performance at the time, saying it was continuing to improve the system and it would run more smoothly as employees from the Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO) learned to use it properly.

“As we have communicated to DEO, we believe that any remaining issues deemed ‘high impact’ by DEO’s own definition either require Departmental actions or are otherwise beyond Deloitte’s control,” they said.

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the site proved to still be fragile, leading to massive backups for claims. Florida governor Ron DeSantis recently described the overwhelmed system as “a jalopy in the Daytona 500” and ordered an investigation into how the state could have paid so much for so little.

Florida’s CONNECT unemployment system. The state paid Deloitte $78 million between 2013 and 2015 to overhaul the system. The company said it hasn’t worked on it in five years.

In a recent lawsuit, more than a dozen Florida workers accused state officials and Deloitte of negligence, arguing that problems with the application process have caused families to “lose homes, cars, savings, and dignity.”

Florida officials did not respond to a request for comment. Nor did state officials from California.

“Deloitte’s track record is just checkered with negligence—products that don’t work,” Gautier Kitchen, one of the attorneys representing the workers against the state and Deloitte, told The Markup. As cases have surged in the state, he said, he has heard from “droves” of workers still struggling to obtain benefits months later. The suit seeks class-action status.

Deloitte’s track record is just checkered with negligence—products that don’t work.

Gautier Kitchen, Florida attorney

A Deloitte spokesperson, Austin Price, said the company hadn’t worked on Florida’s system in five years and did not know “how, or even if, the technology has been maintained.” He said that, at the time Deloitte’s work ended, the system was “vastly outperforming the systems it replaced and processing claims more efficiently and accurately than ever before.”

Deloitte also faced blowback in 2013 for an unemployment benefits system it built in Massachusetts. There, the benefits system arrived in 2013, two years late and $6 million over budget—only to be filled with glitches that erroneously cut workers’ benefits, according to the Boston Globe.

Courtney Flaherty, a Deloitte spokeswoman, told the Globe the project had been complex and challenging, “and that is why we have invested considerable time and resources into making sure UI Online is a quality system that meets the needs of the Commonwealth and the people it serves.’’

Deloitte isn’t alone in its tumultuous history with benefits systems. IBM, another major player in the government IT industry, was awarded a $1.3 billion, 10-year contract to modernize Indiana’s welfare system in 2006. The state canceled the contract just three years later after complaints of erroneous benefits denials and other problems. Indiana and IBM sued each other over the dispute; the case has not yet been resolved.

Yet in 2010, IBM signed a $110 million deal with Pennsylvania to modernize its unemployment benefits system. The contract expired in 2013, ran millions over budget, and was never completed, according to a 2017 audit conducted by Pennsylvania auditor general Eugene DePasquale. In 2017, the state took legal action against IBM for breach of contract. That litigation is ongoing.

$1.3B

Value of 10-year contract IBM was awarded in 2006 to modernize Indiana's welfare system. The state canceled the contract just three years later.

“All told, Pennsylvania taxpayers paid IBM nearly $170 million for what was supposed to be a comprehensive, integrated, and modern system that it never got,” Gov. Tom Wolf said while announcing the lawsuit.

In statements, Deloitte and IBM both defended the work they’ve done on behalf of states.

Price also said the company had worked on systems in states including Minnesota and New Mexico, which he said have weathered problems relatively well. In California, the spokesperson added, Deloitte’s work has helped officials handle a swell of applications.

“Deloitte has successfully modernized labor and workforce systems in two dozen states and we are currently working with several states to implement new federal programs and scale their unemployment systems to respond to the unprecedented demand for benefits,” Price said.

IBM never delivered its planned Pennsylvania system, and company spokesperson Edward Barbini pointed out that the company had no hand in the current benefits system in Pennsylvania, which has also struggled to deliver payments to workers. The spokesperson added that the company had “invested significant resources” on a troubled welfare system in Indiana.

The pandemic has spurred problems beyond just a handful of states as more than 40 million workers have filed for unemployment benefits in recent months. Across the country, those workers say they’ve wrangled with outdated, complex systems that frequently fail, blocking them from obtaining benefits.

George Wentworth, senior counsel at the National Employment Law Project, said both vendors and states themselves likely share blame for breakdowns.

Some states, he said, have built systems with “a tremendous emphasis on fraud” that require complex work to determine who is eligible for benefits. In some cases, those decisions are too subjective to easily automate.

You’re dealing with state government and short memories.

George Wentworth, National Employment Law Project

“Some pieces of them are just more complex than the vendors anticipate,” he said.

When problems happen, he said, states often blame vendors for overpromising. Working with aging systems has exacerbated the challenges too.

“I think in general, you see these agencies think they can hand things over to the vendor and they’re going to just solve all their problems,” he said, “and you really need a high level of user competence and involvement from start to finish.”

Wentworth noted that changes in political administrations, as well as the emergency action required by the pandemic, mean some states may be willing to keep working with companies that have spurned them in the past. “You’re dealing with state government and short memories,” he said.

Regardless of the effectiveness of the work, the pandemic has likely set back any future modernization projects, as states shift their resources to handle the wave of applications and disperse aid dollars from the federal government.

“Anything that was going on before the pandemic hit—it’s going to be delayed indefinitely,” Wentworth said.

Update

This article was updated to add the name of the IBM spokesperson.