People dialing one of Florida’s call centers for help with unemployment claims in the past two months waited up to 12 hours to talk to an agent. On some days, up to 40 percent of callers simply gave up before receiving help. Millions more encountered a busy signal and hung up.

Those figures come from data provided to The Markup through a public records request to Florida’s Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO), which handles unemployment claims. The data, which is from April through early June, comes from Titan Technologies, one of several contractors the agency hired to help with the crush of workers struggling to file for unemployment over the past few months.

Titan is set to receive nearly $80 million for the work. The agency said it could not provide data from its other contractors.

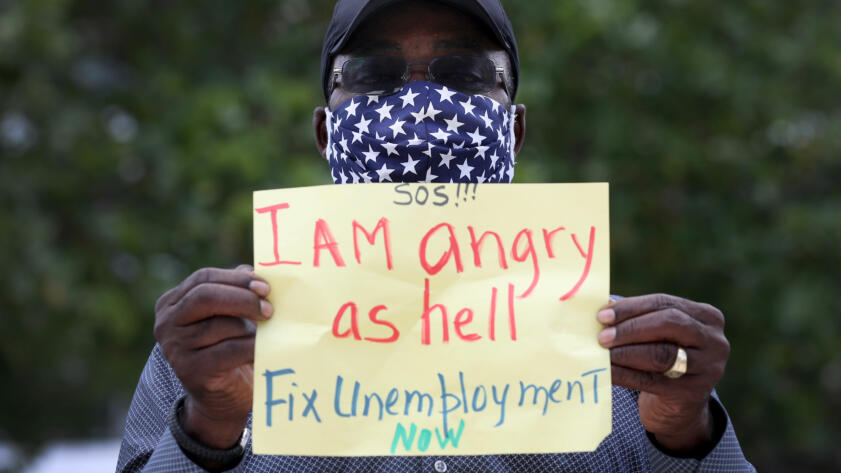

The data is limited, but it reinforces what workers all over the country have been saying since the COVID-19 pandemic and associated shutdowns hit: They’re struggling to navigate creaky government systems and access their unemployment benefits.

That’s been especially true in Florida, which, according to federal unemployment data, has been among the slowest states to process claims.

Early on, the state resorted to handing out paper unemployment applications, as people stood in line and risked contracting the coronavirus. One worker recently described seeking unemployment benefits as “at least a full-time job” in itself.

One Florida worker recently described seeking unemployment benefits as “at least a full-time job.

Daniel Rowinsky, a staff attorney at Legal Services of Greater Miami who represents low-income clients filing for unemployment, said the culprit is a technically flawed state system for filing claims that has consistently failed to properly calculate benefits.

About 80 percent of his clients, he estimates, have dealt with some sort of problem with their application that led to their not receiving money, or not being given the right amount. Those clients have needed manual assistance from the state to fix the errors, and that has contributed to the crowd of people filling up the phone lines.

“It appears that the only way to resolve the issues is a human being going into the system, figuring out the technical issue that is causing the problem with the claim, and then fixing it so that the person gets their money,” he said.

According to Paige Landrum, a spokesperson for Florida’s DEO, the agency has received nearly 20 million calls since March 15, with some weeks seeing hundreds of thousands of calls. Before Florida hired contractors like Titan Technologies in early April, the state reported it was able to answer only about 2 percent of its unemployment-related calls, and average wait times for help were 400 minutes.

The DEO now says wait times for specific problems are down to about 20 minutes. But since Titan Technologies started handling calls, workers have butted up against long wait times and frequent busy signals.

Between May 18 and June 8, agents with Titan Technologies answered almost 700,000 calls, according to the company’s data, but nearly 130,000 calls were abandoned. Additionally, during that time, nearly two million calls were “blocked” by the system, according to the data. The state’s contract with the company defines blocked calls as those that receive a busy signal and don’t reach an agent.

One Center Left 75% of Calls Unanswered

Calls monitored by Titan Technologies between May 18 and June 8

While the state eventually brought in thousands of new call center agents to handle the surge in unemployment, The Markup’s analysis shows Titan Technologies’ call center was understaffed early in the crisis.

At the beginning of April, as the pandemic swept the country and businesses were forced to close, the call center had about 80 agents assigned to unemployment-related queries. This appears to have been a major staff shortage. On April 6, callers hoping to ask about resetting the PINs for their online benefits waited an average of almost 3.5 hours before reaching an agent, and the 40 percent who abandoned their calls spent an average of nearly two hours waiting before hanging up. The longest wait time recorded that day was four seconds short of 12 hours.

In a statement, Landrum, from the DEO, said the agency “recognizes that many individuals are seeking an improved level of customer service that Floridians expect during this unprecedented time.” She said the agency has hired 6,000 customer service representatives to handle the flood, including the thousands used by Titan.

Elton Gumbel, a spokesperson for Titan, said in a statement that the company has “made great progress” since starting its work for the state in April, and that citing figures from the beginning of the contract period would “be an intentionally unfair representation of our efforts on behalf of the state of Florida.”

“No one could’ve predicted nearly 3 million Floridians would be unemployed essentially overnight, so early in our involvement of recruiting, hiring and training call takers, the wait times were erratic; however just as recently as last week the number of abandoned calls was less than 15%,” he said. “And as the process has continued to improve, the numbers have, too. As of June 16th, the average call wait time was just 31 minutes.”

As recently as last month, more than 2,000 agents were assigned to handle calls on some days, compared to less than 1,000 for much of April. In April and May, the percentage of calls eventually handled by a representative reached as high as 98 percent, but that number was also erratic: Other days it fell to around 70 percent, meaning thousands of calls were abandoned.

It doesn’t surprise me when people abandon calls.

Julia Simon-Mishel, Philadelphia Legal Assistance

“It doesn’t surprise me when people abandon calls,” said Julia Simon-Mishel, supervising attorney of the Unemployment Compensation Unit at Philadelphia Legal Assistance, who studies unemployment systems nationally. “If you’re on wait for four hours, and let’s say your kids start screaming, or a food delivery arrives, or a job calls you back on an application—there’s all sorts of things when you would have to then hang up the phone,” she said.

The Florida data provided to The Markup, because it represents services from only one call center company, is incomplete. On one day last month, the state’s unemployment agency said publicly that it received one million calls, but the most calls logged on a single day in the data on the Titan Technologies center was about 228,000, and of those, about 185,000 were blocked by the system, according to the data.

Some information is also missing from the documents for unclear reasons: Figures on some of the longest wait times and average time before abandoning a call aren’t included for parts of April, and different categories of data are logged for different months.

But the data does give a glimpse into the dire situation for workers looking for help with their claims.

It also raises questions about how the state chose to allocate its resources during the pandemic. Titan Technologies’ contract includes fielding calls about unemployment claims, like resetting PINs, or for more general assistance. But the company was also paid to take calls reporting alleged unemployment fraud. This was the least common reason for calling, according to the data, but still required the center to field hundreds of more calls on some days. Rowinsky, the Miami Legal Services attorney, said it was “absurd” to allocate resources to that option while so many struggled with applying for benefits.

Florida hasn’t been alone in facing technical problems with its unemployment benefits system. The pandemic-fueled unemployment crisis has exposed the cracks in several states’ systems, as workers report struggling for weeks, or even months, to receive benefits.

Unemployed workers blame errors and unintuitive systems for stymieing their applications. The problems could force a reckoning over how governments design systems that unemployed workers must navigate.

In the meantime, many applicants are still calling the state, and its contractors, for help—and many aren’t getting it.

Rowinsky said he was working with people struggling through the application system while unsure if they’d be able to make rent. “When I think in terms of the claimants, the clients,” he said, “it’s a nightmare.”