States around the country are dealing with the economic fallout of the coronavirus, as businesses shutter and unemployment claims hit unprecedented levels. With 3.3 million new unemployment claims in one week alone, the digital systems meant to provide benefits to workers are showing signs of strain.

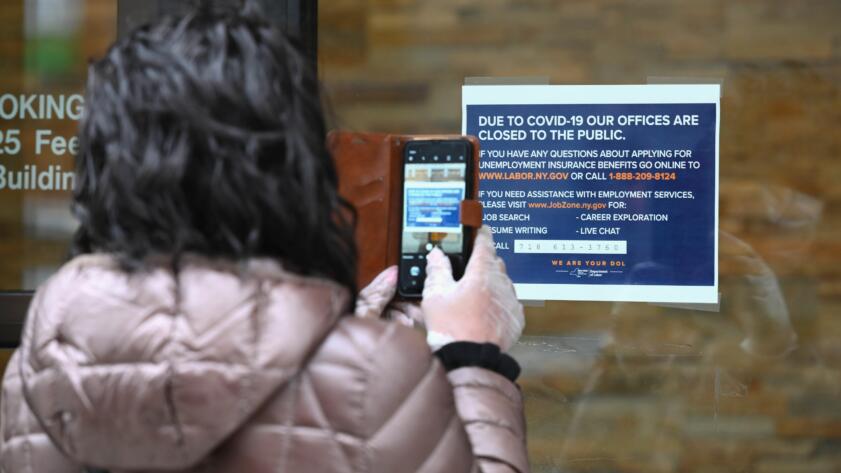

In several states—including Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, and Hawaii—online benefits systems have buckled under the crush of new applicants. Advocates, meanwhile, say the coronavirus has closed public spaces like libraries, whose computers people used to use to file for benefits, eroding access to a crucial lifeline even further.

Signing up for those benefits is especially important now. Under a federal relief package, workers receiving unemployment in their state will be eligible for an additional $600 per week in compensation, and the legislation will extend the time workers receive benefits by at least 13 weeks.

“Everyone’s scrambling and trying to figure out what systems they can key into to provide some level of support in what is proving to be a rather traumatic time,” said Julia Simon-Mishel, supervising attorney of the unemployment compensation unit at Philadelphia Legal Assistance.

The exact requirements that workers must meet to receive unemployment insurance benefits vary by state, but generally, workers who’ve lost their job through no fault of their own are eligible to apply with their state government for the benefits, so long as those workers meet their state’s requirements for wages earned or time spent in a lost job. Jobless workers file claims by providing personal and financial information either in person, by phone, or through a website.

In Pennsylvania, Simon-Mishel said, there are three options for applying: filing by paper—a generally unpopular option—or applying over the phone or through an online system. The phone system was overloaded even before now, Simon-Mishel said. “Unfortunately Pennsylvania, like other states, for the last several years has struggled off and on with busy signals and long wait times on their phone lines,” she said.

The online application system in the state, meanwhile, can be detailed and cumbersome, depending on your circumstances, according to Simon-Mishel. In other words, it can be difficult to put together on a mobile device—which is all some have access to while the virus puts public spaces on lockdown. “A lot of people who would normally go find a computer at a library or at a workforce center, they’re currently unable to go out and go to those places, or those places are closed,” Simon-Mishel said. The web interface, she said, is “not very mobile-responsive.”

In Massachusetts, a similar story has been unfolding. Greater Boston Legal Services consulting attorney Monica Halas told The Markup that new applicants have also swamped the system, leading the website to display a message offering to call back applicants by phone.

While state workers have done their best to process applications, Halas said, the online system has “never worked well,” requiring applicants to navigate difficult terms and design choices. The state has been planning to overhaul the system but hadn’t accomplished it yet.

Similar anecdotes have also appeared in news reports around the country. In Michigan, Steve Gray, the director of the state’s unemployment insurance agency, told local reporters “an unprecedented number of calls and clicks has challenged the system, particularly during peak hours,” but it was doing its best to handle the surge. Some pages on the online form were taking several minutes to load, according to the agency.

In Colorado, applications rose nearly 1,500 percent in a week this month, leading to days of crashes and error messages, according to the Denver Post. Hawaii was forced to replace its online application portal with a new form after repeated crashes, according to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser. “We’re living in uncertain times,” the director of the state’s department of labor relations, Scott Murakami, told the paper. “We’ve never seen this level of unemployment claims.”

A spokesperson for the labor department in New York, the epicenter of the American COVID-19 crisis, told The New York Times that unemployment claims had hit “a spike in volume that is comparable to post 9/11.”

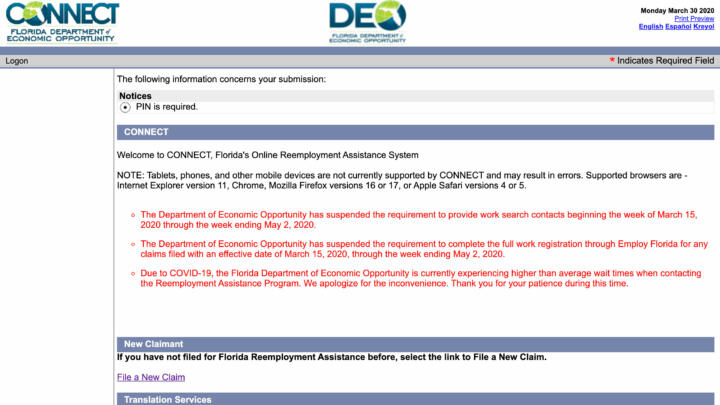

Even in the best of economic climates, filing for unemployment benefits can be onerous, especially for those without computer skills or easy access to a computer or broadband internet. A 2015 report on Florida’s unemployment insurance system from the National Employment Law Project found that thousands of unemployed workers in the state were denied benefits because of technical issues with an online platform the state mandated be used. Another set of online errors later caused monthslong delays in receiving benefits, and according to the report, fewer than one in eight jobless workers were receiving benefits in the state by 2015.

Daniel Rowinsky, a staff attorney at Legal Services of Greater Miami, said Florida’s design of the system has “marginally improved” over the years but that it was still not ready for the recent applications. He said he was repeatedly kicked out of the state’s website while trying to help a client.

He said the state should have learned from Hurricane Irma in 2017, when new users caused similar problems with overload. “It appears that they were not really prepared for this, which is shocking to me, given our experience with Irma,” Rowinsky said.

Unemployment benefits have been getting harder to obtain, advocates say. In 2017, the National Employment Law Project found that the percentage of jobless workers receiving unemployment insurance had declined 25 percent since before the 2008 economic recession. The study found that many states were purposely restricting eligibility, making it harder to get approved or to appeal and cutting the length of time people could get benefits.

The move to online only exacerbated the problem, the study found. In many states, the difficult-to-complete online application systems were responsible in large part for the decline. The report concluded that these changes could “leave U.S. families and the national economy more vulnerable than ever before to the next serious recession.”

That recession now appears to be here, as the coronavirus sends the economy into a rapid, unexpected tailspin and workers seek aid. “It is so much harder for everybody than a recession or a depression because of the isolation,” said Halas, the Boston legal services attorney. “People don’t have support, and they don’t have other avenues of access. You can’t walk in in-person anymore. It’s terrible.”