In early November, Facebook published its Q3 Widely Viewed Content Report, the second in a series meant to rebut critics who said that its algorithms were boosting extremist and sensational content. The report declared that, among other things, the most popular informational content on Facebook came from sources like UNICEF, ABC News, or the CDC.

See our data here.

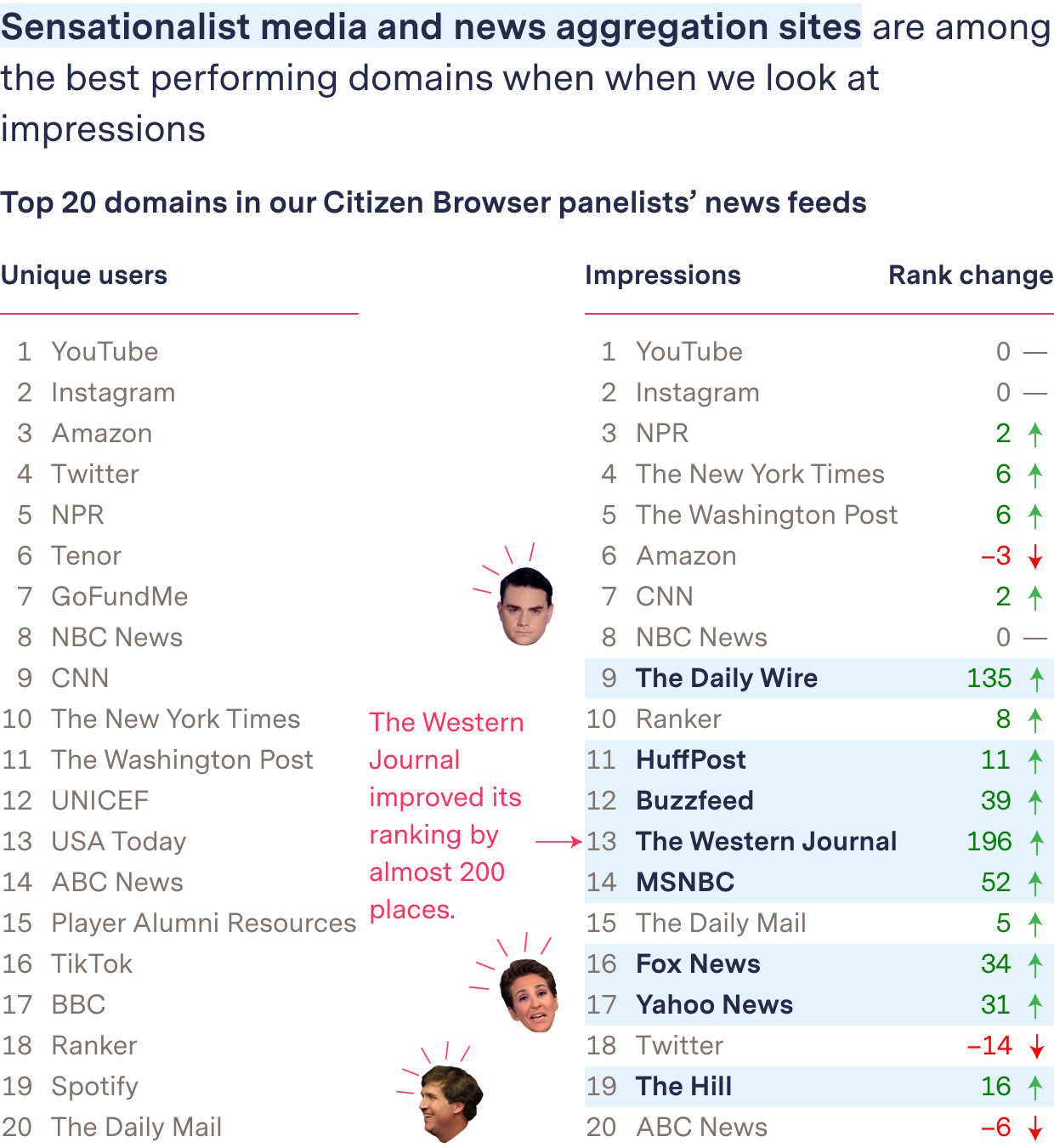

But data collected by The Markup suggests that, on the contrary, sensationalist news or viral content with little original reporting performs just as well as—and often better than—many mainstream sources when it comes to how often it’s seen by platform users.

Data from The Markup’s Citizen Browser project shows that during the period from July 1 to Sept. 30, 2021, outlets like The Daily Wire, The Western Journal, and BuzzFeed’s viral content arm were among the top-viewed domains in our sample.

Show Your WorkCitizen Browser

How We Investigated Facebook’s Most Popular Content

We found that Facebook's popularity metric obscures how well ultra-conservative content does on the platform

Citizen Browser is a national panel of paid Facebook users who automatically share their news feed data with The Markup.

To analyze the websites whose content performs the best on Facebook, we counted the total number of times that links from any domain appeared in our panelists’ news feeds—a metric known as “impressions”—over a three-month period (the same time covered by Facebook’s Q3 Widely Viewed Content Report). Facebook, by contrast, chose a different metric, calculating the “most-viewed” domains by tallying only the number of users who saw links, regardless of whether each user saw a link once or hundreds of times.

By our calculation, the top performing domains were those that surfaced in users’ feeds over and over—including some highly partisan, polarizing sites that effectively bombarded some Facebook users with content.

Sensationalist media and news aggregation sites are among the best performing domains when when we look at impressions

Top 20 domains in our Citizen Browser panelists’ news feeds

Unique users

| 1 | YouTube |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Amazon |

| 4 | |

| 5 | NPR |

| 6 | Tenor |

| 7 | GoFundMe |

| 8 | NBC News |

| 9 | CNN |

| 10 | The New York Times |

| 11 | The Washington Post |

| 12 | UNICEF |

| 13 | USA Today |

| 14 | ABC News |

| 15 | Player Alumni Resources |

| 16 | TikTok |

| 17 | BBC |

| 18 | Ranker |

| 19 | Spotify |

| 20 | The Daily Mail |

The Western Journal improved its ranking by almost 200 places.

Impressions

Rank change

| 1 | YouTube | 0  |

| 2 | 0  |

|

| 3 | NPR | 2  |

| 4 | The New York Times | 6  |

| 5 | The Washington Post | 6  |

| 6 | Amazon | –3  |

| 7 | CNN | 2  |

| 8 | NBC News | 0  |

| 9 | The Daily Wire | 135  |

| 10 | Ranker | 8  |

| 11 | HuffPost | 11  |

| 12 | Buzzfeed | 39  |

| 13 | The Western Journal | 196  |

| 14 | MSNBC | 52  |

| 15 | The Daily Mail | 5  |

| 16 | Fox News | 34  |

| 17 | Yahoo News | 31  |

| 18 | –14  |

|

| 19 | The Hill | 16  |

| 20 | ABC News | –6  |

These findings chime with recent revelations from Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, who has repeatedly said the company has a tendency to cherry-pick statistics to release to the press and the public.

“They are very good at dancing with data,” Haugen told British lawmakers during a European tour.

When presented with The Markup’s findings and asked whether its own report’s statistics might be misleading or incomplete, Ariana Anthony, a spokesperson for Meta, Facebook’s parent company, said in an emailed statement, “The focus of the Widely Viewed Content Report is to show the content that is seen by the most people on Facebook, not the content that is posted most frequently. That said, we will continue to refine and improve these reports as we engage with academics, civil society groups, and researchers to identify the parts of these reports they find most valuable, which metrics need more context, and how we can best support greater understanding of content distribution on Facebook moving forward.”

Anthony did not directly respond to questions from The Markup on whether the company would release data on the total number of link views or the content that was seen most frequently on the platform.

The Battle Over Data

There are many ways to measure popularity on Facebook, and each tells a different story about the platform and what kind of content its algorithms favor.

For years, the startup CrowdTangle’s “engagement” metric—essentially measuring a combination of how many likes, comments, and other interactions any domain’s posts garner—has been the most publicly visible way of measuring popularity. Facebook bought CrowdTangle in 2016 and, according to reporting in The New York Times, has since largely tried to downplay data showing that ultra-conservative commentators like The Daily Wire’s Ben Shapiro produce the most engaged-with content on the platform.

Shortly after the end of the second quarter of this year, Facebook came out with its first transparency report, framed in the introduction as a way to “provide clarity” on “the most-viewed domains, links, Pages and posts on the platform during the quarter.” (More accurately, the Q2 report was the first publicly released transparency report, after a Q1 report was, The New York Times reported, suppressed for making the company look bad and only released later after details emerged.)

1,065

Number of times articles from Newsmax appeared in one Citizen Browser panelist's news feed from July through September of this year.

Source: The Markup Citizen Browser

For the Q2 and Q3 reports, Facebook turned to a specific metric, known as “reach,” to quantify most-viewed domains. For any given domain, say youtube.com or twitter.com, reach represents the number of unique Facebook accounts that had at least one post containing a link to a tweet or a YouTube video in their news feeds during the quarter. On that basis, Facebook found that those domains, and other mainstream staples like Amazon, Spotify, and TikTok, had wide reach.

When applying this metric, The Markup found similar results in our Citizen Browser data, as detailed in depth in our methodology. But this calculation ignores a reality for a lot of Facebook users: bombardment with content from the same site.

Citizen Browser data shows, for instance, that from July through September of this year, articles from far-right news site Newsmax appeared in the feed of a 58-year-old woman in New Mexico 1,065 times—but under Facebook’s calculation of reach, this would count as one single unit. Similarly, a 37-year-old man in New Hampshire was shown 245 unique links to satirical posts from The Onion, which appeared in his feed more than 500 times—but again, he would have been counted just once by Facebook’s method.

When The Markup instead counted each appearance of a domain on a user’s feed during Q3—e.g., Newsmax as 1,065 instead of 1—we found that polarizing, partisan content jumped in the performance rankings. Indeed, the same trend is true of the domains in Facebook’s Q2 report, for which analysis can be found in our data repository on GitHub.

We found that outlets like The Daily Wire, BuzzFeed’s viral content arm, Fox News, and Yahoo News jumped in the popularity rankings when we used the impressions metric. Most striking, The Western Journal—which, similarly to The Daily Wire, does little original reporting and instead repackages stories to fit with right-wing narratives—improved its ranking by almost 200 places.

Was Facebook’s research genuine, or was it part of an attempt to change the narrative around top 10 lists that were previously put out?

Jane Lytvynenko, Harvard Kennedy School Shorenstein Center

“To me these findings raise a number of questions,” said Jane Lytvynenko, senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School Shorenstein Center.

“Was Facebook’s research genuine, or was it part of an attempt to change the narrative around top 10 lists that were previously put out? It matters a lot whether a person sees a link one time or if they see it 20 times, and to not account for that in a report, to me, is misleading,” Lytvynenko said.

Using a narrow range of data to gauge popularity is suspect, said Alixandra Barasch, associate professor of marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business.

“It just goes against everything we teach and know about advertising to focus on one [metric] rather than the other,” she said.

In fact, when it comes to the core business model of selling space to advertisers, Facebook encourages them to consider yet another metric, “frequency”—how many times to show a post to each user on average—when trying to optimize brand messaging.

Data from Citizen Browser shows that domains seen with high frequency in the Facebook news feed are mostly news domains, since news websites tend to publish multiple articles over the course of a day or week. But Facebook’s own content report does not take this data into account.

“[This] clarifies the point that what we need is independent access for researchers to check the math,” said Justin Hendrix, co-author of a report on social media and polarization and editor at Tech Policy Press, after reviewing The Markup’s data.