If you’re a drug manufacturer looking for patients, one company has become a major destination in the past few years: Facebook.

The social media giant, through its power to target users based on their interests, is especially attractive to pharmaceutical companies looking to sell drugs to potential patients. The Washington Post reported last year that health and pharmaceutical companies spent almost $1 billion on just Facebook mobile ads in 2019. The draw? Unlike a traditional TV or radio ad, Facebook’s ad categories help those companies target their drug ads at users who likely suffer from a specific illness the drug treats.

See our data here.

And data from The Markup’s Citizen Browser project—which collects Facebook data from thousands of users—shows how precise and wide-ranging that targeting is.

Though Facebook does not offer advertisers categories that explicitly identify people’s health conditions, The Markup identified dozens of ads for prescription pharmaceuticals targeted at people with “interests” in topics like “bourbon,” “oxygen,” and “Diabetes mellitus awareness.”

Indeed, The Markup found, “awareness” of a disease is a frequent proxy for illness in targeting decisions made by advertisers.

Zejula, a drug manufactured by pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, for example, is prescribed to treat advanced ovarian cancer. We found the drug targeted at users who Facebook determined had shown an interest in “cancer awareness.”

Piqray, another cancer treatment, manufactured by Swiss company Novartis, was shown to users with an interest in “National Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Several drugs were targeted at either “Diabetes mellitus awareness” or “Diabetes mellitus type 2 awareness.”

“Stroke awareness?” Brilinta, from AstraZeneca. “Multiple sclerosis awareness?” Mayzent and Kesimpta, two other products from Novartis. “Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease awareness?” Trelegy, another GSK product.

We also found drugs targeted by close proxies for other health conditions.

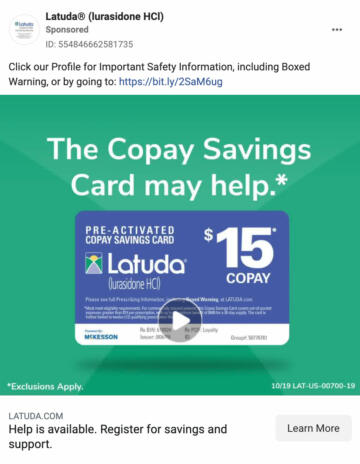

Ads for Latuda, an antipsychotic from the company Sunovion used in the treatment of bipolar depression, were shown to users with an interest in the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, a nonprofit support group. We also found it targeted at users interested in therapy and the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Anoro, a GSK drug also used to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, an inflammatory lung disease caused by emphysema and chronic bronchitis, was targeted at users interested in cigarettes, or just “oxygen.”

Ads for Nurtec, a Biohaven Pharmaceuticals product used for treating migraines, were targeted at users who showed an interest in the “international classification of headache disorders,” a medical scale of headaches.

The cancer treatment Keytruda, from Merck, was targeted at an especially wide array of users, including those interested in the chemical industry, Corona beer, and bourbon.

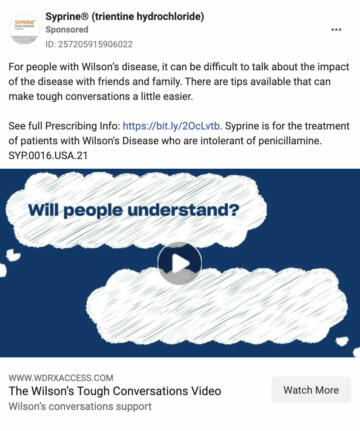

In at least one case, we found, the interest targeted was barely even a proxy. Syprine, a Bausch Health drug used to treat a rare genetic condition called Wilson’s disease, was targeted at users who’d signaled an interest in “genetic disorder.”

It’s not clear exactly how Facebook decides that a person is interested in topics such as “oxygen” or “genetic disorder.” The company only places some very specific limits on how users can target health conditions. Advertisers can’t use “sensitive” personal health data to target their ads, meaning a pharmacy, for example, couldn’t upload a list of customers with a specific illness to market to them on Facebook.

The company has also broadly defended its health privacy practices, releasing a statement in 2019 that said that “privacy and safety are particularly important for people dealing with health conditions.”

“We do not use medical history to inform the interest categories we make available to advertisers,” Facebook spokesperson Tom Channick said in a statement to The Markup. “Instead, people are placed into interest categories based on their activity on Facebook, including the pages they like or the ads they click on.”

GSK, AstraZeneca, Bausch Health, Merck, Biohaven, and Sunovion, manufacturers of some of the drugs we saw ads for, didn’t respond to requests for comment on their Facebook advertising practices. Jamie Bennett, a spokesperson for Novartis, said the company’s “goal is to reach audiences where it matters” and that it follows all regulations, both legal and those set by services like Facebook.

The potential audience size for these ads can be massive. Facebook’s ad-buying system says the number of users who have shown an interest in cancer awareness, for example, is nearly 203 million.

Other categories are more narrow. Facebook’s system said the audience for users with an interest in the depression and bipolar support alliance was a relatively slim 250,000 users.

Kirsten Ostherr, director of the Medical Futures Lab at Rice University, said there are both practical and moral problems with advertising around such medical conditions. If a work colleague walks by your computer screen and sees a targeted ad for a lung cancer drug, for example, he or she could deduce you have the condition.

If these ads are popping up on your screens everywhere, that potentially exposes information about you.

Kirsten Ostherr, Rice University

“Even if the advertiser doesn’t know exactly who you are,” Ostherr said, “if these ads are popping up on your screens everywhere, that potentially exposes information about you.”

Beyond that, targeting products by surveilling the sick inherently exploits vulnerable users’ privacy, Ostherr said.

“One of the things that is most insidious about this to me is it’s really targeting and exploiting people who are in this vulnerable state and who have found real benefit from online patient communities,” she said.

Legally, aside from providing a way for advertisers to disclose side effects, Facebook is under little obligation to shield its users’ health information. The United States’ health privacy law, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, only applies to a handful of entities that directly deal with patient health information.

Ostherr said the vagueness of Facebook’s targeting could be a “legally defensive maneuver” protecting it from liability in the future by keeping them as distant from protected health data as possible.

In 2016, a lawsuit filed against Facebook claimed that the company had unlawfully invaded users’ privacy by tracking their visits to sensitive health-related websites. The suit included a now-outdated list of health targeting options on Facebook, which included options like “cardiac arrest,” “renal failure,” and “West Nile virus.” (Facebook denied the allegations, calling the suit “an attack on the way the Internet works.”)

Subscribe to the Citizen Browser Newsletter

We’re investigating what content social media platforms amplify. Sign up for updates on what we uncover.

Courts have so far sided with Facebook in the dispute, saying its users must agree to its advertising practices when they sign up for the service and that health information isn’t necessarily more private than other types of data.

But the data Facebook does have can be enormously sensitive, as some independent researchers have shown. In 2019, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Stony Brook University reported that they were able to predict whether a Facebook user had any of 21 health conditions through language in status updates alone.

Many patients may have looked to Facebook for community and help in the past year of pandemic-enforced isolation. When someone finds support for an illness on social media, Ostherr said, it’s unlikely that the health data they’re giving away is at the forefront of their minds.

“Their priority really is not being tracked from one website to another,” Ostherr said. “Their priority is surviving.”