The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, uses investigative reporting, data analysis, and software engineering to challenge technology to serve the public good. Sign up for Klaxon, a newsletter that delivers our stories and tools directly to your inbox.

It has been more than two years since the release of ChatGPT created widespread dismay over generative AI’s threat to academic integrity. Why would students write anything themselves, instructors wondered, if a chatbot could do it for them? Indeed, many students have taken the bait, if not to write entire essays, then certainly to draft an outline, refine their ideas or clean up their writing before submitting it.

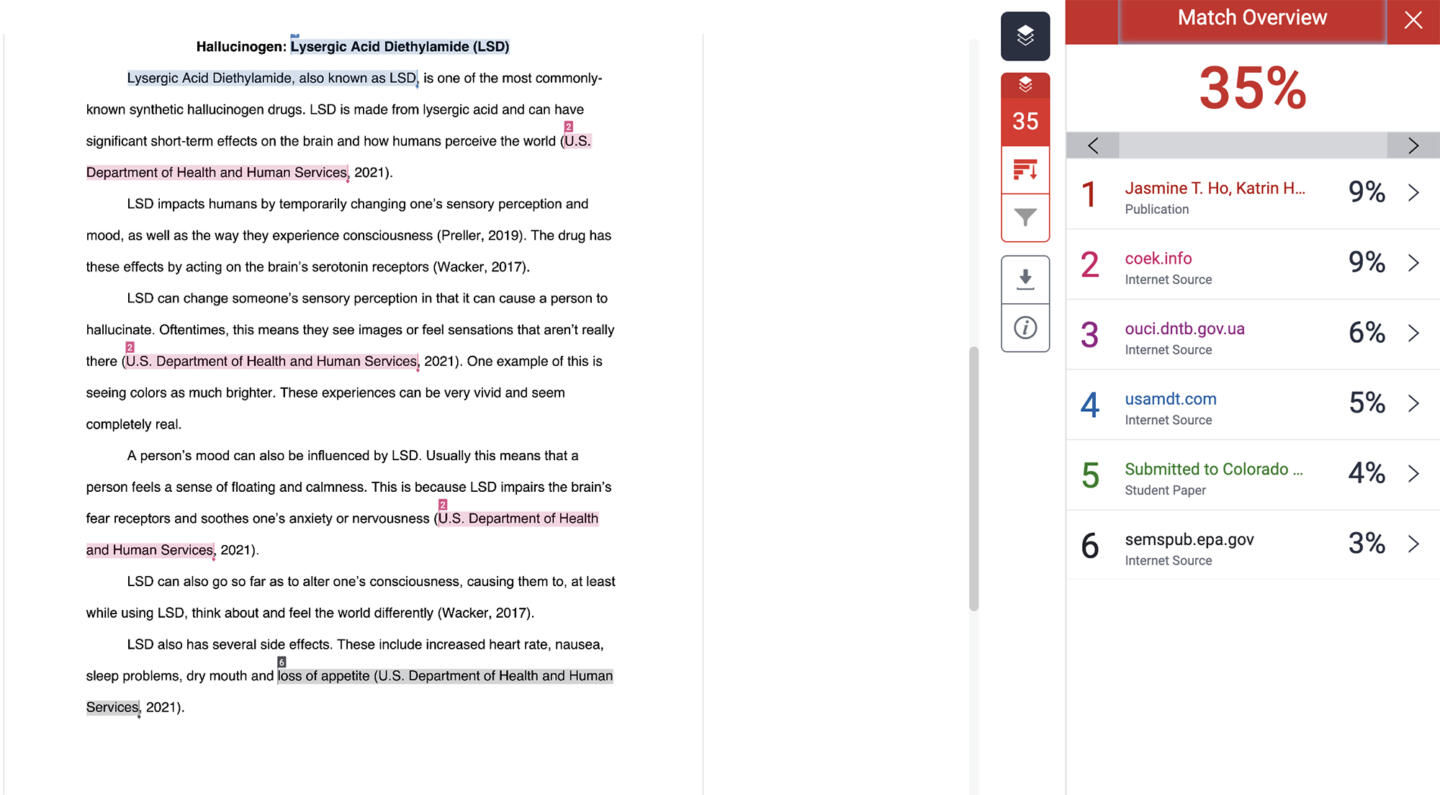

And as faculty members grapple with what this means for grading, tech companies have proved yet again that there’s money to be made from panic. Turnitin, a longtime leader in the plagiarism-detection market, released a new tool within six months of ChatGPT’s debut to identify AI-generated writing in students’ assignments. In 2025 alone, records show the California State University system collectively paid an extra $163,000 for it, pushing total spending this year to over $1.1 million. Most of these campuses have licensed Turnitin’s plagiarism detector since 2014.

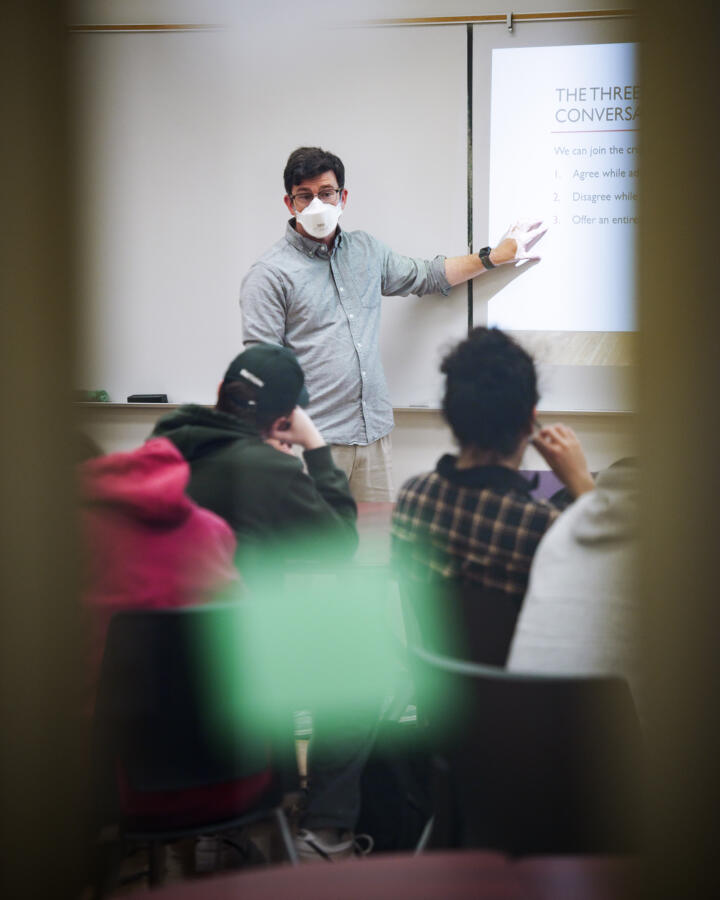

That detector first became popular among professors when the internet made it easy for students to copy and paste information from websites into their assignments. In the AI detector, faculty members sought both a way to discourage students from using ChatGPT on their homework and a way to identify the AI-generated writing when they saw it.

None of us thought about big data and how it would be used in the future.

Wendy Brill-Wynkoop, photography professor at College of the Canyons

But the technology offers only a shadow of accurate detection: It highlights any matching text, whether properly cited or not; it flags everything that mirrors AI’s writing style, whether a student used AI inappropriately or not. And Turnitin licenses this technology to colleges while demanding “perpetual, irrevocable, non-exclusive, royalty-free, transferable and sublicensable” rights to student writing. The company has used these rights to build a massive database of student papers, which it uses to market the superiority of its existing products as well as build new ones, including the AI detector. Turnitin has become so valuable that in 2019 Advance Publications paid $1.75 billion to acquire it, more than the total amount raised by all ed-tech startups the prior year, EdSurge noted at the time.

To understand the full range of consequences stemming from Turnitin’s place in higher education, it’s helpful to look at California, the state with the nation’s largest public system. CalMatters and The Markup interviewed dozens of students, faculty members and administrators across the state and obtained Turnitin purchase orders documenting the amount paid over time by approximately 60 colleges there. This investigation revealed institutions willing to renew Turnitin subscriptions year after year despite the cost, faulty technology and concerns about privacy and intellectual property raised by the company’s ever-expanding database of papers.

Turnitin tries to make the gray area of academic dishonesty into something black-and-white, and many faculty members drive demand, searching for the promise of algorithmic accuracy. But honest students are caught in the crossfire of an arms race between technology that mimics human speech and technology that claims to identify it.

The rise of Turnitin

In 2004 Wendy Brill-Wynkoop, a photography professor at College of the Canyons, chaired her campus’s technology committee. She became one of the first Turnitin users at the large community college north of Los Angeles, testing out the software before campuswide adoption. Purchasing records obtained by CalMatters and The Markup show Brill-Wynkoop’s license cost just $120 in 2004. The following year, College of the Canyons paid 75 cents per student and less than $6,500 total to make the tool available to all faculty members for as many papers as they wanted to scan. This year, the college paid almost $47,000.

As teaching and learning increasingly shifted online throughout the early 2000s and 2010s, Turnitin became more embedded in classes. College of the Canyons, like many institutions, paid extra to integrate the plagiarism checker into its online learning management system, where faculty members had begun to post assignments and reading materials and students were expected to submit their papers. Turnitin’s default settings, once integrated, are to scan every assignment, not just those that professors suspect are plagiarized. Besides accelerating the growth of the company’s student-paper database, this puts the tool in front of faculty members who otherwise wouldn’t have used it.

In fact, Brill-Wynkoop had largely stopped using Turnitin to check student work after a few years. “If I had a student who I suspected wasn’t using their own words, I’d pop the phrase into Google and then could just show them,” she said. “I wouldn’t have gone back to [Turnitin].” But since her college built it into the system she was already using to read student papers, she found herself checking the automated reports again.

When the pandemic shut down in-person instruction on campuses nationwide in 2020, fresh anxiety over academic integrity created another windfall for Turnitin. The GovSpend database of government-purchasing records shows a nationwide spike in Turnitin contracts during the 2020-21 school year. And in California, at least, many colleges processed more cheating accusations that year, too, according to academic dishonesty case counts obtained by The Markup and CalMatters via public-records requests. Those case counts dropped — sometimes precipitously — with the return to in-person learning but climbed again when the release of ChatGPT gave Turnitin its next crisis to monetize.

This year’s $47,000 contract with Turnitin for plagiarism and AI detection pushed the total spent by College of the Canyons to over half a million dollars.

Turnitin executives did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. Worldwide, the company licenses its software to more than 16,000 institutions that cumulatively enroll over 71 million students. Almost three-quarters of California community colleges now use it, as does the entire California State University system, except Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. Cal Poly canceled its contract last year saying not enough faculty used Turnitin to justify the cost, but not before it spent $171,000 on the detectors from 2020 to 2024. Cal State campuses have spent a combined $6 million on Turnitin since 2019 alone, according to records obtained by CalMatters and The Markup. Several University of California campuses spend more than $100,000 per year on the detector, which Turnitin licenses for a per-student fee.

As part of this investigation, CalMatters and The Markup tracked down more than $15 million in purchases of Turnitin plagiarism-prevention software across 57 institutions. Of course, since California is home to 149 public colleges and universities, this amount represents just a fraction of the total spending statewide. And while College of the Canyons released 21 years of receipts, most campuses shared only three to seven.

Robbie Torney is the senior director of AI programs at Common Sense Media, a national nonprofit headquartered in San Francisco that does research and advocacy work around how young people use technology. He said $15 million is a lot of money to spend on a tool with such limited value. He pointed to troubling reports of Turnitin erroneously flagging student writing as AI-generated and equally troubling accounts of students using simple workarounds to undermine the AI detectors.

“It’s probably better to invest in training for professors and teachers,” Torney said, “and also creating some frameworks for universities to message to students how they can and can’t use AI, rather than trying to use a surveillance methodology to detect AI in student writing.”

Yet many faculty members still want the tool, and colleges have continued paying for it year after year. Records show the Los Rios Community College District, in the Sacramento area, has paid almost $750,000 since 2018 to license Turnitin’s antiplagiarism software. In the Los Angeles Community College District, this year’s license alone cost $265,000. And UC Berkeley is just a few years into a 10-year, nearly $1.2-million contract of its own.

Amassing student papers

Turnitin helps convince college leaders to buy its tools by arguing it knows student writing better than any other company in the world. It has been making this case for decades by pointing to the size of its database, regularly updating its website with the latest student-paper count — 1.9 billion as of June 2025.

Brill-Wynkoop heard the same pitch back in the early 2000s: Instructors could catch a student turning in a peer’s paper from a previous semester with Turnitin. But the company doesn’t need to keep papers for decades to accomplish this.

The Community College League of California signed an agreement in 2016 with a company called VeriCite, locking in pricing for any of the state’s 116 community colleges that wanted its plagiarism-prevention software. VeriCite also claimed to help colleges catch students turning in their peers’ papers. But the tool only made student papers searchable to faculty members on campuses covered by the contract, and it gave them a chance to opt out of letting VeriCite pool their students’ work. The company claimed no rights to student intellectual property or copyright over their work.

After Turnitin bought the company in 2018, a new set of terms and conditions took effect: Now student papers go into Turnitin’s global database and the company maintains a perpetual, royalty-free license over all of them.

When Turnitin acquired another plagiarism-detection company, Unicheck, in 2020, the El Camino College student newspaper reported that the institution switched vendors rather than put up with Turnitin’s contract terms. Still, the vast majority of colleges and universities across California continue to hand over student writing to Turnitin in the name of plagiarism prevention.

Jesse Stommel, an associate professor at the University of Denver, started speaking out about the company’s database of student papers in 2011, when he discovered his dissertation was in it. As a writing instructor, he takes issue with schools unquestioningly handing over original student work to a for-profit company.

Turnitin monetizes student intellectual property and contributes to a culture of suspicion in education.

Jesse Stommel, associate professor at the University of Denver

In his syllabus, where the university requires him to include a statement about Turnitin, Stommel tells students, “It is my commitment to you that I will not submit any of your work to Turnitin. Plagiarism-detection software like Turnitin monetizes student intellectual property and contributes to a culture of suspicion in education. I trust you. I trust that your work is your own.” He then encourages students to ask him if they have questions about how to properly cite sources and directs them to an essay he co-wrote if they want to learn more about Turnitin or how to protect their intellectual property.

Students have protested Turnitin use too. An undergrad at McGill University, in Canada, failed multiple assignments in 2003 after refusing to submit them to Turnitin. He appealed to the university administration, ultimately winning the right to have his papers graded without the technology.

In 2007, high schoolers in Virginia and Arizona sued iParadigms, Turnitin’s parent company at the time, arguing that its database violated their copyright over their own writing. The courts disagreed. The students also lost on appeal, but some colleges still warn their faculty against using free online plagiarism checkers because of privacy concerns inherent in handing student work over to third-party companies.

Turnitin says it doesn’t “monetize” student writing, per se, but it has raised its prices since releasing an AI detector, which the company developed using that writing.

Brill-Wynkoop said she and her colleagues never thought that the student-paper database could one day become a source of profit for Turnitin. “That makes me feel bad as a faculty member, that I encouraged my students to use something, and now, I don’t know,” she said. “None of us thought about big data and how it would be used in the future.”

‘Caught in the middle’

For today’s undergraduates, routine surveillance and violations of privacy are an unavoidable part of college life. Emily Ibarra, who just finished her second year at Cal State Northridge, said she has never even used ChatGPT. Yet, like all students on her campus and many millions more across the country, she has to deal with the consequences of widespread suspicion about her generation’s integrity.

“That culture is getting normalized here, of professors being able to take the furthest lengths possible to make sure [students aren’t cheating],” she said. “It kind of makes you feel defeated before you even start.”

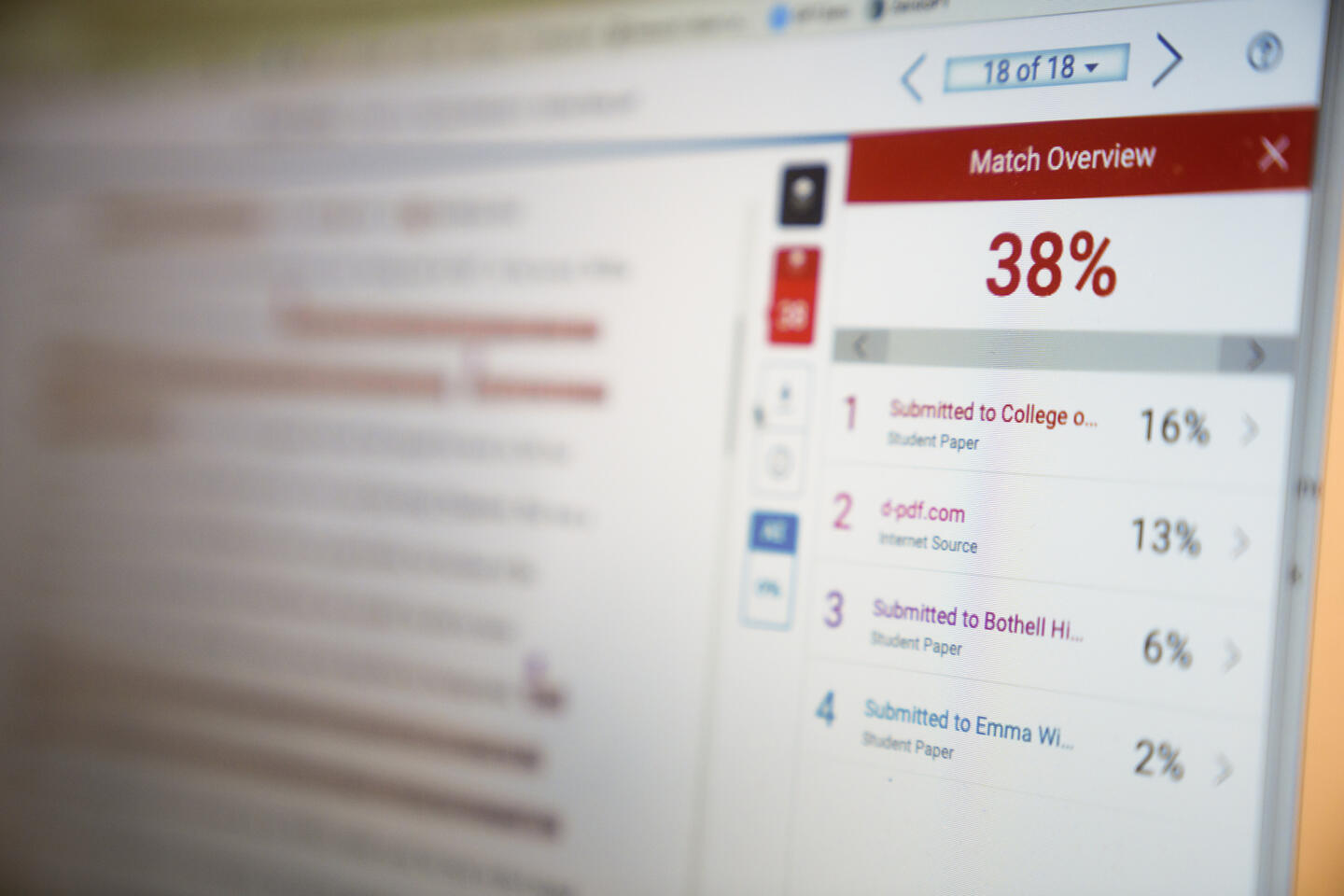

When Ibarra started college, she panicked at the sight of her first Turnitin “similarity report.” Some faculty members let students see the reports as soon as they turn in their assignments, while others show students the reports only if they want to discuss a problem.

“At first I didn’t know what it was,” Ibarra said. “It shows green, yellow, red, so at first I thought it was grading the quality of my writing.” On a short assignment, she said, it’s almost impossible to avoid a “yellow” report because Turnitin’s text-matching scanners will flag quoted material and suggest it could be plagiarized. So far, none of Ibarra’s professors have accused her of academic dishonesty, but the risk, she said — even if she doesn’t intentionally plagiarize or use ChatGPT — is “really stressful.”

Ibarra has a tool called Grammarly installed on her computer that she has been using since high school to catch spelling and grammar mistakes; only now, she said, some professors at Cal State Northridge tell students not to even use spell-check tools because they’re bolstered by AI. Microsoft Word, Google Docs and Grammarly now all rely on the same algorithms that create ChatGPT’s human-sounding responses to suggest improvements to users’ writing. Ibarra says she uses Grammarly only to correct misspellings and missed commas, but, like other students interviewed for this story, she isn’t always sure when appropriate use of ubiquitous technology veers into academic dishonesty.

To be falsely accused felt devastating.

Nilka Desiree Abbas, student at San Bernardino Valley College

Joshua Hurst, who just finished his junior year at Cal State Northridge, said Turnitin flagged his writing in the spring of 2024. He hadn’t used ChatGPT to craft the assignment, but he had used Grammarly to clean up his writing before turning it in. His professor didn’t dock his grade, but Hurst knows other professors might have. Now he runs his writing through two different checkers before submitting anything.

Hurst is excited about AI-driven innovation and is glad to be part of a generation that gets to experience it, but the lack of consensus over acceptable AI use and the threats posed by faulty detectors make him shake his head.

“Students,” he said, “are the ones who are caught in the middle.”

The Center for Democracy & Technology, a D.C.-based nonprofit focused on research and advocacy around digital rights, surveyed high schoolers about their experiences with a range of educational technologies last summer. At the request of The Markup, now a part of CalMatters, researchers asked students whether they or anyone they know had been wrongly accused of using generative AI to cheat. One in five said yes.

When Common Sense Media surveyed a nationally representative group of teenagers about their AI use last year, it found that Black teens were twice as likely as white and Latino teens to say their teachers had flagged their work as AI-generated when it wasn’t. In their report about the survey, researchers attributed this difference, in part, to teachers’ bias. Black students have long been disciplined at far higher rates than their peers.

Other researchers have pointed to the vulnerability of non-native English speakers subjected to these detectors because their writing is likely to use simpler syntax and a more limited vocabulary, which happens to be typical of AI-generated writing.

Nilka Desiree Abbas suspects that’s why she was accused in the summer of 2023. A native Spanish speaker, she was taking a political science course at San Bernardino Valley College and got a zero on an assignment along with a curt message from her professor saying she had used ChatGPT. But Abbas, who is from Puerto Rico, said she hadn’t.

“It took me so long to go back to school,” she said with a toddler at her side. “To be falsely accused felt devastating.” She ultimately passed the class with a B and graduated with a degree in administration of justice the following spring, but she was shaken. She took photos of her progress on assignments in her remaining courses to create an evidence trail of original work.

Machine Learning

AI Chatbots Can Cushion the High School Counselor Shortage — But Are They Bad for Students?

The more students turn to chatbots, the fewer chances they have to develop real-life relationships that can lead to jobs and later success

Turnitin has since fine-tuned its detector to avoid accusing non-native English speakers more often than native English speakers, but it acknowledges its detector still gets it wrong sometimes. And stories like Abbas’s have saturated Reddit communities and TikTok feeds, creating anxiety even among students who don’t think they cross any academic integrity lines while completing their assignments.

CalMatters and The Markup spoke with more than a dozen current undergrads, and virtually all of them described strategies to reduce the likelihood of being wrongly accused. A freshman said she adds typos to her writing to distinguish it from AI’s. Many students said they check their papers with Turnitin before submitting them, when professors allow it, and with additional online detectors for good measure. This step has become a form of due diligence for students, most of whom describe at least some level of concern that they could be accused without having done anything wrong.

Jasmine Ruys, who oversees student conduct cases at College of the Canyons, said she often sees students who think they were wrongly accused but unwittingly used AI.

“There are students who go to other colleges where that college purchases Grammarly, the pro version, installs it on their computers to help them and when they turn it in to our instructors, it gets caught by the AI detector,” Ruys said. “It’s hard because students think they’re doing the right thing and they’re getting caught up in it because [AI] is just embedded in everything.”

The illusion of a solution

Turnitin’s original text-matching software wasn’t especially sophisticated at detecting actual plagiarism, but at least it could point to the original source behind its accusations, and a faculty member had something to assess; they could ignore the text Turnitin highlighted because students were quoting reading material or citing an appropriate source. The AI detector determines what portion of an assignment was probably generated by AI but leaves it to faculty members to puzzle through whether that AI-like text represents a violation of academic integrity.

Adam Kaiserman has taught English at College of the Canyons for more than a decade. Unlike some of his colleagues who forgo Turnitin’s technology, he looks closely at the software’s similarity reports. And while he said he plans to keep using the tool, he didn’t describe it as very helpful. Student habits have shifted. Both Kaiserman and Ruys said they almost never see traditional plagiarism in Turnitin’s text matches anymore; students who are inclined to cut corners will just use AI chatbots instead. And the software misses much of the AI-generated writing it scans, in part because Turnitin has become more conservative about what it flags to avoid accusing honest students. The software also doesn’t scan for content accuracy, leaving a key tell of AI writing undetected.

“The biggest tipoff [of AI use] are fake quotes or hallucinations, which Turnitin isn’t good at catching,” Kaiserman said. When a paper mentions a person who doesn’t exist or a quote that never appeared in the reading, what many refer to as “hallucinations,” Turnitin has no idea. It just measures how much the writing mirrors the style of AI-written text.

While many students are as honest as ever, plenty have started to use AI. They describe using ChatGPT on assignments they don’t care about, reserving their full effort for papers they see as a higher priority. Sometimes they outsource deeper thinking and planning to AI when they are stumped by a blank page and want help with how to write an introduction or structure a paper. In the Common Sense Media survey, 63% of teens said they had used a chatbot or text generator for school assignments.

Now, many colleges make chatbots available to students for free, driving even wider use. A survey of undergraduates in the United Kingdom this past December found 88% had used AI on assignments, mostly to explain concepts, summarize content and suggest research ideas, but 18% of those surveyed said they had submitted work that included some AI-generated text.

Ed tech does a good job of convincing you that it is huge, permanent, there, 100% necessary for education. That’s its big lie.

Sean Michael Morris, longtime educator

At College of the Canyons, Ruys has found that when students do use a chatbot to complete a paper, it’s usually because they had too much on their plate with school, they were preoccupied with work or family commitments or they didn’t understand the assignment. Instead of going to their professors, they went to AI. During academic-dishonesty hearings, she guides students to campus resources that can help them better manage their workloads. But she considers a lot of AI use to be in an ethical gray area, including when students write a first draft themselves and then polish it with an AI tool.

“Isn’t that very similar to our tutors?” Ruys mused.

Administrators from the California State University Office of the Chancellor, Cal State Northridge and the Los Angeles Community College District, all of whom occasionally teach, said they don’t use Turnitin in their own courses, even if they defend their institutions’ software licenses more broadly. Stanford University doesn’t license the technology at all, advising its faculty that the tools can erode feelings of trust and belonging among students and raise questions about their privacy and intellectual-property rights.

Stommel, the University of Denver professor, said faculty members often believe cheating is on the rise and that detectors are one of the only ways to keep students honest. But he shares evidence that cheating rates have long remained largely flat, even post-ChatGPT. He also pans the use of Turnitin as a scare tactic. “We see this with the criminal-justice system,” he said. “Deterrence doesn’t actually work.” What does work, he argues, is building trusting relationships with students. “Turnitin immediately fractures that relationship with students.”

Sean Michael Morris, a frequent co-author of Stommel’s and a longtime educator, also tries to convince faculty members they don’t need Turnitin despite the company’s marketing, which champions its value to academic integrity.

“Ed tech does a good job of convincing you that it is huge, permanent, there, 100% necessary for education,” he said. “That’s its big lie.”

Natasha Uzcátegui-Liggett and CalMatters College Journalism Network fellows Delilah Brumer and Jeremy Garza contributed reporting and research.

The Kapor Foundation supported this project through its Research Fellowship program.