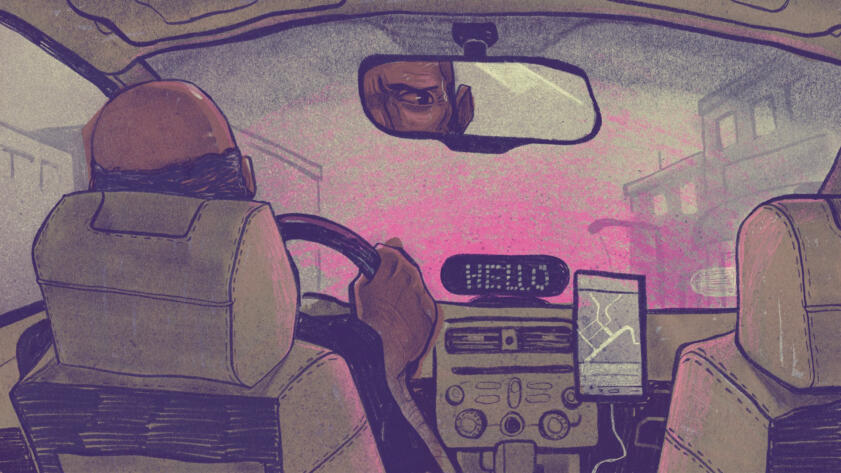

When the St. Louis police arrived on the scene last April, Lyft driver Elijah Newman was already dead. Officers found him in the driver’s seat of his car with a gunshot wound to his torso. In a probable cause statement provided to The Markup by the Circuit Attorney’s office, detectives say they located a bullet casing next to Newman’s body and a Lyft light affixed to the front dashboard.

“It was like a fist to the gut,” Elizabeth Hylton, Newman’s long-time friend and roommate, said when she heard the news.

See the data here.

Newman, an immigrant from Ghana, was one of more than 50 gig workers murdered while on the job over the past five years in the U.S., according to a new study published by worker advocacy group Gig Workers Rising.

The study draws data from The Markup’s report on 124 carjackings of ride-hail drivers, as well as news articles, police documents, legal filings, GoFundMe fundraisers, and other online searches. Gig Workers Rising said the study fills the void of any company or government data on the dangers of gig work. The Markup independently verified the incidents listed in the report.

“These are not one-off incidents,” said Lauren Jacobs, executive director of a coalition of nonprofits that focus on inequality, PowerSwitch Action, which contributed to the report. The companies don’t seem to be concerned enough with worker safety, she added.

“This is a pattern.”

According to a spreadsheet that Gig Workers Rising provided to The Markup, 22 of the workers were driving for Uber when they were killed, and four were couriers for Uber Eats. Seventeen were working for Lyft (Lyft disputes this number), eight for DoorDash, two for Instacart, one for Grubhub, and one for Postmates (which is owned by Uber). The Markup also independently verified the incidents in the spreadsheet, a handful of which the companies said happened after the worker had logged off the app.

Lyft spokesperson Gabriela Condarco-Quesada said that the names of three of the drivers listed in the spreadsheet, Glynon Nelson, Rossana Delgado, and Terrell Harris, “did not occur on the Lyft platform.” In Delagado’s case, the investigation is ongoing and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation told The Markup that “our investigation has not revealed any evidence that shows that she worked for Lyft.”

In Nelson’s case, a probable cause affidavit provided to The Markup by the Superior Court of Lake County stated that Nelson was driving for Lyft the night of the incident and picked up two passengers who then allegedly killed him. Nelson was driving on the account of another Lyft driver at the time.

In Harris’s case, Philadelphia Police Department chief inspector Scott Small said in a press conference, “The vehicle is registered to the victim. Now, the vehicle does have a Lyft sign on the right side of the front windshield, so this is a possible Lyft vehicle. Don’t know if the shooting victim was in the process of driving for Lyft at the time, but the vehicle does have a Lyft sticker on the windshield.”

It’s estimated that more than one million people in the U.S. work for one or more of these gig companies. The assaults happened across the country, from Arizona to Kentucky to Pennsylvania, and the majority happened in 2021, with 28 reported homicides. Seven murders tracked by Gig Workers Rising occurred in the first two months of this year alone.

Some of the workers were accidentally caught in drive-by shootings, others in road rage incidents or botched carjackings and robberies. While cities across the country have seen a rise in carjackings and associated crimes over the last couple of years, these incidents appear to be happening to gig workers at an especially high rate.

Working for an Algorithm

Uber And Lyft Drivers Are Being Carjacked at Alarming Rates

The Markup confirmed 124 carjackings and attempted carjackings of ride-hail drivers across the country. Drivers say the companies are doing little to help

“Gig work is becoming increasingly dangerous,” said Bryant Greening, an attorney and co-founder of Chicago-based law firm LegalRideshare, who says he gets calls from gig workers who’ve been carjacked on a weekly basis. “Criminals see rideshare and delivery workers as sitting ducks, susceptible to carjackings, robberies, and assaults.”

Uber spokesperson Andrew Hasbun said, “Given the scale at which Uber and other platforms like ours operate, we are not immune from society’s challenges, including spikes in crime and violence.” He added that “we continue to invest heavily in new technologies to improve driver safety,” and “each of these incidents is a horrific tragedy that no family should have to endure.”

Lyft’s Condarco-Quesada said, “Since day one, we’ve built safety into every part of the Lyft experience. We are committed to doing everything we can to help protect drivers from crime, and will continue to invest in technology, policies and partnerships to make Lyft as safe as it can be.”

DoorDash spokesperson Julian Crowley, Instacart’s senior director of shopper engagement Natalia Montalvo, and Grubhub spokesperson Jenna DeMarco provided similar comments, saying that the companies take safety seriously and have protocols in place for emergency situations.

Gig Workers Rising said the tally of more than 50 workers “is not comprehensive and likely excludes many workers.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics and most police departments don’t compile data specifically on gig worker deaths. None of the gig companies The Markup contacted would say how many of their workers have been killed on the job. Uber’s Hasbun and Lyft’s Condarco-Quesada pointed The Markup to company safety reports, both of which had some data on fatal physical assaults for riders and drivers. The most recent data was from Lyft in 2019.

Gig Workers Rising said its spreadsheet includes only reported homicides, not traffic accidents or other causes of death. Most of those killed—63 percent—were people of color, according to the group, which also reported that several families say they received little support from the companies after the incidents.

Gig workers are treated as independent contractors by the companies, so they’re not given employee benefits like workers’ compensation, full company health insurance, or death benefits. When something goes wrong during rides or deliveries, workers and their families are often the ones shouldering medical costs, car payments, and funeral expenses.

Two drivers told The Markup that after they were carjacked, Uber and Lyft offered to help with some of their expenses only if they agreed to sign nondisclosure agreements.

Uber’s Hasbun didn’t respond to questions about nondisclosure agreements but said that “every situation is unique, we have programs in place to support families, including with insurance.” Similarly, Lyft’s Condarco-Quesada said, “While every situation is unique, our specialized group of trained Safety advocates work with the driver’s family to determine their specific needs and provide meaningful support to them directly.” Crowley, Montalvo, and DeMarco also said DoorDash, Instacart, and Grubhub reach out to support workers’ families in these instances and both DoorDash and Instacart offer injury protection insurance for free to eligible workers.

Along with its report, Gig Workers Rising demanded reforms from the companies, which included workers’ compensation for all drivers and couriers, the end to forced arbitration clauses in contracts so that workers can publicly pursue legal claims in court, and a requirement that the gig companies report worker deaths annually.

“No one when they show up to work should be killed,” Cherri Murphy, a former Lyft driver and organizer with Gig Workers Rising, said in a statement. “The lack of care for these workers is a direct outcome of a business model set up to milk as much as possible for executives.”

Some families have filed wrongful death lawsuits against the companies. Among them are the relatives of Uber driver Cherno Ceesay, a 28-year-old immigrant from Gambia who was allegedly fatally stabbed by two passengers while driving in Issaquah, Wash., and the family of Beaudouin Tchakounte, a 46-year-old Cameroonian immigrant who also drove for Uber and was allegedly shot to death by a passenger in Oxon Hill, Md.

A federal district court judge in Maryland dismissed Tchakounte’s case in February, but the family is appealing. Ceesay’s case is pending trial in a Washington federal district court later this year.

Uber’s Hasbun didn’t respond to requests for comment on the lawsuits.

Isabella Lewis was 26 years old when she was allegedly killed by a passenger in August 2021 near Dallas, Texas. According to Gig Workers Rising, Lyft hasn’t assisted the family, which started a GoFundMe page to raise money for Lewis’s funeral. Lewis’s sister, Allyssa Lewis, told Gig Workers Rising, “My sister lost her life over a Lyft trip that totaled … 15 dollars.”

After publication of this article, Lyft’s Condarco-Quesada told The Markup that “on the same day we learned of this tragic incident, we attempted to reach Ms. Lewis’ family to offer our support. Unfortunately, we were unable to make contact with them.” Condarco-Quesada declined to provide additional details about how Lyft reached out to Lewis’s family and whom the company attempted to contact.

Simply stated, gig workers and their families are left to fend for themselves.

Bryant Greening, LegalRideshare

The Markup previously found that many gig drivers who were victims of carjackings were elderly, immigrants, and women. In addition to the 124 carjackings we first compiled, we also found that in Minneapolis alone nearly 50 Uber and Lyft drivers were carjacked during a two-month period from August to October 2021.

Some of the carjackings were random incidents, we found, but the majority of the attacks happened after drivers were paired with their would-be assailants by Uber’s or Lyft’s app—often with the passengers using fake names and fake profile pictures. Neither company requires riders to use a valid ID to sign up for the service, so passengers can be anonymous. The suspect in Elijah Newman’s case reportedly used a false name. Gig Workers Rising said this happened in some of the cases it tracked too.

Uber’s Hasbun said the company now requires new riders who sign up for the app and use anonymous forms of payment, like a gift card, to provide a valid ID. Lyft also has this requirement in a few U.S. cities. Neither Hasbun nor Lyft’s Condarco-Quesada responded to questions about why the companies don’t require all passengers to upload a valid ID.

“While the companies publicly tout their commitments to safety, workers quickly discover an alternative reality,” said LegalRideshare’s Greening. “Simply stated, gig workers and their families are left to fend for themselves.”

Update and Correction

The spelling of the first name of Allyssa Lewis has been corrected. The article has been updated to reflect comments from Lyft that came in after press time, including three names of drivers the company says “did not occur on the Lyft platform.”