For those of you worried about the Supreme Court breaking the internet, you can breathe easy. The court left Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act unscathed—for now—in opinions released today on two closely watched cases that many observers worried could shake the foundations of online discourse had they gone differently.

In a pithy three-page opinion, the court vacated Gonzalez v. Google. The case explored whether Google was liable for acts of terrorism perpetrated by the Islamic State group in Paris in 2015 because the group used YouTube to spread violent messages. A related case, Twitter v. Taamneh, examined whether arguing that online platforms were responsible for the effects of violent content posted by the terrorist group. In a more lengthy opinion authored by Justice Clarence Thomas, the court unanimously found that platforms are not liable under the Antiterrorism Act. Section 230, one of the more important legal provisions of the modern internet, has escaped intact. However, there are a number of interesting wrinkles to consider here, including some hints at where the next challenge to Section 230 may arise.

First, a quick recap: Back in February, the court entertained oral arguments in both cases, taking a close look at liability for choices made by internet platforms. As Kate Klonick, law professor at St. John’s University and fellow at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard, explained brilliantly here, the narrative arc of Taamneh and Gonzalez should be understood in political context—specifically, partisan calls for the need for social media regulation.

Nevertheless, the question at the heart of Gonzalez—whether Section 230 protects platforms when their algorithms target users and recommend someone else’s content—prompted a flurry of concern and an avalanche of amicus briefs discussing why this would break the internet as we know it. (In a Q&A for us, James Grimmelmann, professor at Cornell Law School and Cornell Tech, explained how disruptive this would be for generative AI, too.) Today, the court punted on the case in its opinion, saying it would be resolved by the court’s logic in Taamneh.

Taamneh looked at whether Twitter’s failure to remove certain Islamic State content constituted “aiding and abetting” a terrorist attack against a nightclub in Istanbul. The court rejected Taamneh’s claim, explaining that aiding and abetting constitutes “conscious, voluntary, and culpable participation in another’s wrongdoing.” In lay terms, it has to be specific and intentional. Justice Thomas, writing for the court, reasoned by analogy to earlier technologies: “To be sure, it might be that bad actors like ISIS are able to use platforms like defendants’ for illegal—and sometimes terrible—ends. But the same could be said of cell phones, email, or the internet generally.”

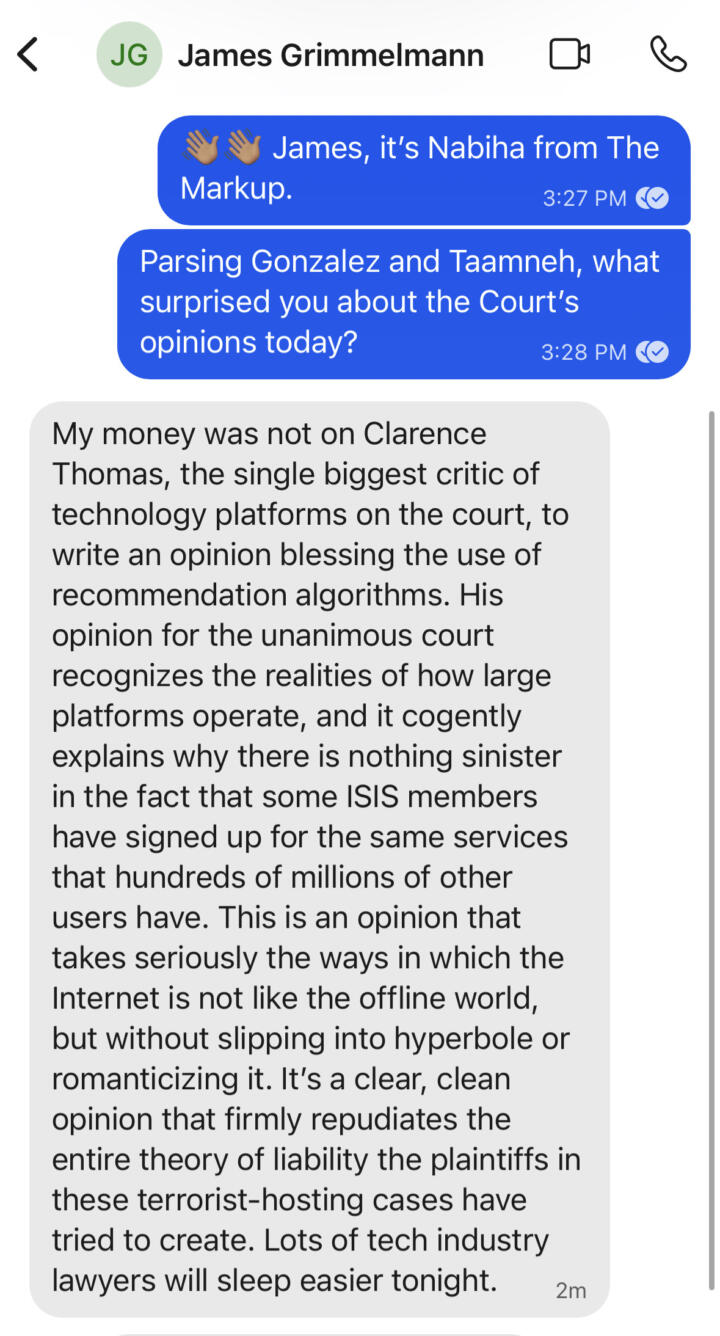

Fascinatingly, this opinion was authored by Thomas, the very same justice who’s been clamoring for increased regulation of social media. Grimmelmann weighs in:

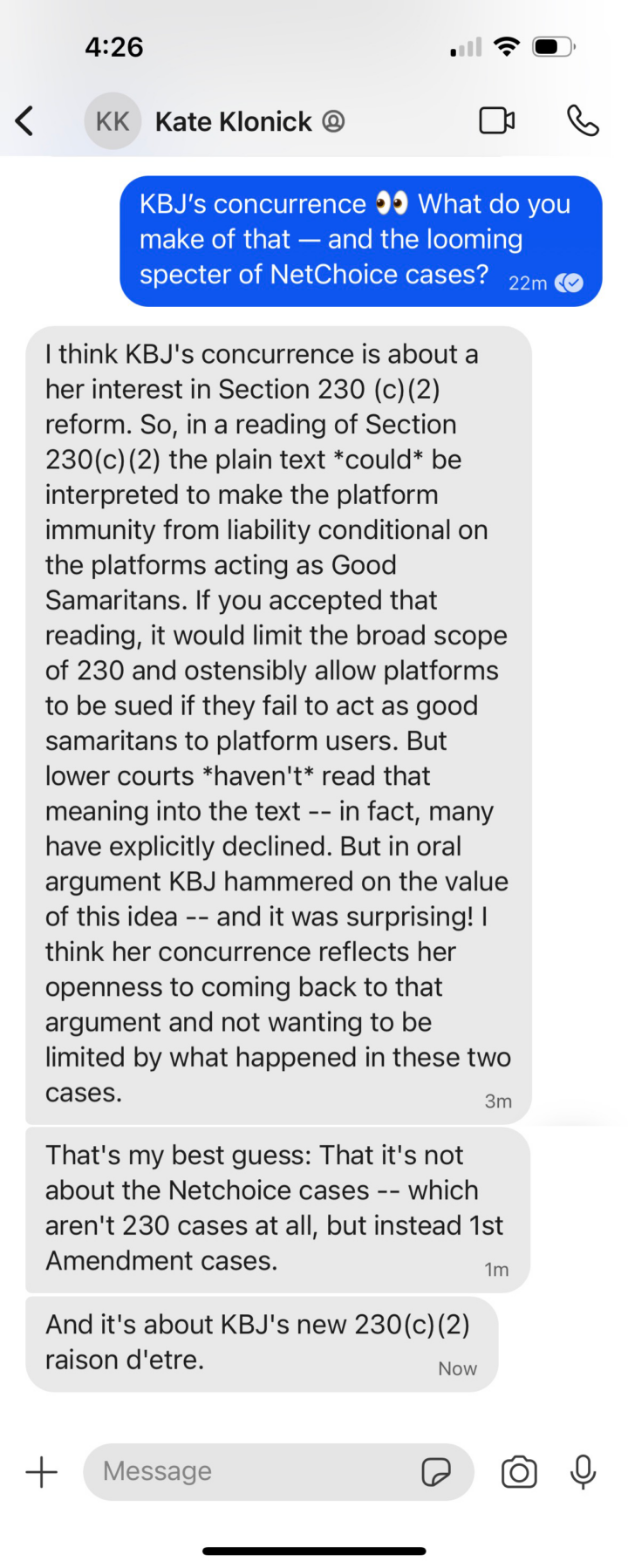

Even more interesting? Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson filed a brief concurrence in Taamneh, noting that “Other cases presenting different allegations and different records may lead to different conclusions,” and in deciding today’s cases, the court “draws on general principles of tort and criminal law to inform its understanding… General principles are not, however, universal.”

I sent Kate a Signal message to read the tea leaves from Justice Jackson, and what that might mean for the future of Section 230:

So while tech industry lawyers might sleep a bit easier tonight, there’s still more to come. Stay tuned for more internet law intrigue in the coming months as we wait for the Solicitor General’s perspective in the NetChoice cases around social media regulation laws in Florida and Texas. Briefing in those cases is likely to come in the fall, and The Markup will be here to help you make sense of that.