Hello, friends,

When Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen was asked what she would do if she could only do one thing to change Facebook, she said she would make the company disclose what’s popular on its platform.

“If I could only do one thing, I would improve transparency,” she said in a podcast with The Wall Street Journal. “Because if Facebook had to publish public data feeds daily on the most viral content, how much of the content people see is coming from groups? How much hate speech is there? If all this data was transparent in public, you’d have YouTubers who would analyze this data and explain it to people.”

Well, we’re not exactly YouTubers here at The Markup (although we do have a YouTube channel), but with our Citizen Browser project we have been doing our best to provide, at the very least, a partial answer to Haugen’s call for transparency.

This week we published an investigation by data reporter Corin Faife into what is really trending on Facebook and launched an accompanying Twitter bot called Trending on Facebook that provides daily updates based on data collected from our national panel of paid users who automatically share data with us from their Facebook feeds.

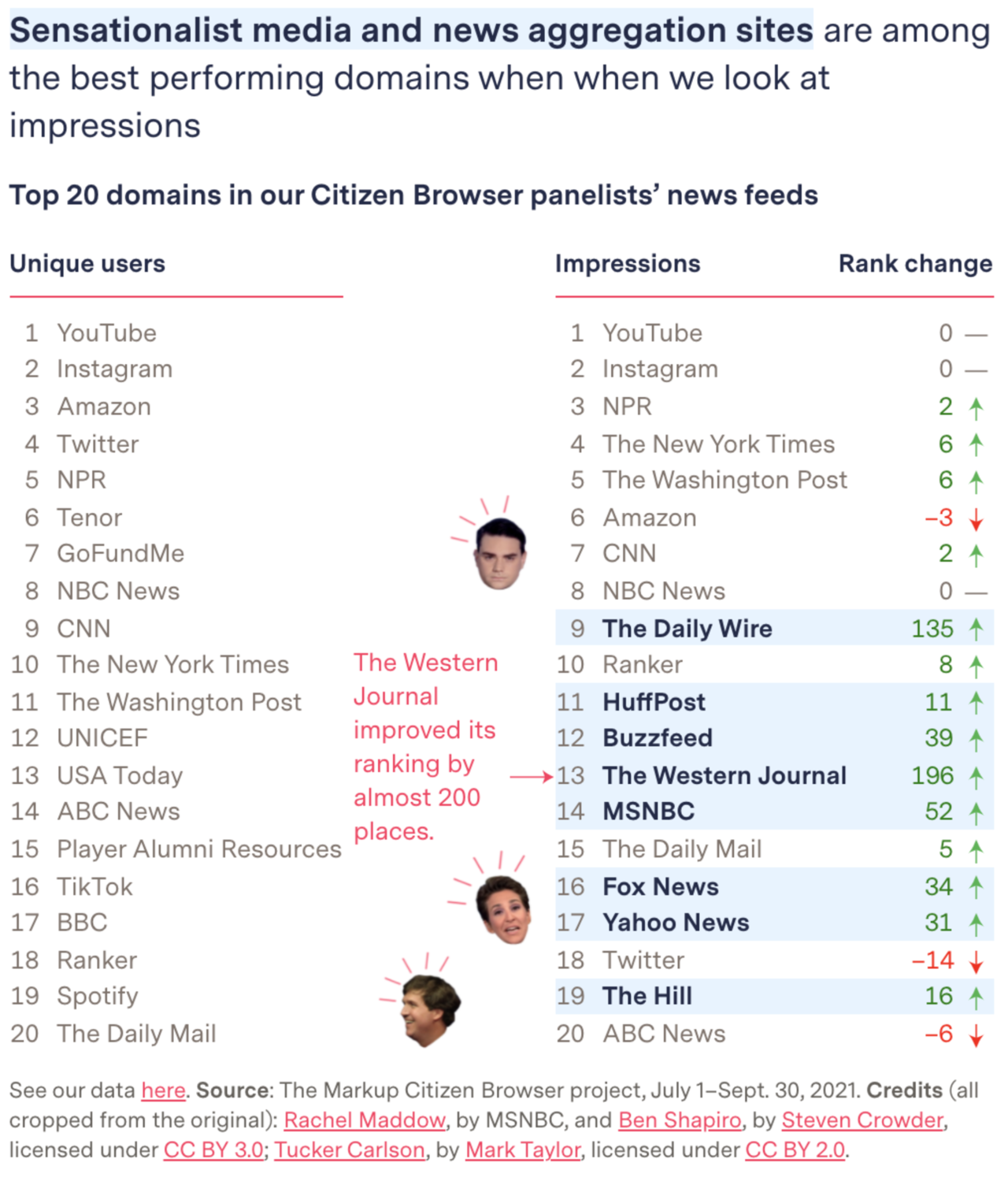

What our reporting reveals is different from what you will see in Facebook’s latest Widely Viewed Content Report, issued last week, which says that top content on its platform comes from sources like UNICEF, ABC News, and the CDC.

When we ran the numbers, we found that sensational, partisan content from The Daily Wire and The Western Journal moved up in the ranks to become top performers.

The reason for the difference is simple: The rankings in Facebook’s report are based on “reach”—which is how many unique viewers saw each domain. But we measured an equally if not more important metric, “impressions”—which is how often content from the same site bombards users’ feeds.

In other words, the 58-year-old female Citizen Browser panelist in New Mexico who saw articles from the far-right news site Newsmax in her feed 1,065 times from July through September of this year would count as 1,065 impressions under our calculations—but under Facebook’s calculation would count as one single unit.

That means that the overall rankings of popular content look considerably different when we measure them by impressions instead of Facebook’s reach measurement.

When asked about our metrics, a Facebook spokesperson said the company plans to “refine and improve” its reports but did not say whether the company would eventually include impressions in its quarterly Widely Viewed Content reports.

Our Trending on Facebook analysis was only possible because we were able to statistically validate that our Citizen Browser panel, while relatively small, is a fairly representative sample of Facebook users.

Using Facebook’s reach metric, we found that the most popular domains shown to our panel matched those in Facebook’s Widely Viewed Content Report. Data scientist Micha Gorelick used a metric called Kendall Tau-c ranking correlation to see how comparable our most popular list was to Facebook’s list. She found a strong correlation.

Micha also tested our data using another metric, the Spearman correlation coefficient, to show the similarity between the number of unique users seeing each domain. Again she saw a strong correlation.

This analysis allowed us to conclude that our data is a good match to the released Facebook data and that our sample is sufficient for statistical relevance. Once we understood that, we felt comfortable in our calculations of impressions and frequency. (Read the full methodology here.)

Of course, we know the popular content probably looks different—and is perhaps more extreme—in countries where we don’t have Citizen Browser panels running and where Facebook spends even less time and energy moderating content.

In her time at Facebook, Haugen said, she would go to weekly “Virality Review” meetings where employees would review the top 10 posts in countries that were at risk for genocide. “It’s just horrific content. It’s severed heads. It’s horrible,” she said about the posts that were going viral in those countries.

And yet, Haugen said, her five-person civic integrity team wasn’t able to adequately monitor those countries. “You’re sitting there being like, I am the civic misinformation PM [project manager], and I am seeing this misinformation and I feel no faith that I can do anything to address it,” she said in the podcast. “Imagine living with that every day and having that just grind you down.”

Unfortunately we can’t yet monitor what is happening across the globe on Facebook. But if the United States is any indication, we certainly can’t rely on Facebook’s self-reported data to tell the full story of what is happening on its platform.

As always, we will continue to do the hard work of holding Big Tech accountable.

Thanks for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup