Hello, friends,

If you’ve ever shopped for a product on Amazon, you might have noticed that Amazon Basics and other house brands and products exclusive to the site often pop up at the top of your search results.

Congress noticed, too. Last year, when congressional antitrust investigators were probing Amazon’s alleged abuses of its monopoly power, they asked the company to respond in writing to some key questions.

One question was: “Does Amazon’s algorithm take into account whether a product is a private label sold by Amazon?”

Amazon replied, in a written response, that its algorithm “did not take into account the factors described … when ranking shopping results.”

At The Markup, we wondered if that was true. It certainly didn’t jibe with what Amazon sellers have been saying publicly—that they couldn’t get their products to rank high in search results if an Amazon brand made a competing item. So, in typical Markup fashion, we decided to test Amazon’s claim.

Investigative reporter Adrianne Jeffries and investigative data journalist Leon Yin spent a year researching, conducting interviews, collecting thousands of Amazon search results, running the numbers and analyzing the results. Their definitive investigation was published this week: “Amazon Puts Its Own ‘Brands’ First Above Better Rated Products.”

They found that Amazon routinely ranked its own brands and exclusives ahead of better-known brands with higher star ratings and a greater number of reviews. For instance, shoppers searching for “cereal” would see Amazon’s Happy Belly Cinnamon Crunch cereal, with four stars and 1,010 reviews, in the number one spot, ahead of cereals with better and more reviews, including Cap’n Crunch (five stars, 14,069 reviews), Honey Bunches of Oats (five stars, 5,205 reviews), and Honey Nut Cheerios (five stars, 11,702 reviews). It was even ahead of the O.G., Cinnamon Toast Crunch, which also had better star ratings and more reviews.

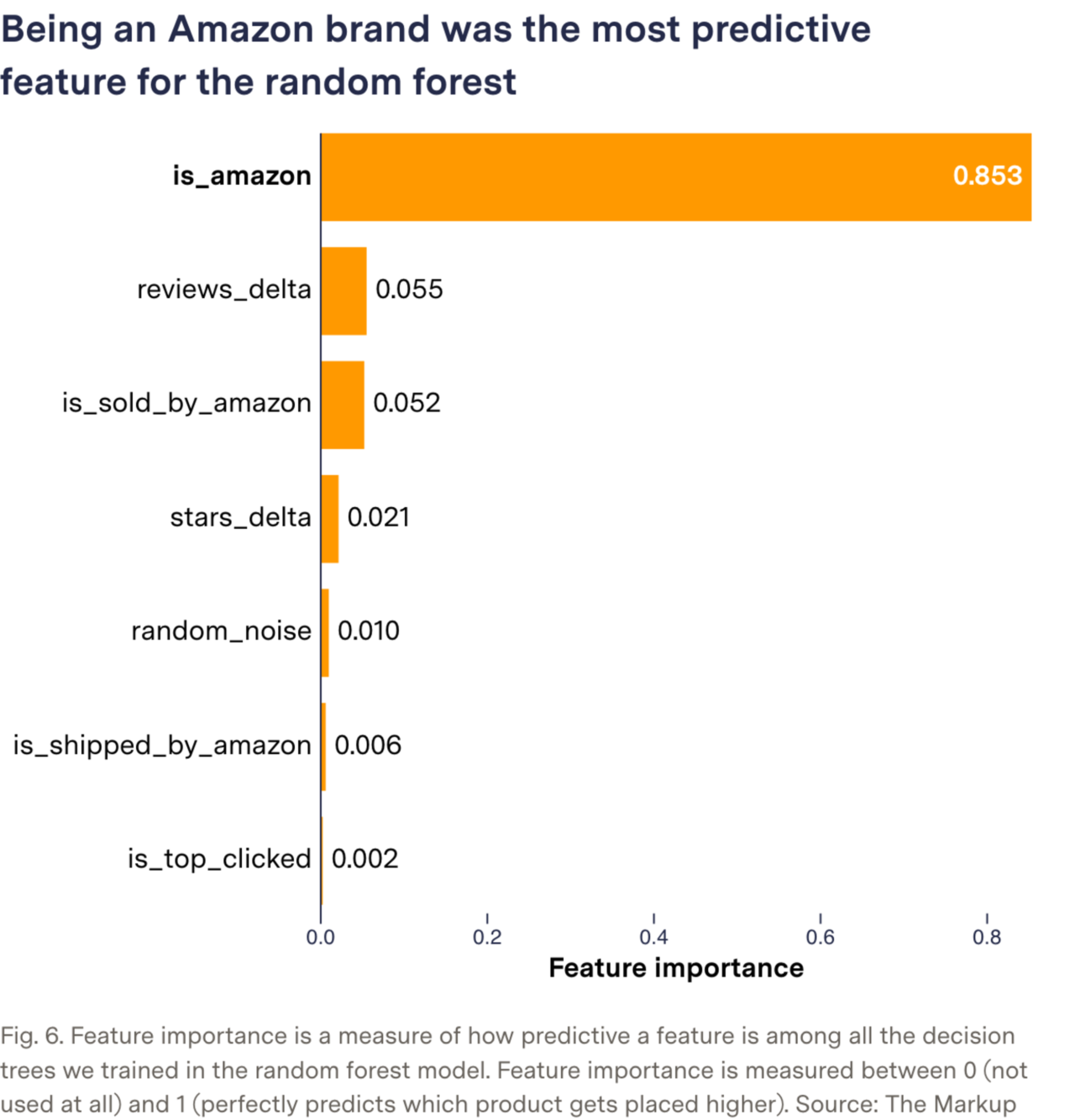

To determine what it took to get the top ranking in Amazon search results, our reporters used a machine learning model called random forest to run thousands of computer simulations that built a prediction model. Then we ran the numbers again and again in what is called an ablation study to evaluate the relative importance of the features of the model.

This provided answers to the three following questions:

What is the most important factor for predicting the top result of an Amazon search?

What is the only factor you need to make the prediction model perform well?

What is missing that makes the model do the worst?

The answer to all three questions was the same. Being an Amazon brand or exclusive was the most important factor for predicting the top result of an Amazon search. Being an Amazon brand or exclusive was the only factor needed to make the model perform well. And when information about whether a product is an Amazon brand or exclusive was missing, the model performed the worst.

Other factors like how many star ratings and number of reviews each product had were not even close runner-ups in predicting the top search results. We were not able to measure all possible factors, such as price and bestseller rank. (You can read all the gory technical details in our 30-page methodology)

In other words, the math said that, regardless of what Amazon told Congress, its algorithm appeared to be using Amazon brands and exclusives as an incredibly important factor in search result rankings.

When we presented our findings—including data, code, and methodology—Amazon spokesperson Nell Rona did not take issue with our analysis. Rather, she said that the products displayed in search results from Amazon brands and exlusives were “merchandising placements” and were not “search results.” She also said they were not ads, which under federal law have to be labeled as such.

So there you have it, the math that finally explains all the anecdotes that have piled up over the years: the sellers who complained that Amazon copied their products and pushed them down in rankings; the documents uncovered by Reuters and reported on this week showing that Amazon was boosting its own brand Solimo in search results in India; the Amazon executives who told Brad Stone, in his book Amazon Unbound, that they used “search seeding” to boost their private label brands in the early days.

The problem with anecdotal evidence, as in these stories, is that the human brain always has legitimate doubts. Are these stories representative? Could these sellers have done something to change the outcome? Were the practices described by former executives and documents just outliers?

The numbers confirm that the problem was systemic. It tells us that the deck was stacked against these sellers no matter what they did. When we ran our thousands of computer simulations, we found that there were very few scenarios that would allow a brand competing with Amazon to get to the top of search results.

To me, this is the power of our data-driven and statistically minded newsroom. We can flip the narrative: We are using powerful computational tools on behalf of the public, rather than on behalf of profits.

I sincerely hope that investigations like ours help to usher in an era of more statistical analyses that can reveal the ways that giants like Amazon are systematically using their power to further advantage themselves.

As always, thanks for reading.

Best

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup