Hello, friends,

Nearly six months ago, when California voters approved the strongest privacy law in the nation, it seemed like a win for people seeking control over their personal data.

The law, passed by a ballot initiative, requires companies to participate in a “global opt out”—meaning that people can click once to opt out of the sale or use of their personal data for advertising. The law also allows consumers to sue companies for violations of the laws’ security requirements and creates the California Privacy Protection Agency to take action against violators.

Former Democratic presidential primary candidate Andrew Yang declared that the law would likely usher in a new era of consumer privacy rights in the U.S., which is rare among wealthy nations in not having federal privacy standards. “It will sweep the country and I’m grateful to Californians for setting a new higher standard for how our data is treated,” Yang said at the time.

However, the law has actually swept in something else entirely: a wave of weaker privacy bills at the state level, pushed by Big Tech lobbying. As Todd Feathers reports for The Markup this week, more than a dozen states are considering privacy bills that we found are either directly supported by Big Tech or include the same tech-friendly provisions.

Many of these bills are modeled after a new Virginia law that is based on language crafted by Amazon and with input from Microsoft, according to reporting in Protocol, a tech news outlet. The Virginia law exempts many companies, even large ones, makes it harder to opt out, and does not allow consumers to sue.

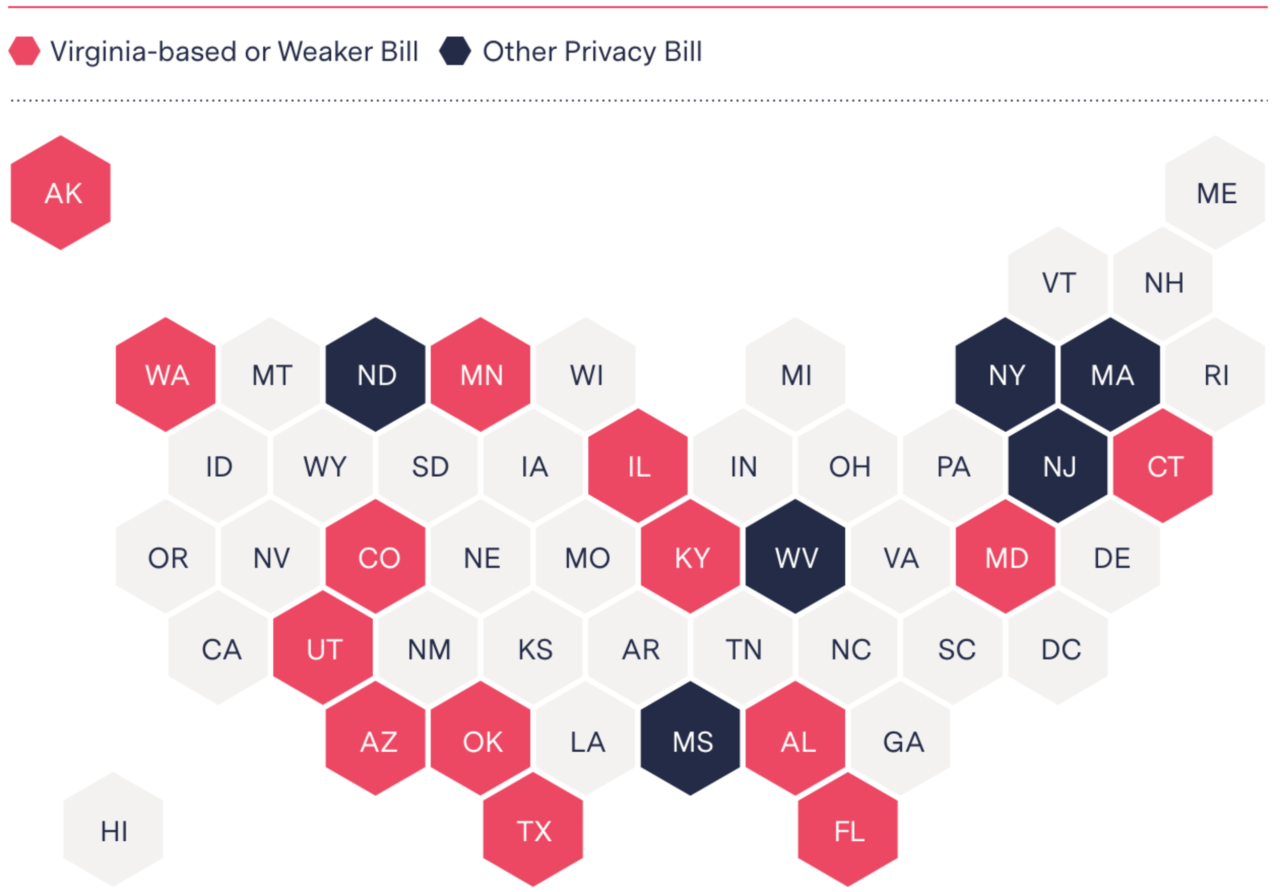

Todd found that 14 of the 20 state privacy bills under consideration around the country were built upon the same industry-backed framework as Virginia’s, or were weaker.

Fourteen of 20 proposed state privacy bills were built upon the same industry-backed framework as Virginia’s, or weaker

States with proposals for privacy bills, by type

Even more disturbing, Todd found that state lawmakers who tried to pass stronger privacy laws faced an unbeatable army of tech lobbyists.

Consider the fate of Connecticut state Senate majority leader Bob Duff, who introduced a privacy bill in 2020 that contained a private right of action—which the tech industry vehemently opposes.

During the bill’s public hearing last year, Duff said he looked out on a room “literally filled with every single lobbyist I’ve ever known in Hartford, hired by companies to defeat the bill.” The bill died once last year, and again this year. Duff finally gave up on stronger provisions and is now supporting a version of the Virginia legislation.

“It’s an uphill battle because you’re fighting a lot of forces on many fronts,” Duff told Todd. “They’re well funded, they’re well heeled, and they just hire a lot of lobbyists to defeat legislation for the simple reason that there’s a lot of money in online data.”

The sad thing is that it doesn’t cost much, apparently, to buy out all the lobbyists in a state capital. Connecticut records show that the Big Five Tech companies collectively spent around $600,000 lobbying in Connecticut in the past couple years—which is a tiny amount compared to their massive budgets.

Totals spent on lobbying in Connecticut (Jan. 1, 2019–March 31, 2021

Aggressive lobbying from tech companies has also blocked stronger privacy bills in other states, including North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Florida, Todd found.

The way things are going now, it seems likely that by the end of this year the U.S. will have a patchwork of state privacy laws—many of them weaker than California’s law. A competing set of privacy standards could prod Congress to pass one of the many comprehensive privacy legislation proposals that are likely to be introduced this year.

Many Big Tech companies have been supportive of the idea of a federal privacy law, even as they differ or have been vague (looking at you, Facebook) on the details of what it should be.

But if the state-by-state fight is any indication, the future could well look a lot like the present: a world where your data is collected indiscriminately, and it’s up to you to hunt around and try to find a setting somewhere that opts you out. And of course, that opt-out will likely only turn off targeted ads but won’t stop your data from being collected.

At The Markup, we take a different approach. We don’t think we need much data about users in order to serve them. As regular readers of this newsletter know, we go to great lengths—and pay what we call a Privacy Tax—to protect our readers’ from indiscriminate data tracking.

We’ll keep tracking the state of privacy laws and giving you tools like Blacklight to let you evaluate privacy risks for yourself.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Best,

Julia Angwin

Editor-in-Chief

The Markup